GENEVA — Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has triggered “the most massive violations of human rights” in the world today, the head of the United Nations said Monday, as the war pushed into its second year with no end in sight and tens of thousands dead.

Evgeniy Maloletka, Associated Press

Ukrainian servicemen who were wounded on the battlefield wait to leave the field hospital Sunday near Bakhmut, Ukraine.

The Russian invasion “has unleashed widespread death, destruction and displacement,” U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres said in a speech to the U.N.-backed Human Rights Council in Geneva.

After failing to capture Kyiv in the opening weeks of the invasion on Feb. 24 last year and suffering a series of humiliating setbacks during the fall, Russia has stabilized the front and is concentrating its efforts on capturing four provinces that Moscow illegally annexed in September — Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, and Zaporizhzhia. Ukraine, meanwhile, hopes to use battle tanks and other new weapons pledged by the West to launch new counteroffensives and reclaim more of the occupied territory.

Guterres said “attacks on civilians and civilian infrastructure have caused many casualties and terrible suffering.”

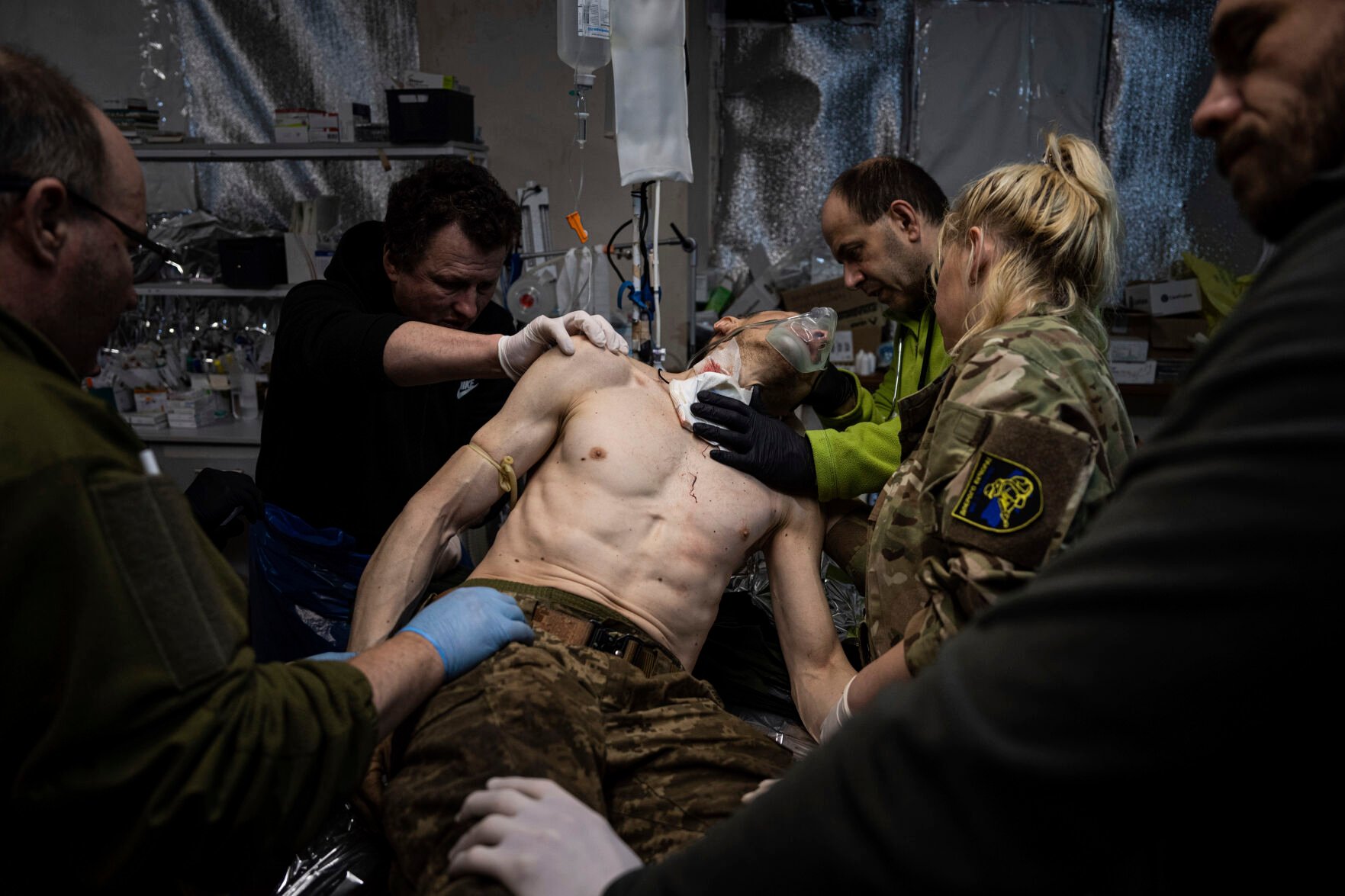

The intense fighting for territory in eastern Ukraine was in sharp focus Sunday at a Ukrainian field hospital treating wounded from the intense battle for the city of Bakhmut, which is devastated. A constant flow of battered and exhausted soldiers came in on stretchers.

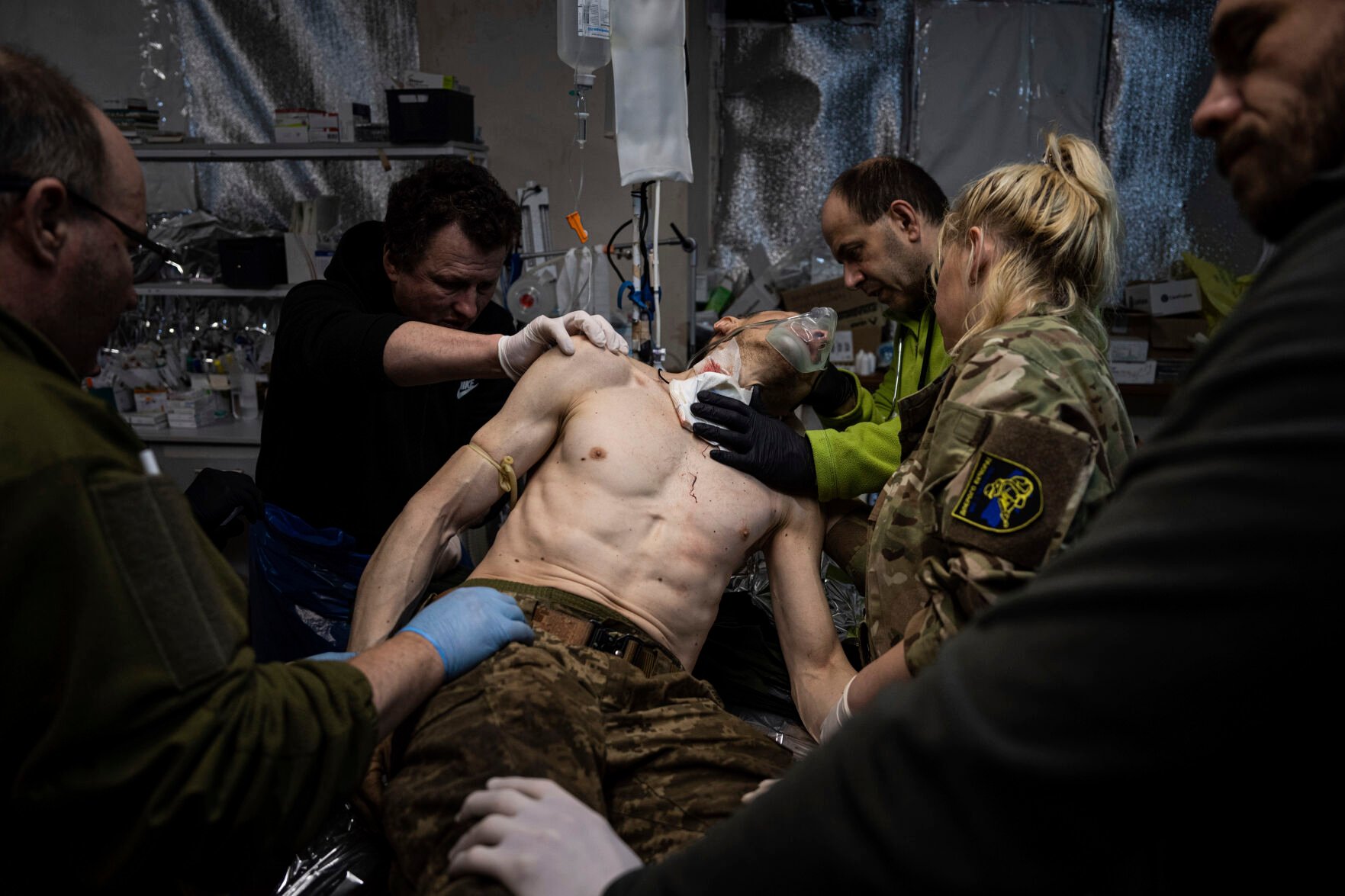

Evgeniy Maloletka, Associated Press

Ukrainian military medics treat their wounded comrade at the field hospital Sunday near Bakhmut, Ukraine.

Anatoliy, the chief of the medical service, said his team treats dozens of soldiers every day and barely has time to eat.

“My medics work practically non-stop. Before the full-scale invasion we had 50-60 wounded in a nine-month rotation, and now sometimes we have more (than that) in one day,” he told The Associated Press. He provided only one name for security reasons.

Evgeniy Maloletka, Associated Press

Ukrainian military medics treat their wounded comrade at the field hospital Sunday near Bakhmut, Ukraine.

Guterres’ remarks came as the Ukrainian military said that Russia launched attacks with exploding drones on several regions of the country from late Sunday until Monday morning, killing two people.

Meanwhile, Belarusian opposition activists claimed a military air base outside Belarusia’s capital that hosts Russian warplanes came under attack Sunday by Belarusian guerrillas.

BYPOL, an online messaging app channel run by the activists, and several other online resources operated by the Belarusian opposition, said an A-50 early warning and control aircraft was seriously damaged in the attack at the Machulishchy base near Minsk.

The activists provided no evidence to support the claims, which couldn’t be independently verified. Belarusian and Russian officials made no comment, but Belarusia’s President Alexander Lukashenko urged top military and security officials on Monday to tighten discipline.

Russia used the territory of its ally Belarus to invade Ukraine a year ago. Belarus continues to host Russian troops, warplanes and other weapons.

Guterres, in his Geneva speech, cited cases of sexual violence, enforced disappearances, arbitrary detention and violations of the rights of prisoners of war documented by the U.N. human rights office.

He decried how the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, now 75 years old, has been “too often misused and abused.”

“It is exploited for political gain and it is ignored, often, by the very same people,” Guterres said. “Some governments chip away at it. Others use a wrecking ball.”

“This is a moment to stand on the right side of history,” he told the council, the U.N.’s top human rights body. Russia withdrew from its seat last year amid a surge in international pressure over the war in Ukraine.

Dozens of high-level envoys at the Geneva meeting — many from Western countries — lashed out at Russia over its conduct of the war. At the simultaneous Conference on Disarmament, another U.N.-backed body, delegates criticized Putin’s decision to suspend Russia’s participation in the New START agreement with the United States, the last nuclear arms control agreement between Moscow and Washington.

Russia was not represented at the council, and its top envoy to the session wasn’t expected to speak until Thursday.

Russian officials have shown little sign they may be reconsidering their attack on their neighbor, however.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said Monday: “We aren’t seeing any conditions for a peaceful settlement now.”

Dmitry Medvedev, the deputy head of Russia’s Security Council that is chaired by President Vladimir Putin, went a step further, once again raising the specter of nuclear war and a nightmare outcome to Europe’s biggest and deadliest conflict since World War II.

He chided the U.S. and its allies for providing Ukraine with military and other support to help push back the Kremlin’s forces. Their longer-term aim, he claimed, is to break up Russia.

Putin has also framed the war in those terms, saying it’s an existential risk to Russia.

In the Sunday-Monday attacks, Ukraine’s General Staff said Kyiv’s forces shot down 11 out of 14 Iranian-made Shahed drones.

Ukraine’s presidential office said Monday that at least two civilians were killed and nine others wounded by Russian attacks over the previous 24 hours.

It said intense fighting has continued around Bakhmut, Avdiivka and Vuhledar in the Donetsk region, which have come under relentless Russian shelling.

Ukrainian military analyst Oleh Zhdanov said the Russian offensive aimed at securing control of eastern Ukraine has effectively become bogged down while losing “huge numbers of weapons and ammunition.”

HOGP

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, left, and U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen shake hands during their meeting in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, Feb. 27, 2023. (Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP)

Meanwhile, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said Monday her first visit to Ukraine underscored Washington’s commitment to continuing its economic support for the country, as the din of air raid sirens echoed across the Ukrainian capital.

Yellen said following talks with Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal that the US has provided nearly $50 billion in security, economic and humanitarian assistance and announced another multibillion dollar package to boost the country’s economy.

Shmyhal offered thanks to the U.S. for its support and hailed Yellen as a “friend of Ukraine.”

-

Here are 5 ways the war in Ukraine has changed the world

Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP, File

Three months before the invasion, then-British Prime Minister Boris Johnson scoffed at suggestions that the British army needed more heavy weapons. “The old concepts of fighting big tank battles on European landmass,” he said, “are over.”

Johnson is now urging the U.K. to send more battle tanks to help Ukraine repel Russian forces.

Despite the role played by new technology such as satellites and drones, this 21st-century conflict in many ways resembles one from the 20th. Fighting in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region is a brutal slog, with mud, trenches and bloody infantry assaults reminiscent of World War I.

The conflict has sparked a new arms race that reminds some analysts of the 1930s buildup to World War II. Russia has mobilized hundreds of thousands of conscripts and aims to expand its military from 1 million to 1.5 million troops. The U.S. has ramped up weapons production to replace the stockpiles shipped to Ukraine. France plans to boost military spending by a third by 2030, while Germany has abandoned its longstanding ban on sending weapons to conflict zones and shipped missiles and tanks to Ukraine.

Before the war, many observers assumed that military forces would move toward more advanced technology and cyber warfare and become less reliant on tanks or artillery, said Patrick Bury, senior lecturer in security at the University of Bath.

But in Ukraine, guns and ammunition are the most important weapons.

"It is, for the moment at least, being shown that in Ukraine, conventional warfare — state-on-state — is back,” Bury said.

Ukrainian Presidential Press Office via AP, File

Three months before the invasion, then-British Prime Minister Boris Johnson scoffed at suggestions that the British army needed more heavy weapons. “The old concepts of fighting big tank battles on European landmass,” he said, “are over.”

Johnson is now urging the U.K. to send more battle tanks to help Ukraine repel Russian forces.

Despite the role played by new technology such as satellites and drones, this 21st-century conflict in many ways resembles one from the 20th. Fighting in eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region is a brutal slog, with mud, trenches and bloody infantry assaults reminiscent of World War I.

The conflict has sparked a new arms race that reminds some analysts of the 1930s buildup to World War II. Russia has mobilized hundreds of thousands of conscripts and aims to expand its military from 1 million to 1.5 million troops. The U.S. has ramped up weapons production to replace the stockpiles shipped to Ukraine. France plans to boost military spending by a third by 2030, while Germany has abandoned its longstanding ban on sending weapons to conflict zones and shipped missiles and tanks to Ukraine.

Before the war, many observers assumed that military forces would move toward more advanced technology and cyber warfare and become less reliant on tanks or artillery, said Patrick Bury, senior lecturer in security at the University of Bath.

But in Ukraine, guns and ammunition are the most important weapons.

"It is, for the moment at least, being shown that in Ukraine, conventional warfare — state-on-state — is back,” Bury said.

-

Here are 5 ways the war in Ukraine has changed the world

AP Photo/Markus Schreiber, File

Russian President Vladimir Putin hoped the invasion would split the West and weaken NATO. Instead, the military alliance has been reinvigorated. A group set up to counter the Soviet Union has a renewed sense of purpose and two new aspiring members in Finland and Sweden, which ditched decades of nonalignment and asked to join NATO as protection against Russia.

The 27-nation European Union has hit Russia with tough sanctions and sent Ukraine billions in support. The war put Brexit squabbles into perspective, thawing diplomatic relations between the bloc and awkward former member Britain.

“The EU is taking sanctions, quite serious sanctions, in the way that it should. The U.S. is back in Europe with a vengeance in a way we never thought it would be again,” said defense analyst Michael Clarke, former head of the Royal United Services Institute think tank.

NATO member states have poured weapons and equipment worth billions of dollars into Ukraine. The alliance has buttressed its eastern flank, and the countries nearest to Ukraine and Russia, including Poland and the Baltic states, have persuaded more hesitant NATO and European Union allies, potentially shifting Europe’s center of power eastwards.

There are some cracks in the unity. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Putin’s closest ally in the EU, has lobbied against sanctions on Moscow, refused to send weapons to Ukraine and held up an aid package from the bloc for Kyiv.

Western unity will come under more and more pressure the longer the conflict grinds on.

“Russia is planning for a long war,” NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said at the end of 2022, but the alliance was also ready for the “long haul.”

AP Photo/Markus Schreiber, File

Russian President Vladimir Putin hoped the invasion would split the West and weaken NATO. Instead, the military alliance has been reinvigorated. A group set up to counter the Soviet Union has a renewed sense of purpose and two new aspiring members in Finland and Sweden, which ditched decades of nonalignment and asked to join NATO as protection against Russia.

The 27-nation European Union has hit Russia with tough sanctions and sent Ukraine billions in support. The war put Brexit squabbles into perspective, thawing diplomatic relations between the bloc and awkward former member Britain.

“The EU is taking sanctions, quite serious sanctions, in the way that it should. The U.S. is back in Europe with a vengeance in a way we never thought it would be again,” said defense analyst Michael Clarke, former head of the Royal United Services Institute think tank.

NATO member states have poured weapons and equipment worth billions of dollars into Ukraine. The alliance has buttressed its eastern flank, and the countries nearest to Ukraine and Russia, including Poland and the Baltic states, have persuaded more hesitant NATO and European Union allies, potentially shifting Europe’s center of power eastwards.

There are some cracks in the unity. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, Putin’s closest ally in the EU, has lobbied against sanctions on Moscow, refused to send weapons to Ukraine and held up an aid package from the bloc for Kyiv.

Western unity will come under more and more pressure the longer the conflict grinds on.

“Russia is planning for a long war,” NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said at the end of 2022, but the alliance was also ready for the “long haul.”

-

-

Here are 5 ways the war in Ukraine has changed the world

Mikhail Klimentyev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP, File

The war has made Russia a pariah in the West. Its oligarchs have been sanctioned and its businesses blacklisted, and international brands including McDonald's and Ikea have disappeared from the country’s streets.

Yet Moscow is not entirely friendless. Russia has strengthened economic ties with China, though Beijing is keeping its distance from the fighting and so far has not sent weapons. The U.S. has recently expressed concern that may change.

China is closely watching a conflict that may serve as either encouragement or warning to Beijing about any attempt to reclaim self-governing Taiwan by force.

Putin has reinforced military links with international outcasts North Korea and Iran, which supplies armed drones that Russia unleashes on Ukrainian infrastructure. Moscow continues to build influence in Africa and the Middle East with its economic and military clout. Russia’s Wagner mercenary group has grown more powerful in conflicts from the Donbas to the Sahel.

In an echo of the Cold War, the world is divided into two camps, with many countries, including densely populated India, hedging their bets to see who emerges on top.

Tracey German, professor of conflict and security at King’s College London, said the conflict has widened a rift between the “U.S.-led liberal international order” on one side, and angry Russia and emboldened rising superpower China on the other.

Mikhail Klimentyev, Sputnik, Kremlin Pool Photo via AP, File

The war has made Russia a pariah in the West. Its oligarchs have been sanctioned and its businesses blacklisted, and international brands including McDonald's and Ikea have disappeared from the country’s streets.

Yet Moscow is not entirely friendless. Russia has strengthened economic ties with China, though Beijing is keeping its distance from the fighting and so far has not sent weapons. The U.S. has recently expressed concern that may change.

China is closely watching a conflict that may serve as either encouragement or warning to Beijing about any attempt to reclaim self-governing Taiwan by force.

Putin has reinforced military links with international outcasts North Korea and Iran, which supplies armed drones that Russia unleashes on Ukrainian infrastructure. Moscow continues to build influence in Africa and the Middle East with its economic and military clout. Russia’s Wagner mercenary group has grown more powerful in conflicts from the Donbas to the Sahel.

In an echo of the Cold War, the world is divided into two camps, with many countries, including densely populated India, hedging their bets to see who emerges on top.

Tracey German, professor of conflict and security at King’s College London, said the conflict has widened a rift between the “U.S.-led liberal international order” on one side, and angry Russia and emboldened rising superpower China on the other.

-

Here are 5 ways the war in Ukraine has changed the world

AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File

The war’s economic impact has been felt from chilly homes in Europe to food markets in Africa.

Before the war, European Union nations imported almost half their natural gas and third of their oil from Russia. The invasion, and sanctions slapped on Russia in response, delivered an energy price shock on a scale not seen since the 1970s.

The war disrupted global trade that was still recovering from the pandemic. Food prices have soared, since Russia and Ukraine are major suppliers of wheat and sunflower oil, and Russia is the world’s top fertilizer producer.

Grain-carrying ships have continued to sail from Ukraine under a fragile U.N.-brokered deal, and prices have come down from record levels. But food remains a geopolitical football. Russia has sought to blame the West for high prices, while Ukraine and its allies accuse Russia of cynically using hunger as a weapon.

The war "has really highlighted the fragility” of an interconnected world, just as the pandemic did, German said, and the full economic impact has yet to be felt.

The war also roiled attempts to fight climate change, driving an upsurge in Europe’s use of heavily polluting coal. Yet Europe’s rush away from Russian oil and gas may speed the transition to renewable energy sources faster than countless warnings about the dangers of global warming. The International Energy Agency says the world will add as much renewable power in the next five years as it did in the last 20.

AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File

The war’s economic impact has been felt from chilly homes in Europe to food markets in Africa.

Before the war, European Union nations imported almost half their natural gas and third of their oil from Russia. The invasion, and sanctions slapped on Russia in response, delivered an energy price shock on a scale not seen since the 1970s.

The war disrupted global trade that was still recovering from the pandemic. Food prices have soared, since Russia and Ukraine are major suppliers of wheat and sunflower oil, and Russia is the world’s top fertilizer producer.

Grain-carrying ships have continued to sail from Ukraine under a fragile U.N.-brokered deal, and prices have come down from record levels. But food remains a geopolitical football. Russia has sought to blame the West for high prices, while Ukraine and its allies accuse Russia of cynically using hunger as a weapon.

The war "has really highlighted the fragility” of an interconnected world, just as the pandemic did, German said, and the full economic impact has yet to be felt.

The war also roiled attempts to fight climate change, driving an upsurge in Europe’s use of heavily polluting coal. Yet Europe’s rush away from Russian oil and gas may speed the transition to renewable energy sources faster than countless warnings about the dangers of global warming. The International Energy Agency says the world will add as much renewable power in the next five years as it did in the last 20.

-

-

Here are 5 ways the war in Ukraine has changed the world

AP Photo/Visar Kryeziu, File

The conflict is a stark reminder that individuals have little control over the course of history. No one knows that better than the 8 million Ukrainians who have been forced to flee homes and country for new lives in communities across Europe and beyond.

For millions of people less directly affected, the sudden shattering of Europe’s peace has brought uncertainty and anxiety.

Putin’s veiled threats to use atomic weapons if the conflict escalates revived fears of nuclear war that had lain dormant since the Cold War. Fighting has raged around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, raising the specter of a new Chernobyl.

Patricia Lewis, director of the international security program at think-tank Chatham House, said Putin's nuclear saber-rattling had provoked “more anger than fear” in the West. But concerns about nuclear escalation were heightened by Putin's Feb. 21 announcement that he was suspending Russia's participation in its sole remaining nuclear arms control treaty with the U.S.

Putin stopped short of withdrawing completely from the New START treaty and said Moscow would respect the treaty’s caps on nuclear weapons, keeping a faint glimmer of arms control alive.

AP Photo/Visar Kryeziu, File

The conflict is a stark reminder that individuals have little control over the course of history. No one knows that better than the 8 million Ukrainians who have been forced to flee homes and country for new lives in communities across Europe and beyond.

For millions of people less directly affected, the sudden shattering of Europe’s peace has brought uncertainty and anxiety.

Putin’s veiled threats to use atomic weapons if the conflict escalates revived fears of nuclear war that had lain dormant since the Cold War. Fighting has raged around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, raising the specter of a new Chernobyl.

Patricia Lewis, director of the international security program at think-tank Chatham House, said Putin's nuclear saber-rattling had provoked “more anger than fear” in the West. But concerns about nuclear escalation were heightened by Putin's Feb. 21 announcement that he was suspending Russia's participation in its sole remaining nuclear arms control treaty with the U.S.

Putin stopped short of withdrawing completely from the New START treaty and said Moscow would respect the treaty’s caps on nuclear weapons, keeping a faint glimmer of arms control alive.