BRUSSELS — In the weeks since Chinese leader Xi Jinping won a third five-year term as president, setting him on course to remain in power for life, leaders and diplomats from around the world have beaten a path to his door. None more so than those from Europe.

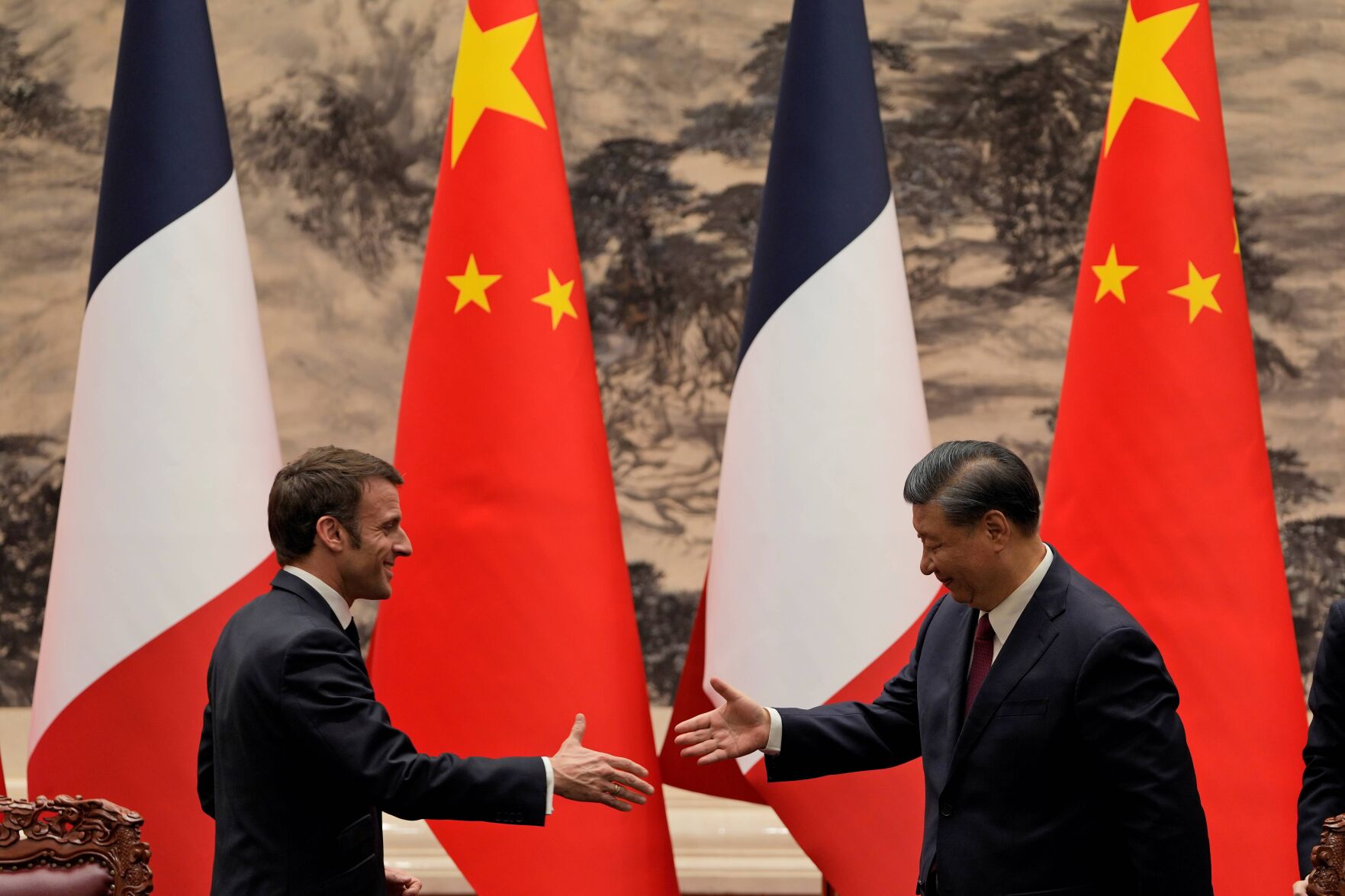

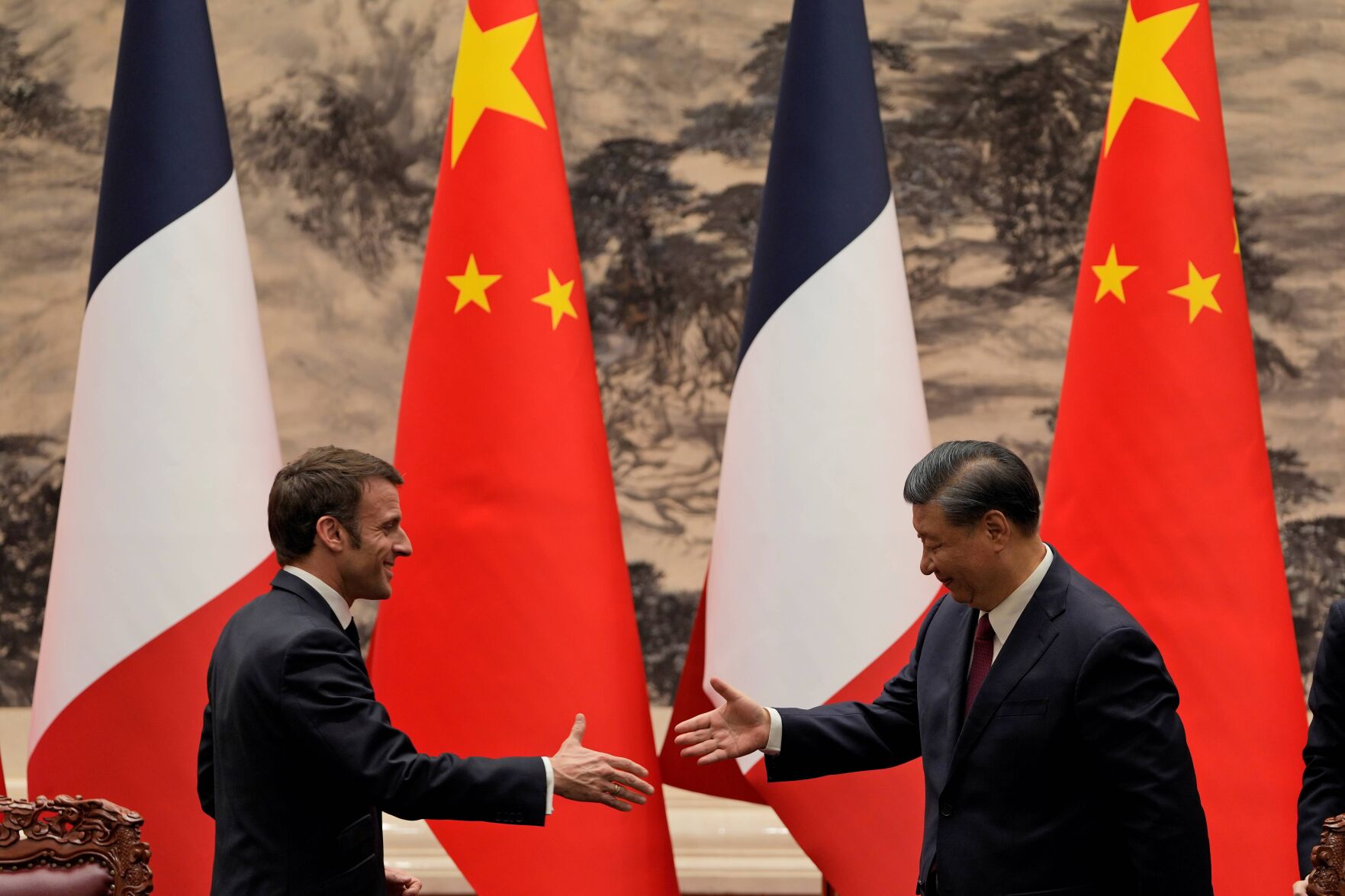

Ng Han Guan, Associated Press

French President Emmanuel Macron, left, shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping after meeting the press at the Great Hall of the People on April 6 in Beijing.

French President Emmanuel Macron made a high-profile state visit to Beijing earlier this month accompanied by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, just days after Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez.

German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock arrived in the northeast port city of Tianjin on April 13, following a visit by Chancellor Olaf Scholz in November.

For the 27-nation trading bloc, the reasons to head to China are clear.

As an ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Xi could play a pivotal role in helping to end the war in Ukraine. The conflict has dragged on for over a year, driven up energy prices and inflicted more damage on economies struggling to rebound from the coronavirus pandemic.

The Europeans want Xi’s help. They want him to talk to Ukraine’s president as well as Russia’s, but they don’t see him as the key mediator. China’s proposed peace plan for Ukraine is mostly a list of its previously known positions and is unacceptable, EU officials say.

The EU also fears that Xi might supply weapons to Russia. They’ve been particularly disturbed by Putin’s plans to deploy tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus. That announcement came just days after Xi and Putin met to cement their “no-limits friendship.”

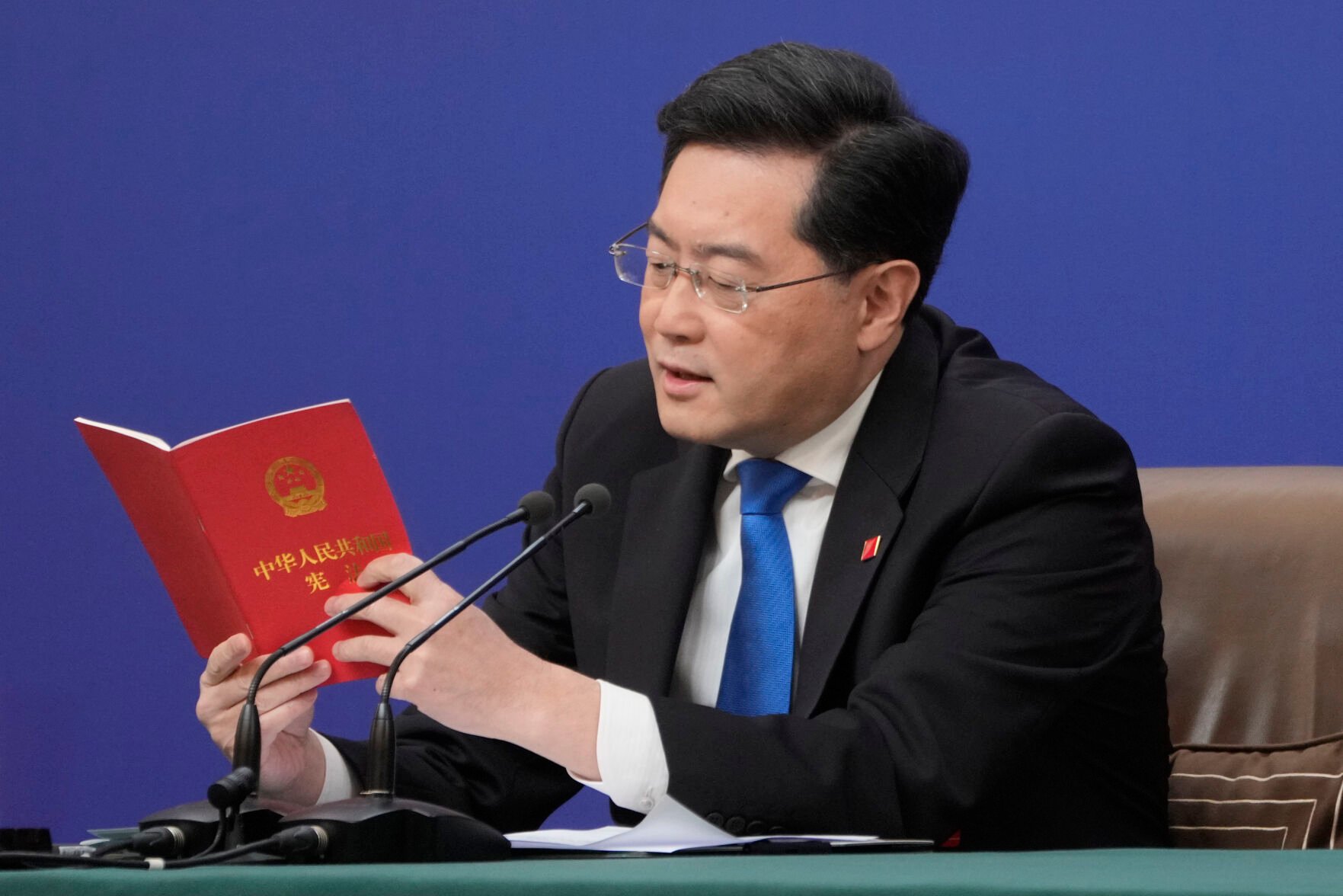

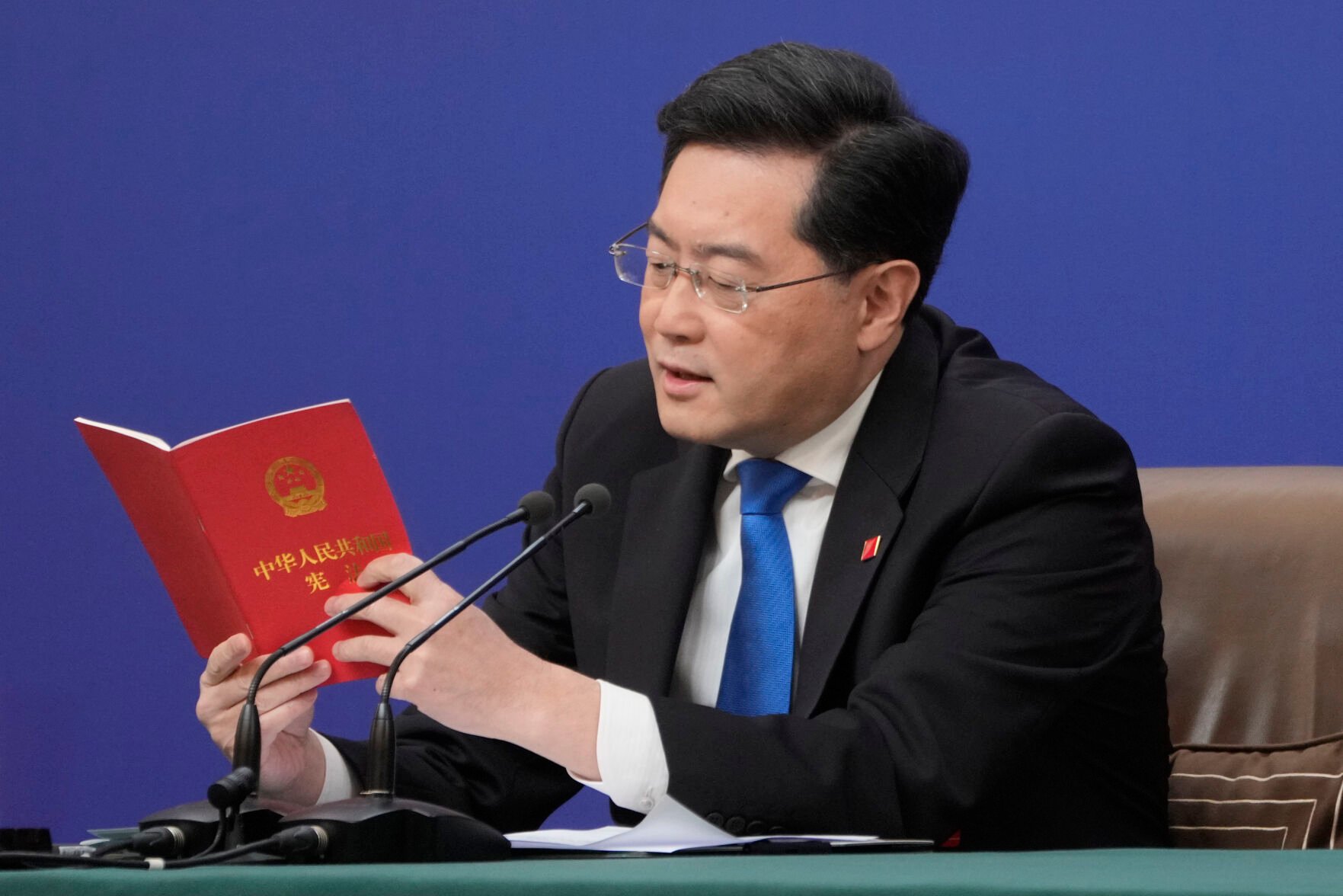

Mark Schiefelbein, Associated Press

Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang reads from the Chinese constitution when answering a question about Taiwan during a press conference held on the sidelines of the annual meeting of China's National People's Congress (NPC) on March 7 in Beijing.

Baerbock said the war is “top of my agenda.” Praising Beijing for easing tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran, she said that “its influence vis à vis Russia will have consequences for the whole of Europe and for our relationship with China.”

At the same time, the EU is deeply concerned about a military escalation in the Taiwan Strait. China launched war games just after Macron left. But unlike the U.S., with its military and strategic interest in Taiwan, the Europeans mostly see the island in economic and pro-democracy terms.

So the visits are meant to reassure Xi of respect for Beijing’s control over all of Chinese territory and to urge calm. They also highlight the challenge the U.S. faces as it tries to build a coalition of countries to ramp up pressure on Beijing over its expansionist policies.

“The key is that we have every interest, both in Europe and in China, to maintain the status quo,” a senior EU official said .

Beyond the geopolitics lies business. The EU and China did more than $2.5 billion worth of trade every day last year, and the Europeans don’t want to endanger that. However, the EU’s trade deficit has more than tripled over the past decade, and it wants to level the business playing field.

It’s also desperate to limit its imports of critical resources from China, like rare earth minerals or hi-tech components, after painfully weaning itself off its biggest, and most unreliable, gas supplier, Russia.

It’s a fine line to walk, and China is adept at divide-and-conquer politics.

Over the past two decades, the Chinese government has often used its economic heft to pry France, Germany and other allies away from the U.S. on issues ranging from military security and trade to human rights and Taiwan.

Beijing has called repeatedly for a “multi-polar world,” a reference to Chinese frustration with U.S. dominance of global affairs and the ruling Communist Party’s ambition to see the country become an international leader.

“There has been a serious deviation in U.S. understanding and positioning about China, treating China as the primary opponent and the biggest geopolitical challenge,” the Chinese foreign minister, Qin Gang, told reporters last month.

“China-Europe relations are not targeted, dependent, or subject to third parties,” he said.

Macron’s visit appeared to illustrate that Qin’s view isn’t just wishful thinking. As tensions rise between Beijing and Washington, the French leader said, it is important for Europe to retain its “strategic autonomy.”

“Being a friend doesn’t mean that you have to be a vassal,” Macron said, repeating a remark from his trip that alarmed some European partners. “Just because we’re allies, it doesn’t mean (that) we no longer have the right to think for ourselves.”

Such comments could strain ties with the U.S. and have also exposed divisions within the EU.

Without mentioning Macron, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki warned that some in Europe were too slow to heed the “wake-up call” on China.

“You could see this over the past couple of weeks as some European leaders went to Beijing,” Morawiecki said, adding: “I do not quite understand the idea of strategic autonomy, if it means de-facto shooting into our own knee.”

For its part, the White House has sought to downplay Macron’s talk of Europe as “an independent pole in a multi-polar world.”

It thinks European skepticism toward Beijing is growing. U.S. officials note a recent Dutch decision to restrict China’s access to advanced computer chip components or Scholz publicly prodding Xi not to deliver weapons to Russia.

Despite the differences of national emphasis, the EU’s strategy on China remains much as it was enshrined in 2019 — that the Asian giant is “a partner, a competitor and systemic rival.” The aim of the recent visits fit that mold: to secure Xi’s commitment to peace, keep trade flowing fairly and reduce Europe’s reliance on China for critical resources.

-

China says suspected spy balloon spotted over US is for research, accidently strayed

Xinhua

June 15, 1953: Born in Beijing, the son of Xi Zhongxun, a senior Communist Party official and former guerrilla commander in the civil war that brought the communists to power in 1949.

1969-75: At the age of 15, Xi is among many educated urban youths sent to live and work in poor rural villages during the Cultural Revolution, a period of social upheaval launched by then-leader Mao Zedong.

1975-79: Returns to Beijing to study chemical engineering at prestigious Tsinghua University.

1979-82: Joins military as aide in Central Military Commission and Defense Ministry.

Xinhua

June 15, 1953: Born in Beijing, the son of Xi Zhongxun, a senior Communist Party official and former guerrilla commander in the civil war that brought the communists to power in 1949.

1969-75: At the age of 15, Xi is among many educated urban youths sent to live and work in poor rural villages during the Cultural Revolution, a period of social upheaval launched by then-leader Mao Zedong.

1975-79: Returns to Beijing to study chemical engineering at prestigious Tsinghua University.

1979-82: Joins military as aide in Central Military Commission and Defense Ministry.

-

China says suspected spy balloon spotted over US is for research, accidently strayed

SUB

1982-85: Assigned as deputy and then leader of the Communist Party in Zhengding county, south of Beijing in Hebei province.

1985: Begins 17-year stint in coastal Fujian province, a manufacturing hub, as vice mayor of the city of Xiamen.

1987: Marries Peng Liyuan, a popular singer in the People’s Liberation Army’s song and dance troupe. They have one daughter. An earlier marriage for Xi fell apart after three years.

2000-2002: Governor of Fujian province.

2002: Transferred to neighboring Zhejiang province, where he is appointed party chief, a post that outranks governor in the Chinese system.

March 2007: Appointed party chief of Shanghai but stays only a few months.

October 2007: Joins national leadership as one of nine members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the top leadership of the Communist Party.

March 2008: Named vice president of China.

August 2011: Xi hosts then-Vice President Joe Biden on the latter's visit to China, nearly a decade before Biden becomes U.S. president.

SUB

1982-85: Assigned as deputy and then leader of the Communist Party in Zhengding county, south of Beijing in Hebei province.

1985: Begins 17-year stint in coastal Fujian province, a manufacturing hub, as vice mayor of the city of Xiamen.

1987: Marries Peng Liyuan, a popular singer in the People’s Liberation Army’s song and dance troupe. They have one daughter. An earlier marriage for Xi fell apart after three years.

2000-2002: Governor of Fujian province.

2002: Transferred to neighboring Zhejiang province, where he is appointed party chief, a post that outranks governor in the Chinese system.

March 2007: Appointed party chief of Shanghai but stays only a few months.

October 2007: Joins national leadership as one of nine members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the top leadership of the Communist Party.

March 2008: Named vice president of China.

August 2011: Xi hosts then-Vice President Joe Biden on the latter's visit to China, nearly a decade before Biden becomes U.S. president.

-

-

China says suspected spy balloon spotted over US is for research, accidently strayed

STR

November 2012: Replaces Chinese President Hu Jintao as general secretary of the Communist Party, the top party position.

March 2013: Starts first five-year term as president of China.

2013-2014: China begins reclaiming land in the South China Sea to build islands, some with runways and other infrastructure, pushing its territorial claims to disputed areas in the vital waterway.

2017: China launches a harsh crackdown on the Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim ethnic groups in the Xinjiang region after extremist attacks. Mass detentions and human rights abuses draw international condemnation and accusations of genocide.

October 2017: The party enshrines his ideology, known as “Xi Jinping Thought," in its constitution as he starts a second five-year term as leader. This symbolically elevates him to Mao's level as a leader whose ideology is identified by his name.

March 2018: China's legislature abolishes a two-term limit on the presidency, signaling Xi's desire to stay in power for more than 10 years.

July 2018: The United States, under President Donald Trump, imposes tariffs on Chinese imports, starting a trade war. China retaliates with tariffs on U.S. goods.

June-November 2019: Massive protests demanding greater democracy paralyze Hong Kong. Xi's government responds by imposing a national security law in mid-2020 that quashes dissent in the city.

January 2020: China locks down the city of Wuhan as a new virus sparks what will become the COVID-19 pandemic.

September 2020: Xi announces in a video speech to the U.N. General Assembly that China aims to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.

December 2020: Authorities announce an anti-monopoly investigation into e-commerce giant Alibaba, the start of a crackdown on China's high-flying tech companies.

August 2022: China launches missiles and deploys warships and fighter jets in major military exercises around Taiwan following the visit of a senior U.S. lawmaker, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, to the self-governing island that China claims as its territory.

October 2022: Xi starts a third five-year term as Communist Party leader, breaking with recent precedent that limited leaders to two terms.

STR

November 2012: Replaces Chinese President Hu Jintao as general secretary of the Communist Party, the top party position.

March 2013: Starts first five-year term as president of China.

2013-2014: China begins reclaiming land in the South China Sea to build islands, some with runways and other infrastructure, pushing its territorial claims to disputed areas in the vital waterway.

2017: China launches a harsh crackdown on the Uyghur and other predominantly Muslim ethnic groups in the Xinjiang region after extremist attacks. Mass detentions and human rights abuses draw international condemnation and accusations of genocide.

October 2017: The party enshrines his ideology, known as “Xi Jinping Thought," in its constitution as he starts a second five-year term as leader. This symbolically elevates him to Mao's level as a leader whose ideology is identified by his name.

March 2018: China's legislature abolishes a two-term limit on the presidency, signaling Xi's desire to stay in power for more than 10 years.

July 2018: The United States, under President Donald Trump, imposes tariffs on Chinese imports, starting a trade war. China retaliates with tariffs on U.S. goods.

June-November 2019: Massive protests demanding greater democracy paralyze Hong Kong. Xi's government responds by imposing a national security law in mid-2020 that quashes dissent in the city.

January 2020: China locks down the city of Wuhan as a new virus sparks what will become the COVID-19 pandemic.

September 2020: Xi announces in a video speech to the U.N. General Assembly that China aims to peak carbon dioxide emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.

December 2020: Authorities announce an anti-monopoly investigation into e-commerce giant Alibaba, the start of a crackdown on China's high-flying tech companies.

August 2022: China launches missiles and deploys warships and fighter jets in major military exercises around Taiwan following the visit of a senior U.S. lawmaker, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, to the self-governing island that China claims as its territory.

October 2022: Xi starts a third five-year term as Communist Party leader, breaking with recent precedent that limited leaders to two terms.