In El Salvador, transgender community struggles for rights and survival

SAN SALVADOR, El Salvador — Fabricio Chicas knows exactly what will happen. As soon as he hands in his ID, the employee on the other side of the counter will look at him with suspicion, asking why he carries a document that identifies him as female.

Whether at a bank, a hospital or a human resources office, the 49-year-old Salvadoran provides the same answer: I am a transgender man who has not been able to change his name and gender on his ID.

Salvador Melendez, Associated Press

Fabricio Chicas, a transgender man, right, poses for a photo with his partner Elizabeth Lopez, and their pets, at their home in San Salvador, El Salvador, on April 30. Even though the country’s Supreme Court in 2022 determined that the inability of a person to change their name because of gender identity constitutes discriminatory treatment, the 49-year-old has not been able to change his name from Patricia to Fabricio, nor his gender on his ID, a fate shared by many transgender people in El Salvador.

His fate is shared by many transgender people in El Salvador, where Catholicism and evangelicalism are prevalent, abortion is banned and the legalization of same-sex marriage seems unlikely.

In 2022, the country’s Supreme Court determined that the inability of a person to change their name because of gender identity constitutes discriminatory treatment. A ruling ordered the National Assembly to issue a reform that facilitates the process, but the deadline expired three months ago, and the lawmakers did not comply.

“It is part of a much broader pattern of weakening the rule of law and judicial independence,” said Cristian González Cabrera, LGBTQ rights researcher at Human Rights Watch.

‘I was so depressed I didn’t want to live’

When he was little, Chicas’ mother agreed to dress him in masculine clothes and called him “my boy.” Everything changed when he turned 9.

“I was abused, and my mom started to overprotect me,” he said.

Salvador Melendez, Associated Press

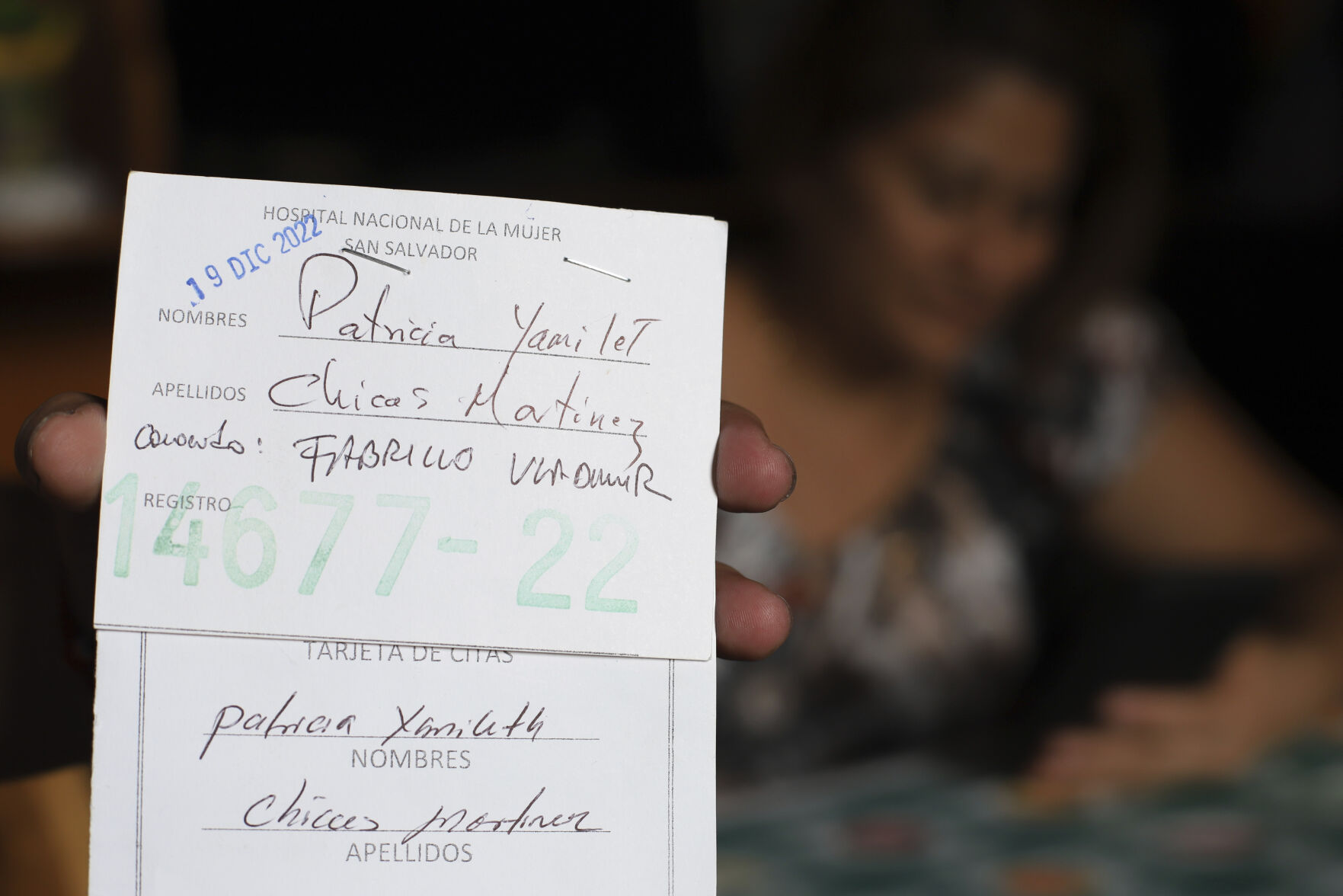

Transgender man Fabricio Chicas holds his Women’s National Hospital user card, filled out with his given name, Patricia Yamileth Chicas Martinez, during an interview in his home in San Salvador, El Salvador, on April 30. In hospitals, Chicas said, nurses have made fun of him. Since Chicas still requires gynecological consultations, health personnel often call him by the female name on his ID or have delayed his appointments, claiming that they cannot treat “people like him.”

Perhaps feeling that treating Chicas as a boy exposed him to harm, she dressed him again in girl’s clothing. “I was so depressed I didn’t want to live,” he recalled.

When he turned 15, he met a transgender man who advised him to start his physical transformation. The man suggested pressing his breasts with an iron to prevent them from growing.

Chicas ended up in the hospital, with an infection produced by hematomas, and his mother made him swear he would never alter his body to look like a man.

Though he said yes, he promised something to himself: I’ll grow up, find a job and leave.

Early in a transition, lack of support from one’s own family is often the biggest challenge, said Mónica Linares.

The 43-year-old transgender woman left home when she turned 14 and started her transition. She currently works as an activist at the organization ASPIDH Arcoiris Trans.

“It hasn’t been easy, but when you really have an identity and you want to defend what you really want, you are willing to lose everything,” Linares said.

Salvador Melendez, Associated Press

Monica Linares, an activist for the ASPIDH Arcoiris Trans organization, and others, gather for a protest to demand the approval of a Gender Identity Law, in San Salvador, El Salvador, on May 17. The 43-year-old transgender woman left home when she turned 14 and immediately started her transition.

For more than 15 years, she was a sex worker. She lost friends to transphobic killings and saw others migrate because of gangs.

In her current job is she collaborates with other organizations to support LGBT rights, especially to put pressure on lawmakers who show little interest in reviewing a gender identity bill that was presented in 2021.

The bill would comply with the Supreme Court’s ruling from 2022 and go a step further, allowing trans people to change not only their names but also their gender on official paperwork.

Insurmountable red tape

The lack of IDs that are consistent with the gender identity of trans Salvadoreans can make their daily life troublesome.

Some employees of internet companies refuse to solve complaints made by phone, alleging that the voice of the person issuing the complaint does not match the gender they have on file.

Insurers don’t allow trans people to register their partners as beneficiaries in the event of death, since their guidelines state that couples must consist of a man and a woman.

Salvador Melendez, Associated Press

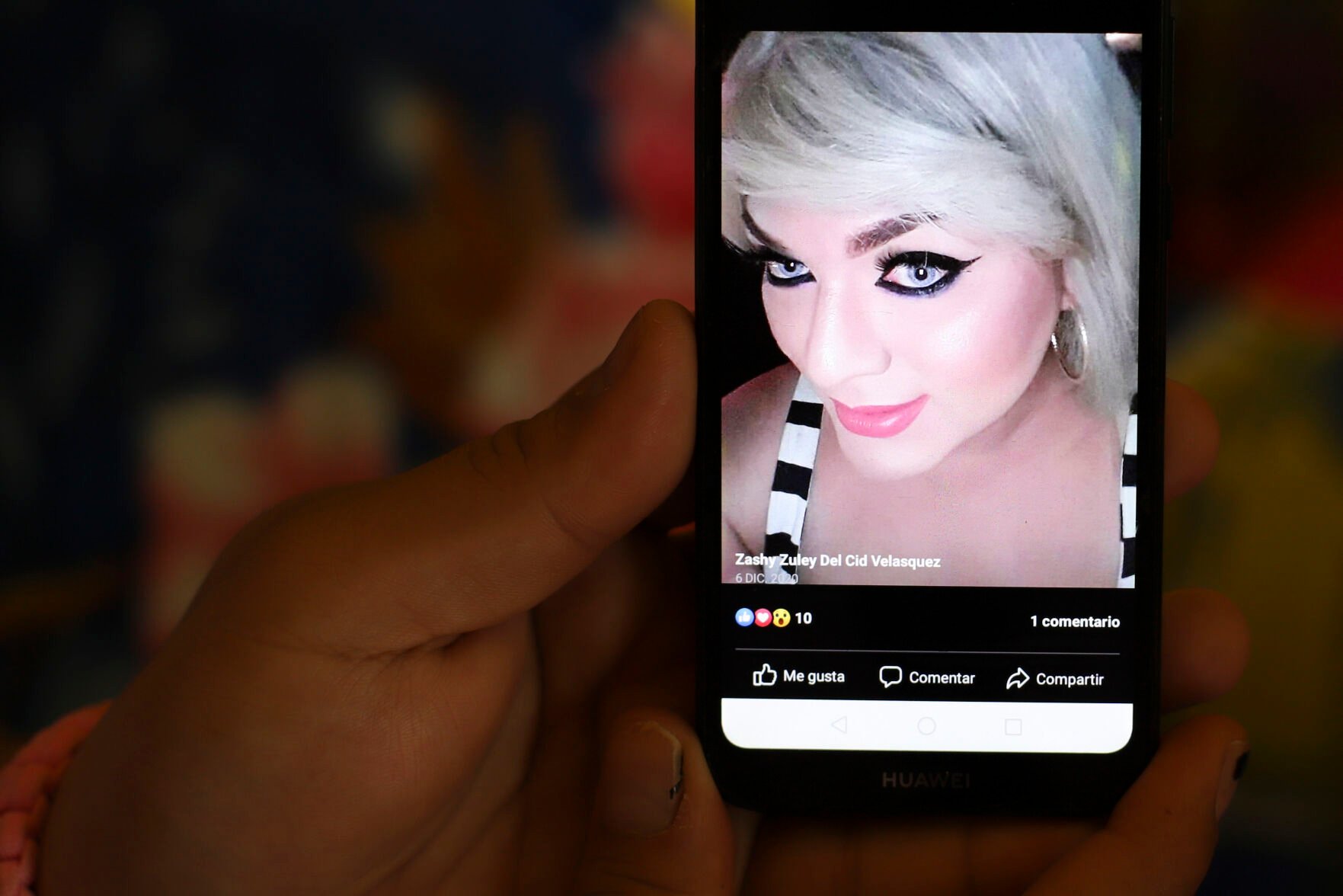

A friend shows a digital picture of Zashy Zuley del Cid Velasquez, a 27-year-old transgender woman shot in the back walking alone on an April night, in San Miguel, El Salvador, on May 25. Violence against trans women in the country has increased in the last two years, said Rina Montti, director of investigations at the human rights organization Cristosal.

Chicas has had problems collecting remittances, banks have denied him loans, and employers have not hired him because his applications reveal that he is a transgender man.

In hospitals, he said, health personnel have delayed his appointments, claiming that they cannot treat “people like him.”

In this deeply religious country, discrimination against transgender people goes beyond paperwork.

A report by Human Rights Watch and COMCAVIS TRANS in 2022 details how transgender people in El Salvador suffer violence and discrimination.

“Security forces, gangs, and victims’ families and communities are perpetrators; harm occurs in public spaces, homes, schools, and places of worship,” the report states.

Latin American countries such as Chile, Argentina, Cuba, Colombia and Mexico have issued laws that protect some rights of the LGBTQ community and allow transgender people to modify their official documents to match their gender identity. In El Salvador, though, since President Nayib Bukele came into power in 2019, there have been setbacks.

Among other actions, the government dissolved the Ministry for Social Inclusion, which investigated LGBTQ issues nationwide, and it restructured an educational institute for addressing sexual orientation in schools.

Bukele has said that he will never legalize same-sex marriage and the Catholic Church has backed his position. The archdiocese’s office did not respond to multiple requests from The Associated Press for comment.

Family ties go beyond blood

In the backyard of Chicas’ house, Pongo and Polar Bear wave their tails. Behind the dogs comes Elizabeth López, Chicas’ partner for the past seven years. They met soon after Chicas’ mother died, when he decided to use hormones and start his transition.

At first, López seems distrustful. Too many strangers have hurt them beyond words.

She remembers a guard who ordered them to leave a public pool after Chicas said he was unable to remove his shirt, given that his physical transition was incomplete. They both recall the time when he had emergency surgery and health personnel forbid her to visit, alleging they were both “women,” so they could never marry or become a family.

Chicas disagrees. Family, he said, are not the ones who share blood; they are the ones who support each other.

The couple has been sharing their home with a young transgender man who left his own home. Chicas offers care and advice.

Recently, the young man came home accompanied by his girlfriend and approached Chicas to introduce them. He told his girlfriend: “Meet my old man.”

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthdariatorchukova // Shutterstock

Superficially, Americans and their legislators accept and understand LGBTQ+ individuals more now than even a decade ago. The Supreme Court's 2015 decision to legalize same-gender marriage stands as of the most tangible and significant wins for LGBTQ+ rights—yet the 2015 ruling only directly protected cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals.

At least 19 states in 2016 considered bathroom bills, legislation that would force every person to use the gendered restroom matching the gender listed on their birth certificate. North Carolina passed this legislation, igniting conversations across the country and empowering lawmakers to draft similar bills in other states. But sister bills struggled to pass, and even North Carolina has since repealed its bathroom bill.

Several congressional representatives have turned to gender legislation to target a new group: transgender youth.

Stacker took a look at state-by-state data on sexual orientation and gender identity policies that affect transgender youth from the Transgender Law Center.

All 50 states and Washington D.C. were then ranked by their total “policy tallies” (the number of laws and policies driving equality for LGBTQ+ people), with #51 being the most restrictive state and #1 being the most protective state of trans youth. Negative tallies mean more discrimination laws exist than protection laws.

TLC's policy tally accounts only for passed legislation and does not take into account activism efforts, attitudes, and feelings expressed by people in the state, nor implementations of these laws. The core categories TLC considered revolve around relationships and parental recognition, nondiscrimination, religious exemptions, LGBTQ+ youth, health care, criminal justice, and identity documents.

TLC's findings capture how trans youth remain protected or vulnerable by statutory law, but legislation is elastic and lawmakers introduce new bills constantly. One category of these rankings only capture laws pertaining to sexuality since significant overlap exists within the queer community and within the legislation. Many lesbian, gay, or bisexual individuals also identify as transgender, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming, meaning LGBTQ+ individuals can identify with more than one queer identity.

Since 2020, anti-trans youth legislation claiming to protect children popped up more frequently in state legislatures, entering the more mainstream lexicon in 2021. During the first three months of 2022, lawmakers filed about 240 anti-LGBTQ+ laws—most of which targeted trans people.

Tennessee, the top state for anti-trans youth legislation, in 2017 signed a bill into law preventing trans children from receiving gender-affirming care. It was the fifth anti-trans law to pass in the state. Bills like these claim to protect parents and children, yet lawmakers in Tennessee are also considering a bill that would establish common-law marriages in the state between “one man and one woman” while eliminating age restrictions for marriage.

While anti-trans youth legislation outnumbers legislation to protect trans youth, several states have enacted or are considering laws intended to protect trans children. California has gone so far as to introduce a bill to accept families escaping anti-trans youth legislation. Colorado—formerly known as the “Hate State” for its history of passing anti-LGBTQ+ legislation throughout the ’90s—passed legislation banning conversion therapy, prohibiting bullying based on LGBTQ+ identities, and ending discrimination against LGBTQ+ families adopting children. Hawaii passed legislation in March that would require health insurance companies to pay for gender-affirming care—but not until 2060.

You may also like: A history of LGBTQ+ representation in film

dariatorchukova // Shutterstock

dariatorchukova // ShutterstockSuperficially, Americans and their legislators accept and understand LGBTQ+ individuals more now than even a decade ago. The Supreme Court's 2015 decision to legalize same-gender marriage stands as of the most tangible and significant wins for LGBTQ+ rights—yet the 2015 ruling only directly protected cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals.

At least 19 states in 2016 considered bathroom bills, legislation that would force every person to use the gendered restroom matching the gender listed on their birth certificate. North Carolina passed this legislation, igniting conversations across the country and empowering lawmakers to draft similar bills in other states. But sister bills struggled to pass, and even North Carolina has since repealed its bathroom bill.

Several congressional representatives have turned to gender legislation to target a new group: transgender youth.

Stacker took a look at state-by-state data on sexual orientation and gender identity policies that affect transgender youth from the Transgender Law Center.

All 50 states and Washington D.C. were then ranked by their total “policy tallies” (the number of laws and policies driving equality for LGBTQ+ people), with #51 being the most restrictive state and #1 being the most protective state of trans youth. Negative tallies mean more discrimination laws exist than protection laws.

TLC's policy tally accounts only for passed legislation and does not take into account activism efforts, attitudes, and feelings expressed by people in the state, nor implementations of these laws. The core categories TLC considered revolve around relationships and parental recognition, nondiscrimination, religious exemptions, LGBTQ+ youth, health care, criminal justice, and identity documents.

TLC's findings capture how trans youth remain protected or vulnerable by statutory law, but legislation is elastic and lawmakers introduce new bills constantly. One category of these rankings only capture laws pertaining to sexuality since significant overlap exists within the queer community and within the legislation. Many lesbian, gay, or bisexual individuals also identify as transgender, nonbinary, or gender nonconforming, meaning LGBTQ+ individuals can identify with more than one queer identity.

Since 2020, anti-trans youth legislation claiming to protect children popped up more frequently in state legislatures, entering the more mainstream lexicon in 2021. During the first three months of 2022, lawmakers filed about 240 anti-LGBTQ+ laws—most of which targeted trans people.

Tennessee, the top state for anti-trans youth legislation, in 2017 signed a bill into law preventing trans children from receiving gender-affirming care. It was the fifth anti-trans law to pass in the state. Bills like these claim to protect parents and children, yet lawmakers in Tennessee are also considering a bill that would establish common-law marriages in the state between “one man and one woman” while eliminating age restrictions for marriage.

While anti-trans youth legislation outnumbers legislation to protect trans youth, several states have enacted or are considering laws intended to protect trans children. California has gone so far as to introduce a bill to accept families escaping anti-trans youth legislation. Colorado—formerly known as the “Hate State” for its history of passing anti-LGBTQ+ legislation throughout the ’90s—passed legislation banning conversion therapy, prohibiting bullying based on LGBTQ+ identities, and ending discrimination against LGBTQ+ families adopting children. Hawaii passed legislation in March that would require health insurance companies to pay for gender-affirming care—but not until 2060.

You may also like: A history of LGBTQ+ representation in film

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthMihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -6

- Gender identity policy tally: -5.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.25

Mihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -6

- Gender identity policy tally: -5.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.25

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthW. Scott McGill // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -5.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

W. Scott McGill // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -5.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthJoseph Sohm // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -4.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -4

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

Joseph Sohm // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -4.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -4

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthKristi Blokhin // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -4

- Gender identity policy tally: -3.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

Kristi Blokhin // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -4

- Gender identity policy tally: -3.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -3.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

You may also like: Do you know the mayors of these major cities?

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -3.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.5

You may also like: Do you know the mayors of these major cities?

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthJoseph Sohm // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -3

- Gender identity policy tally: -5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2

Joseph Sohm // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -3

- Gender identity policy tally: -5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -2.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -3.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 1

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -2.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -3.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 1

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthf11photo // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -0.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.5

f11photo // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -0.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthJon Bilous // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: -0.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -1.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 1

Jon Bilous // Shutterstock- Overall tally: -0.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -1.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 1

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthCrackerClips Stock Media // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 0.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -2.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.75

You may also like: ‘I have a dream’ and the rest of the greatest speeches of the 20th century

CrackerClips Stock Media // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 0.5

- Gender identity policy tally: -2.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.75

You may also like: ‘I have a dream’ and the rest of the greatest speeches of the 20th century

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 0.75

- Gender identity policy tally: -2.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.5

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 0.75

- Gender identity policy tally: -2.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 1.75

- Gender identity policy tally: -0.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.5

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 1.75

- Gender identity policy tally: -0.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthEQRoy // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 2.25

- Gender identity policy tally: -3.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.75

EQRoy // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 2.25

- Gender identity policy tally: -3.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.75

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 3.75

- Gender identity policy tally: -0.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.25

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 3.75

- Gender identity policy tally: -0.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.25

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthMihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 4

- Gender identity policy tally: -0.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.5

You may also like: Oldest national parks in America

Mihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 4

- Gender identity policy tally: -0.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.5

You may also like: Oldest national parks in America

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthJacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 4

- Gender identity policy tally: -1.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 4

- Gender identity policy tally: -1.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 4

- Gender identity policy tally: -1.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.5

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 4

- Gender identity policy tally: -1.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthvmfreire // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 5.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 2

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.75

vmfreire // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 5.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 2

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.75

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthZack Frank // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 5.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 1

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.75

Zack Frank // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 5.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 1

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.75

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 6.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 1.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25

You may also like: History of LGBTQ+ inclusion in the workforce

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 6.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 1.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25

You may also like: History of LGBTQ+ inclusion in the workforce

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 7.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.75

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 7.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.75

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthMihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 9.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 3.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6

Mihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 9.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 3.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSusan M Hall // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 10.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.25

Susan M Hall // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 10.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 3

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.25

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthJoseph Sohm // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 11.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 4.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.5

Joseph Sohm // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 11.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 4.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthInnovativeImages // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 14.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 6.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 8

You may also like: Libertarian, gerrymandering, and 50 other political terms you should know

InnovativeImages // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 14.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 6.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 8

You may also like: Libertarian, gerrymandering, and 50 other political terms you should know

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthReal Window Creative // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 15.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 9.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.25

Real Window Creative // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 15.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 9.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.25

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthGrindstone Media Group // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 17

- Gender identity policy tally: 6

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11

Grindstone Media Group // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 17

- Gender identity policy tally: 6

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthRob Pauley // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 17.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 9

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 8.75

Rob Pauley // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 17.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 9

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 8.75

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSuzanne Tucker // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 18

- Gender identity policy tally: 5.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 12.75

Suzanne Tucker // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 18

- Gender identity policy tally: 5.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 12.75

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 19

- Gender identity policy tally: 11.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.75

You may also like: Oldest cities in America

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 19

- Gender identity policy tally: 11.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.75

You may also like: Oldest cities in America

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 25.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 12.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 12.5

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 25.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 12.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 12.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 26

- Gender identity policy tally: 14.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11.5

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 26

- Gender identity policy tally: 14.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 27.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 14

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.5

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 27.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 14

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthTraveller70 // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 28

- Gender identity policy tally: 14.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.5

Traveller70 // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 28

- Gender identity policy tally: 14.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthFelix Lipov // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 29.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 16.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.25

You may also like: 25 terms you should know to understand the gun control debate

Felix Lipov // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 29.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 16.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.25

You may also like: 25 terms you should know to understand the gun control debate

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 31

- Gender identity policy tally: 16

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 31

- Gender identity policy tally: 16

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 32.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 16

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.5

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 32.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 16

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthBelikova Oksana // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 33.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 17.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.25

Belikova Oksana // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 33.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 17.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.25

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthRandy Runtsch // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 33.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 18.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15.25

Randy Runtsch // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 33.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 18.25

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15.25

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthMoab Republic // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 35

- Gender identity policy tally: 18

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

You may also like: Most and least popular senators in America

Moab Republic // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 35

- Gender identity policy tally: 18

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

You may also like: Most and least popular senators in America

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthOrhan Cam // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 36

- Gender identity policy tally: 19

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

Orhan Cam // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 36

- Gender identity policy tally: 19

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 36

- Gender identity policy tally: 18.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.5

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 36

- Gender identity policy tally: 18.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthJames Curzio // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 36.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 19.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

James Curzio // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 36.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 19.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthAlways Wanderlust / Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 36.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 20

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.75

Always Wanderlust / Shutterstock- Overall tally: 36.75

- Gender identity policy tally: 20

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.75

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 37

- Gender identity policy tally: 18.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.5

You may also like: Youngest and oldest presidents in U.S. history

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 37

- Gender identity policy tally: 18.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.5

You may also like: Youngest and oldest presidents in U.S. history

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 37

- Gender identity policy tally: 20

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 37

- Gender identity policy tally: 20

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 37.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 20

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.5

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 37.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 20

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthJacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 38

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.5

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 38

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 39

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.5

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 39

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.5

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.5

-

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthSundry Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 39.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.5

Sundry Photography // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 39.25

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.5

-

Here’s how much legislation in each state restricts or protects trans youthCreative Family // Shutterstock

- Overall tally: 39.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.75

You may also like: Most lopsided state legislatures in America

Creative Family // Shutterstock- Overall tally: 39.5

- Gender identity policy tally: 20.75

- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.75

You may also like: Most lopsided state legislatures in America

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesdariatorchukova // Shutterstock

On the surface, Americans and their legislators accept and understand LGBTQ+ individuals more now than even a decade ago. The Supreme Court's 2015 decision to legalize same-gender marriage remains one of the most tangible and significant wins for LGBTQ+ rights—yet many Americans continue to have complex (and sometimes contradictory) views on transgender issues, suggesting much of the growing acceptance of LGBTQ+ people has not extended to the trans community.

Trans, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people have long been marginalized in the U.S., both through legislation dating as far back as mid-19th century anti-cross-dressing laws and through cultural representation, such as the long-standing portrayal of trans characters as villains in film and television.

More recently, after several decades of increased visibility and some legislative wins for the LGBTQ+ community in the aftermath of Stonewall, a wave of conservative backlash targeting trans rights has fully materialized. Already as of March 2023, there are over 400 bills targeting transgender rights active across 46 state legislatures. Nineteen anti-trans laws have been passed since the beginning of the year, according to the Trans Legislation Tracker. Within the past several years, however, one group within the trans community has become the center of what many have dubbed the most recent moral panic: trans youth.

Legislation specifically targeting transgender youth began cropping up in state legislatures in 2020. By 2021, laws claiming to "protect children" from the "dangers" of gender-affirming medical care entered the cultural zeitgeist in earnest—claims that are flatly contradicted by leading scientists and medical organizations' findings that this type of care is not only safe but medically necessary. Some proposed legislation goes as far as naming parental support for a young person's gender-affirming care as child abuse and gives the state the right to take trans children away from their parents.

While anti-trans youth legislation outnumbers legislation to protect trans youth, several states have enacted or are considering laws intended to protect trans children. In August 2022, California passed a law providing refuge and gender-affirming care to families escaping anti-trans youth legislation. Colorado—formerly known as the "Hate State" for its history of passing anti-LGBTQ+ legislation throughout the 90s—made history when it passed legislation in January 2023 protecting gender-affirming medical care as an essential health benefit, becoming the first state to do so. In 2022, Hawaii passed legislation that requires health insurance companies to cover gender-affirming care deemed medically necessary.

Stacker took a look at state-by-state data from the Movement Advancement Project on sexual orientation and gender identity policies that affect transgender youth. All 50 states and Washington D.C. were then ranked by their total policy tallies—the number of laws and policies driving equality for LGBTQ+ people—with #51 being the most restrictive state and #1 being the most protective state for trans youth. Tallies are compared to totals from 2022 and ties are broken, when possible, by the tally for gender-inclusive laws and policies. Negative tallies mean more discrimination laws exist than protection laws.

The Movement Advancement Project's policy tally only accounts for passed legislation in each state. It does not take into account activism efforts, public sentiment, or whether these laws are implemented, all of which can potentially differ from the legislative actions of elected officials. Major categories of laws analyzed include "Relationship and Parental Recognition, Nondiscrimination, Religious Exemptions, LGBTQ Youth, Health Care, Criminal Justice, and Identity Documents." Both gender identity and sexual orientation policy tallies are included since many trans individuals are also impacted by sexual orientation legislation.

You may also like: Voter demographics of every state

dariatorchukova // Shutterstock

dariatorchukova // ShutterstockOn the surface, Americans and their legislators accept and understand LGBTQ+ individuals more now than even a decade ago. The Supreme Court's 2015 decision to legalize same-gender marriage remains one of the most tangible and significant wins for LGBTQ+ rights—yet many Americans continue to have complex (and sometimes contradictory) views on transgender issues, suggesting much of the growing acceptance of LGBTQ+ people has not extended to the trans community.

Trans, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people have long been marginalized in the U.S., both through legislation dating as far back as mid-19th century anti-cross-dressing laws and through cultural representation, such as the long-standing portrayal of trans characters as villains in film and television.

More recently, after several decades of increased visibility and some legislative wins for the LGBTQ+ community in the aftermath of Stonewall, a wave of conservative backlash targeting trans rights has fully materialized. Already as of March 2023, there are over 400 bills targeting transgender rights active across 46 state legislatures. Nineteen anti-trans laws have been passed since the beginning of the year, according to the Trans Legislation Tracker. Within the past several years, however, one group within the trans community has become the center of what many have dubbed the most recent moral panic: trans youth.

Legislation specifically targeting transgender youth began cropping up in state legislatures in 2020. By 2021, laws claiming to "protect children" from the "dangers" of gender-affirming medical care entered the cultural zeitgeist in earnest—claims that are flatly contradicted by leading scientists and medical organizations' findings that this type of care is not only safe but medically necessary. Some proposed legislation goes as far as naming parental support for a young person's gender-affirming care as child abuse and gives the state the right to take trans children away from their parents.

While anti-trans youth legislation outnumbers legislation to protect trans youth, several states have enacted or are considering laws intended to protect trans children. In August 2022, California passed a law providing refuge and gender-affirming care to families escaping anti-trans youth legislation. Colorado—formerly known as the "Hate State" for its history of passing anti-LGBTQ+ legislation throughout the 90s—made history when it passed legislation in January 2023 protecting gender-affirming medical care as an essential health benefit, becoming the first state to do so. In 2022, Hawaii passed legislation that requires health insurance companies to cover gender-affirming care deemed medically necessary.

Stacker took a look at state-by-state data from the Movement Advancement Project on sexual orientation and gender identity policies that affect transgender youth. All 50 states and Washington D.C. were then ranked by their total policy tallies—the number of laws and policies driving equality for LGBTQ+ people—with #51 being the most restrictive state and #1 being the most protective state for trans youth. Tallies are compared to totals from 2022 and ties are broken, when possible, by the tally for gender-inclusive laws and policies. Negative tallies mean more discrimination laws exist than protection laws.

The Movement Advancement Project's policy tally only accounts for passed legislation in each state. It does not take into account activism efforts, public sentiment, or whether these laws are implemented, all of which can potentially differ from the legislative actions of elected officials. Major categories of laws analyzed include "Relationship and Parental Recognition, Nondiscrimination, Religious Exemptions, LGBTQ Youth, Health Care, Criminal Justice, and Identity Documents." Both gender identity and sexual orientation policy tallies are included since many trans individuals are also impacted by sexual orientation legislation.

You may also like: Voter demographics of every state

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesMihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -10.50 (4.5 point decrease from 2022)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -8.75 (3 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -1.75 (1.5 point decrease)

Mihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -10.50 (4.5 point decrease from 2022)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -8.75 (3 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -1.75 (1.5 point decrease)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesKristi Blokhin // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -9.50 (5.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -7.50 (4 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -2.00 (1.5 point decrease)

Kristi Blokhin // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -9.50 (5.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -7.50 (4 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -2.00 (1.5 point decrease)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesJoseph Sohm // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -5.50 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -5.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.50 (no change)

Joseph Sohm // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -5.50 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -5.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.50 (no change)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesW. Scott McGill // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -5.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.50 (no change)

W. Scott McGill // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -5.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: -0.50 (no change)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesJoseph Sohm // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -4.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -6.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.00 (no change)

You may also like: The history of voting in the United States

Joseph Sohm // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -4.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -6.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.00 (no change)

You may also like: The history of voting in the United States

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -4.00 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 0.00 (0.5 point increase)

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -4.00 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.00 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 0.00 (0.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -3.50 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.50 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 1.00 (no change)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -3.50 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.50 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 1.00 (no change)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesJon Bilous // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -2.50 (2 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.50 (3 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.00 (1 point increase)

Jon Bilous // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: -2.50 (2 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -4.50 (3 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.00 (1 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesCrackerClips Stock Media // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 0.00 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -2.75 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.75 (no change)

CrackerClips Stock Media // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 0.00 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -2.75 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.75 (no change)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesf11photo // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 0.50 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -1.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.00 (0.5 point decrease)

You may also like: Experts rank the best US presidents of all time

f11photo // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 0.50 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -1.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 2.00 (0.5 point decrease)

You may also like: Experts rank the best US presidents of all time

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 1.75 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -2.75 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.50 (1 point increase)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 1.75 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -2.75 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.50 (1 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesEQRoy // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 3.25 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -3.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.25 (0.5 point increase)

EQRoy // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 3.25 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -3.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.25 (0.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 3.25 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 0.25 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.00 (0.5 point increase)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 3.25 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 0.25 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.00 (0.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesvmfreire // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 3.25 (2.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 0.00 (2 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.25 (0.5 point decrease)

vmfreire // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 3.25 (2.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 0.00 (2 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 3.25 (0.5 point decrease)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesJacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 4.00 (no change)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -1.25 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25 (no change)

You may also like: How cellphone use while driving has changed in America in the last 20 years

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 4.00 (no change)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -1.25 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25 (no change)

You may also like: How cellphone use while driving has changed in America in the last 20 years

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesMihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 4.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -0.50 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.00 (0.5 point increase)

Mihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 4.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: -0.50 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.00 (0.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 5.25 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 1.00 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.25 (no change)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 5.25 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 1.00 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.25 (no change)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 6.00 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 0.25 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.75 (0.5 point increase)

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 6.00 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 0.25 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.75 (0.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 7.50 (3.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 2.00 (3.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.50 (no change)

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 7.50 (3.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 2.00 (3.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.50 (no change)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 7.75 (no change)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 3.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.25 (0.5 point decrease)

You may also like: After Elizabeth II: Who is in the royal line of succession?

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 7.75 (no change)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 3.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 4.25 (0.5 point decrease)

You may also like: After Elizabeth II: Who is in the royal line of succession?

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSusan M Hall // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 9.25 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 1.50 (1.5 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.75 (0.5 point increase)

Susan M Hall // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 9.25 (1 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 1.50 (1.5 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.75 (0.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesRob Pauley // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 10.25 (7.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.00 (4 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25 (3.5 point decrease)

Rob Pauley // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 10.25 (7.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.00 (4 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 5.25 (3.5 point decrease)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesMihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 10.75 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 4.25 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.50 (0.5 point increase)

Mihai_Andritoiu // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 10.75 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 4.25 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.50 (0.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesZack Frank // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 12.75 (7 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 6.00 (5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.75 (2 point increase)

Zack Frank // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 12.75 (7 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 6.00 (5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.75 (2 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesInnovativeImages // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 12.75 (1.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.25 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.50 (0.5 point decrease)

You may also like: 30 iconic posters from World War II

InnovativeImages // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 12.75 (1.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.25 (1 point decrease)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 7.50 (0.5 point decrease)

You may also like: 30 iconic posters from World War II

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesJoseph Sohm // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 14.75 (3 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.75 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 9.00 (1.5 point increase)

Joseph Sohm // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 14.75 (3 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.75 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 9.00 (1.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesReal Window Creative // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 16.50 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 9.75 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.75 (0.5 point increase)

Real Window Creative // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 16.50 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 9.75 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 6.75 (0.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesGrindstone Media Group // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 17.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 6.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11.00 (no change)

Grindstone Media Group // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 17.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 6.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11.00 (no change)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSuzanne Tucker // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 18.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.25 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.25 (0.5 point increase)

Suzanne Tucker // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 18.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 5.25 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.25 (0.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 21.50 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 12.75 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 8.75 (1 point increase)

You may also like: Baby names that are illegal around the world

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 21.50 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 12.75 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 8.75 (1 point increase)

You may also like: Baby names that are illegal around the world

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 25.50 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 14.50 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11.00 (0.5 point decrease)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 25.50 (0.5 point decrease)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 14.50 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 11.00 (0.5 point decrease)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesTraveller70 // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 28.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 15.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.50 (no change)

Traveller70 // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 28.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 15.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.50 (no change)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 29.00 (3.75 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 15.25 (2.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.75 (1.25 point increase)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 29.00 (3.75 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 15.25 (2.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.75 (1.25 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 29.50 (2 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 14.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15.00 (1.5 point increase)

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 29.50 (2 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 14.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15.00 (1.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesFelix Lipov // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 30.75 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.75 (0.5 point increase)

You may also like: How America has changed since the first Census in 1790

Felix Lipov // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 30.75 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 13.75 (0.5 point increase)

You may also like: How America has changed since the first Census in 1790

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 33.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.00 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.00 (0.5 point decrease)

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 33.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.00 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.00 (0.5 point decrease)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 33.50 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.00 (1 point increase)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 33.50 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 16.00 (1 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesRandy Runtsch // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 34.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 18.75 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15.25 (no change)

Randy Runtsch // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 34.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 18.75 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 15.25 (no change)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesBelikova Oksana // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 35.00 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.50 (0.25 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.50 (1.25 point increase)

Belikova Oksana // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 35.00 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 17.50 (0.25 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.50 (1.25 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesMoab Republic // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 35.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 18.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.00 (no change)

You may also like: States with the most liberals

Moab Republic // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 35.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 18.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.00 (no change)

You may also like: States with the most liberals

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesAlways Wanderlust / Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.25 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.00 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.25 (0.5 point increase)

Always Wanderlust / Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.25 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.00 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.25 (0.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesJames Curzio // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.50 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.50 (0.5 point increase)

James Curzio // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.50 (1 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.50 (0.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 19.50 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.00 (0.5 point increase)

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 19.50 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.00 (0.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesOrhan Cam // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 19.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.00 (1 point increase)

Orhan Cam // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 37.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 19.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.00 (1 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 38.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.00 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.00 (0.5 point increase)

You may also like: 100 actors who served in the military

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 38.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.00 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.00 (0.5 point increase)

You may also like: 100 actors who served in the military

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesNagel Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 38.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.00 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.50 (0.5 point increase)

Nagel Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 38.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.00 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 17.50 (0.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 39.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.50 (no change)

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 39.50 (0.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.00 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 18.50 (no change)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesWangkun Jia // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 39.50 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.50 (2 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 19.00 (0.5 point increase)

Wangkun Jia // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 39.50 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.50 (2 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 19.00 (0.5 point increase)

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesJacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 39.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.50 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 19.00 (1.5 point increase)

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 39.50 (1.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 20.50 (no change)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 19.00 (1.5 point increase)

-

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesCreative Family // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 41.50 (2 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.25 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 20.25 (1.5 point increase)

You may also like: Iconic presidential photos from the year you were born

Creative Family // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 41.50 (2 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.25 (0.5 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 20.25 (1.5 point increase)

You may also like: Iconic presidential photos from the year you were born

-

State lawmakers are pushing anti-trans legislation at record ratesSundry Photography // Shutterstock

- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 41.75 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.75 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 20.00 (1.5 point increase)

Sundry Photography // Shutterstock- Overall LGBTQ-related laws and policies tally: 41.75 (2.5 point increase)

--- Gender identity policy tally: 21.75 (1 point increase)

--- Sexual orientation policy tally: 20.00 (1.5 point increase)