Scientists finish decoding entire human genome

Scientists say they have finally assembled the full genetic blueprint for human life, adding the missing pieces to a puzzle nearly completed two decades ago.

An international team described the first-ever sequencing of a complete human genome – the set of instructions to build and sustain a human being – in research published Thursday in the journal Science. The previous effort, celebrated across the world, was incomplete because DNA sequencing technologies of the day weren’t able to read certain parts of it. Even after updates, it was missing about 8% of the genome.

“Some of the genes that make us uniquely human were actually in this ‘dark matter of the genome’ and they were totally missed,” said Evan Eichler, a University of Washington researcher who participated in the current effort and the original Human Genome Project. “It took 20-plus years, but we finally got it done.”

Many — including Eichler’s own students — thought it had been finished already. “I was teaching them, and they said, ‘Wait a minute. Isn’t this like the sixth time you guys have declared victory? I said, ‘No, this time we really, really did it!”

HOGP

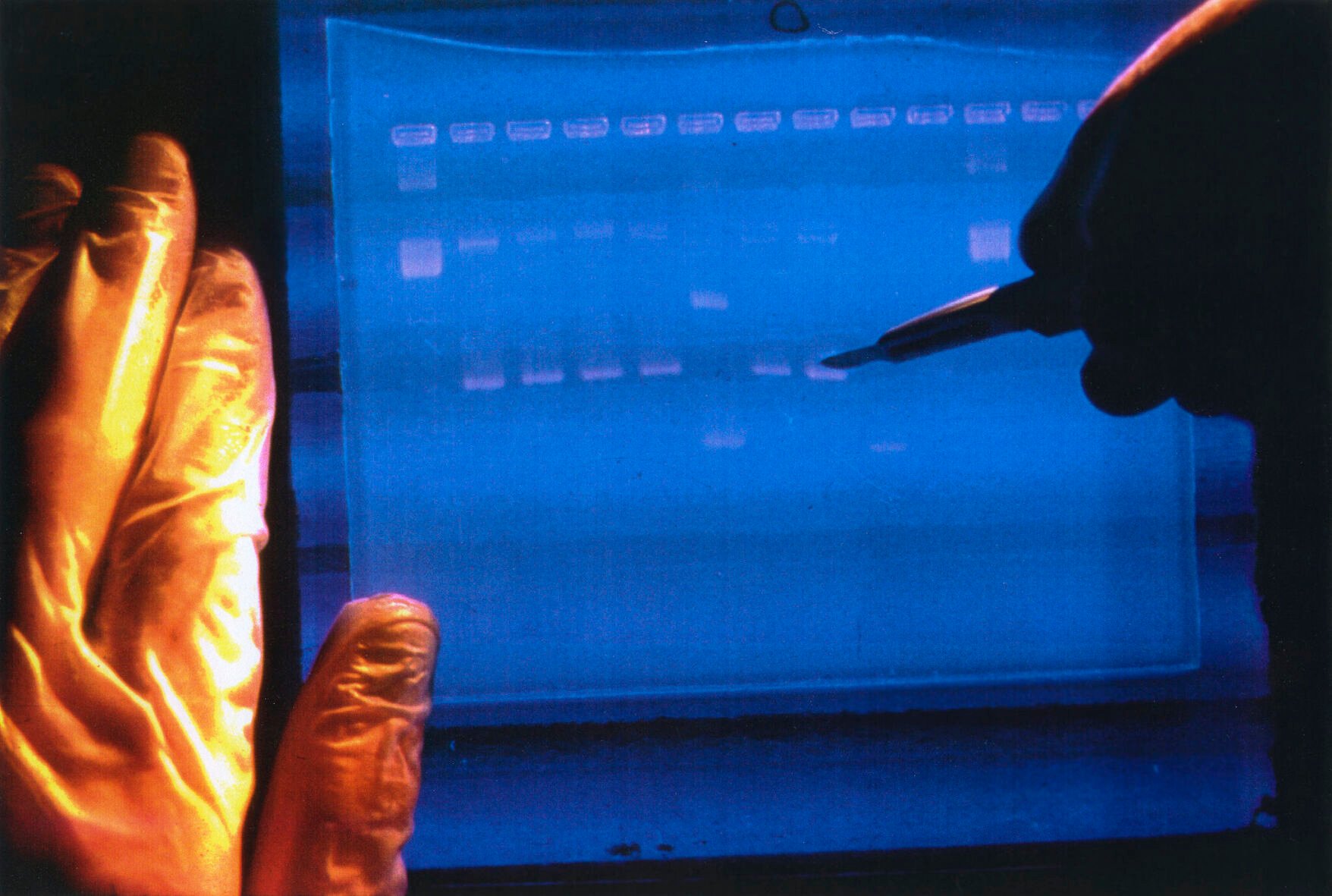

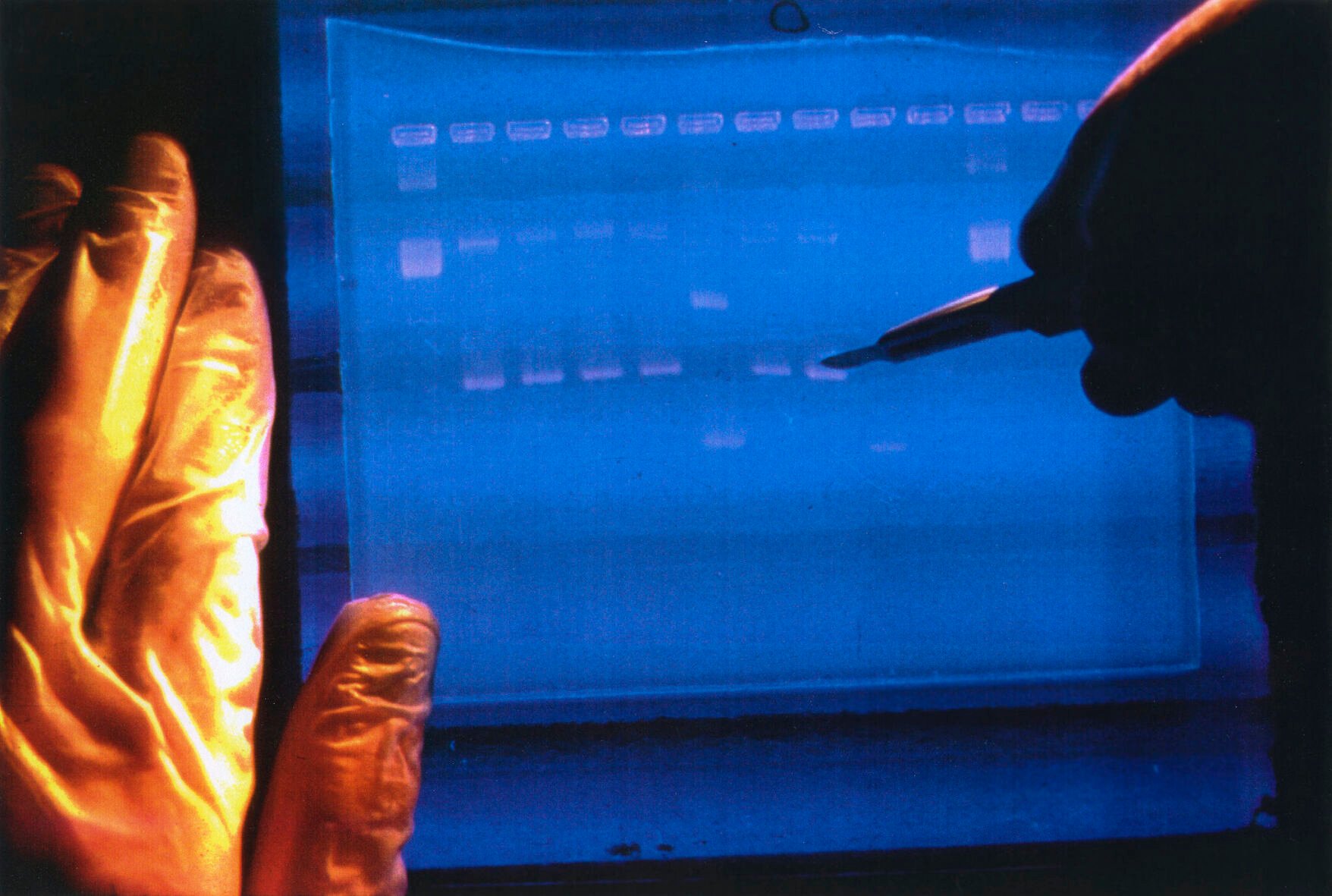

This undated image made available by the National Human Genome Research Institute shows the output from a DNA sequencer. In research published in the journal Science on Thursday, March 31, 2022, scientists announced they have finally assembled the full genetic blueprint for human life, adding the missing pieces to a puzzle nearly completed two decades ago. An international team described the sequencing of a complete human genome, the set of instructions to build a human being. (NHGRI via AP)

Scientists said this full picture of the genome will give humanity a greater understanding of our evolution and biology while also opening the door to medical discoveries in areas like aging, neurodegenerative conditions, cancer and heart disease.

“We’re just broadening our opportunities to understand human disease,” said Karen Miga, an author of one of the six studies published Thursday.

The research caps off decades of work. The first draft of the human genome was announced in a White House ceremony in 2000 by leaders of two competing entities: an international publicly funded project led by an agency of the U.S. National Institutes of Health and a private company, Maryland-based Celera Genomics.

The human genome is made up of about 3.1 billion DNA subunits, pairs of chemical bases known by the letters A, C, G and T. Genes are strings of these lettered pairs that contain instructions for making proteins, the building blocks of life. Humans have about 30,000 genes, organized in 23 groups called chromosomes that are found in the nucleus of every cell.

Before now, there were “large and persistent gaps that have been in our map, and these gaps fall in pretty important regions,” Miga said.

Evan Vucci

FILE - In this April 14, 2003 file photo, Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, announces the successful completion of the human genome project in Bethesda, Md. In research published in the journal Science on Thursday, March 31, 2022, scientists announced they have finally assembled the full genetic blueprint for human life, adding the missing pieces to a puzzle nearly completed two decades ago. An international team described the sequencing of a complete human genome, the set of instructions to build a human being. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File)

Miga, a genomics researcher at the University of California-Santa Cruz, worked with Adam Phillippy of the National Human Genome Research Institute to organize the team of scientists to start from scratch with a new genome with the aim of sequencing all of it, including previously missing pieces. The group, named after the sections at the very ends of chromosomes, called telomeres, is known as the Telomere-to-Telomere, or T2T, consortium.

Their work adds new genetic information to the human genome, corrects previous errors and reveals long stretches of DNA known to play important roles in both evolution and disease. A version of the research was published last year before being reviewed by scientific peers.

“This is a major improvement, I would say, of the Human Genome Project,” doubling its impact, said geneticist Ting Wang of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who was not involved in the research.

Eichler said some scientists used to think unknown areas contained “junk.” Not him. “Some of us always believed there was gold in those hills,” he said. Eichler is paid by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which also supports The Associated Press’s health and science department.

HOGP

In this undated image made available by the National Human Genome Research Institute, a researcher examines the output from a DNA sequencer. In research published in the journal Science on Thursday, March 31, 2022, scientists announced they have finally assembled the full genetic blueprint for human life, adding the missing pieces to a puzzle nearly completed two decades ago. An international team described the sequencing of a complete human genome, the set of instructions to build a human being. (NHGRI via AP)

Turns out that gold includes many important genes, he said, such as ones integral to making a person’s brain bigger than a chimp’s, with more neurons and connections.

To find such genes, scientists needed new ways to read life’s cryptic genetic language.

Reading genes requires cutting the strands of DNA into pieces hundreds to thousands of letters long. Sequencing machines read the letters in each piece and scientists try to put the pieces in the right order. That’s especially tough in areas where letters repeat.

Scientists said some areas were illegible before improvements in gene sequencing machines that now allow them to, for example, accurately read a million letters of DNA at a time. That allows scientists to see genes with repeated areas as longer strings instead of snippets that they had to later piece together.

Researchers also had to overcome another challenge: Most cells contain genomes from both mother and father, confusing attempts to assemble the pieces correctly. T2T researchers got around this by using a cell line from one “complete hydatidiform mole,” an abnormal fertilized egg containing no fetal tissue that has two copies of the father’s DNA and none of the mother’s.

The next step? Mapping more genomes, including ones that include collections of genes from both parents. This effort did not map one of the 23 chromosomes that is found in males, called the Y chromosome, because the mole contained only an X.

Wang said he’s working with the T2T group on the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium, which is trying to generate “reference,” or template, genomes for 350 people representing the breadth of human diversity.

“Now we’ve gotten one genome right and we have to do many, many more,” Eichler said. “This is the beginning of something really fantastic for the field of human genetics.”

__

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Pixabay

Prior to early 2020, the average person never uttered the word ‘coronavirus’ and had no reason to think they would soon be part of a global effort to practice social distancing. As the COVID-19 surged, these terms, and others, became commonplace in news reports and daily conversations.

Stacker consulted encyclopedias and public health websites to compile a list of 25 virology terms. These terms help build background knowledge on what viruses are, how contagious they are, how they work in living cells, how they spread, and how they affect humans. These definitions illustrate the difference between the common cold and the COVID-19 virus and why COVID-19 is so deadly. The terms also help show why self-isolation and quarantine—as well as social distancing—are critical, as these practices help “flatten the curve” and prevent an exponential rise in COVID-19 cases and deaths. This story will also highlight terms such as capsid, R0, and zoonosis that are increasingly used in news stories.

Keep reading for fast lessons in droplet spread, community transmission, quarantine, and many more COVID-19-related terms.

You may also like: Top 100 causes of death in America

Pixabay

Prior to early 2020, the average person never uttered the word ‘coronavirus’ and had no reason to think they would soon be part of a global effort to practice social distancing. As the COVID-19 surged, these terms, and others, became commonplace in news reports and daily conversations.

Stacker consulted encyclopedias and public health websites to compile a list of 25 virology terms. These terms help build background knowledge on what viruses are, how contagious they are, how they work in living cells, how they spread, and how they affect humans. These definitions illustrate the difference between the common cold and the COVID-19 virus and why COVID-19 is so deadly. The terms also help show why self-isolation and quarantine—as well as social distancing—are critical, as these practices help “flatten the curve” and prevent an exponential rise in COVID-19 cases and deaths. This story will also highlight terms such as capsid, R0, and zoonosis that are increasingly used in news stories.

Keep reading for fast lessons in droplet spread, community transmission, quarantine, and many more COVID-19-related terms.

You may also like: Top 100 causes of death in America

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Pixabay

A virus is a microscopic, infectious cellular invader. Viruses insert themselves into living cells where they replicate. They can infect most life forms: from bacteria to plants to animals. Every cellular organism studied so far has its own viruses. Millions of viruses are found across all ecosystems and life forms on Earth, with about 5,000 of these described by science.

Pixabay

A virus is a microscopic, infectious cellular invader. Viruses insert themselves into living cells where they replicate. They can infect most life forms: from bacteria to plants to animals. Every cellular organism studied so far has its own viruses. Millions of viruses are found across all ecosystems and life forms on Earth, with about 5,000 of these described by science.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

motorolka // Shutterstock

A bacteriophage—or phage for short—is a virus that specializes in infecting bacteria. Most viruses are bacteriophages. These particular types of viruses are made of proteins that infect the bacterial cell, then they enclose the DNA or RNA genome within the cell. Bacteriophages are the most common entities on Earth and are found everywhere bacteria exist, which is across all environments on Earth.

motorolka // Shutterstock

A bacteriophage—or phage for short—is a virus that specializes in infecting bacteria. Most viruses are bacteriophages. These particular types of viruses are made of proteins that infect the bacterial cell, then they enclose the DNA or RNA genome within the cell. Bacteriophages are the most common entities on Earth and are found everywhere bacteria exist, which is across all environments on Earth.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Michael Peseta // Shutterstock

Viruses specialize on all different forms of cellular life; each virus evolved to infect different forms. Animal viruses infect only animals, and two fields of study separate their study. For non-human animals, the field is known as “veterinary virology,” while “medical virology” is the study of viruses and human beings. Viruses that affect humans are the most studied with many areas of research.

Michael Peseta // Shutterstock

Viruses specialize on all different forms of cellular life; each virus evolved to infect different forms. Animal viruses infect only animals, and two fields of study separate their study. For non-human animals, the field is known as “veterinary virology,” while “medical virology” is the study of viruses and human beings. Viruses that affect humans are the most studied with many areas of research.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Yabusaka // Shutterstock

The protein shell of a virus that helps it enter its target cell is called a capsid. It protects the gene material of the virus. Structures of capsids vary widely and may consist of numerous proteins.

Yabusaka // Shutterstock

The protein shell of a virus that helps it enter its target cell is called a capsid. It protects the gene material of the virus. Structures of capsids vary widely and may consist of numerous proteins.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Sta T // Shutterstock

Some capsids build what are called “viral envelopes” from the cell itself. These are lipid membranes the virus builds around itself, with lipid material of the cell’s inner membrane. Viral envelopes are thought to help the virus infect the target cell. Lipids are the cell’s fatty acids and are not water soluble.

You may also like: States where obesity is increasing the most

Sta T // Shutterstock

Some capsids build what are called “viral envelopes” from the cell itself. These are lipid membranes the virus builds around itself, with lipid material of the cell’s inner membrane. Viral envelopes are thought to help the virus infect the target cell. Lipids are the cell’s fatty acids and are not water soluble.

You may also like: States where obesity is increasing the most

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Juan Gaertner // Shutterstock

Endocytosis is the term for when a virus enters its target cell. Viruses infect their cells in various ways. In some cases, the virus enters the cell but leaves the capsid behind, on the outside of the cell. In enveloped viruses, the viral envelope fuses directly with the cell membrane then it enters the cell. Inside the cell, the capsid degrades and the genetic material of the virus is released.

Juan Gaertner // Shutterstock

Endocytosis is the term for when a virus enters its target cell. Viruses infect their cells in various ways. In some cases, the virus enters the cell but leaves the capsid behind, on the outside of the cell. In enveloped viruses, the viral envelope fuses directly with the cell membrane then it enters the cell. Inside the cell, the capsid degrades and the genetic material of the virus is released.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Jarun Ontakrai // Shutterstock

Some viruses have a special trait that allows them to enter and infect a cell, then go dormant. The virus may replicate in the cell at first, then stop. Viral latency refers to the time that viral genetic material can remain in the cell before being reactivated. If reactivated, the virus can reinfect the host without the host being re-exposed. HIV is known to have viral latency.

Jarun Ontakrai // Shutterstock

Some viruses have a special trait that allows them to enter and infect a cell, then go dormant. The virus may replicate in the cell at first, then stop. Viral latency refers to the time that viral genetic material can remain in the cell before being reactivated. If reactivated, the virus can reinfect the host without the host being re-exposed. HIV is known to have viral latency.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

ARENA Creative // Shutterstock

Zoonosis is when an infectious disease is transmitted from other vertebrate animals to humans. These kinds of infections can occur in natural conditions because vertebrate animals are genetically similar to humans. Some examples include the black plague, transmitted by rats; rabies, transmitted by bats, raccoons, and dogs; and anthrax, transmitted by sheep. More recently emergent human diseases like HIV, Ebola, and SARS likely arose from zoonosis.

ARENA Creative // Shutterstock

Zoonosis is when an infectious disease is transmitted from other vertebrate animals to humans. These kinds of infections can occur in natural conditions because vertebrate animals are genetically similar to humans. Some examples include the black plague, transmitted by rats; rabies, transmitted by bats, raccoons, and dogs; and anthrax, transmitted by sheep. More recently emergent human diseases like HIV, Ebola, and SARS likely arose from zoonosis.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

SmartPhotoLab // Shutterstock

SmartPhotoLab // Shutterstock

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

James Gathany // Wikimedia Commons

James Gathany // Wikimedia Commons

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

aeorgondo2 // Shutterstock

Infectious particles like viruses can travel on dust or simply be suspended in the air. These particles can settle onto various surfaces, then can stir up and re-suspend in the air. If an uninfected person is exposed to these infectious particles, that person can become infected via airborne transmission. Some people have caught measles by entering a room where people with measles had recently been.

aeorgondo2 // Shutterstock

Infectious particles like viruses can travel on dust or simply be suspended in the air. These particles can settle onto various surfaces, then can stir up and re-suspend in the air. If an uninfected person is exposed to these infectious particles, that person can become infected via airborne transmission. Some people have caught measles by entering a room where people with measles had recently been.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

DimaBerlin // Shutterstock

Community transmission occurs when an infectious disease arises in a community in which there is no connection to a known case, and/or no known history of travel into or out of a region with the disease.

DimaBerlin // Shutterstock

Community transmission occurs when an infectious disease arises in a community in which there is no connection to a known case, and/or no known history of travel into or out of a region with the disease.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Maridav // Shutterstock

The “basic reproduction number” is also known as R0 (“R-nought”), a measure that describes how easily a virus spreads. Specifically, R0 is an estimate of how many other people get infected by one infected person. For example, seasonal flu has an R0 of about 1.3 while COVID-19 estimates suggest 1.5 or more people can be infected by each carrier, with some research indicating an R0 factor being as high as 6.68. Changes to R0 can happen with how often people see others, location, and strength of the efforts to lower spread.

Maridav // Shutterstock

The “basic reproduction number” is also known as R0 (“R-nought”), a measure that describes how easily a virus spreads. Specifically, R0 is an estimate of how many other people get infected by one infected person. For example, seasonal flu has an R0 of about 1.3 while COVID-19 estimates suggest 1.5 or more people can be infected by each carrier, with some research indicating an R0 factor being as high as 6.68. Changes to R0 can happen with how often people see others, location, and strength of the efforts to lower spread.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Chaikom // Shutterstock

An epidemic is defined by Merriam Webster’s dictionary as “an outbreak of disease that spreads quickly and affects many individuals at the same time.” An epidemic is a situation in which a disease is actively spreading.

Chaikom // Shutterstock

An epidemic is defined by Merriam Webster’s dictionary as “an outbreak of disease that spreads quickly and affects many individuals at the same time.” An epidemic is a situation in which a disease is actively spreading.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Prostock-studio // Shutterstock

A pandemic results from an epidemic that has grown past geographic boundaries. It is a type of epidemic. It occurs over a wide geographic area and impacts “an exceptionally high proportion of the population”—likely a whole country or the entire world. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization categorized the new coronavirus (COVID-19) as a pandemic.

You may also like: Best states for health care

Prostock-studio // Shutterstock

A pandemic results from an epidemic that has grown past geographic boundaries. It is a type of epidemic. It occurs over a wide geographic area and impacts “an exceptionally high proportion of the population”—likely a whole country or the entire world. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization categorized the new coronavirus (COVID-19) as a pandemic.

You may also like: Best states for health care

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Mircea Moira // Shutterstock

Antiviral drugs are medications that are used to inhibit viruses and their development. Antibiotics typically destroy the infectious agent, but since viruses are not exactly alive, antiviral drugs are designed to interfere in some way with the virus.

Mircea Moira // Shutterstock

Antiviral drugs are medications that are used to inhibit viruses and their development. Antibiotics typically destroy the infectious agent, but since viruses are not exactly alive, antiviral drugs are designed to interfere in some way with the virus.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

CDC // Unsplash

Vaccines prevent disease. A vaccine contains the same germ that makes people sick, but it is rendered harmless: Either it’s killed or weakened to the point it does not cause illness. When the vaccine is injected into the body, the immune system responds by making antibodies, leading to the same immunity a person would have if they’d become sick and recovered. When enough people are immune, this protects whole populations because of the diminished chances of an outbreak.

CDC // Unsplash

Vaccines prevent disease. A vaccine contains the same germ that makes people sick, but it is rendered harmless: Either it’s killed or weakened to the point it does not cause illness. When the vaccine is injected into the body, the immune system responds by making antibodies, leading to the same immunity a person would have if they’d become sick and recovered. When enough people are immune, this protects whole populations because of the diminished chances of an outbreak.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Dragana Gordic // Shutterstock

The common cold is a viral infection of the nose and throat that causes various symptoms like sore throat, runny nose, headaches, cough, and low fever. Many viruses can lead to the common cold, and most healthy people recover from a cold in six to 10 days.

Dragana Gordic // Shutterstock

The common cold is a viral infection of the nose and throat that causes various symptoms like sore throat, runny nose, headaches, cough, and low fever. Many viruses can lead to the common cold, and most healthy people recover from a cold in six to 10 days.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Pixabay

The term coronavirus defines a “family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases, such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV). The novel coronavirus [most] recently discovered has been named SARS-CoV-2 and it causes COVID-19.” Coronaviruses are not the flu.

Pixabay

The term coronavirus defines a “family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases, such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV). The novel coronavirus [most] recently discovered has been named SARS-CoV-2 and it causes COVID-19.” Coronaviruses are not the flu.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Jarun Ontakrai // Shutterstock

The novel coronavirus that causes the disease COVID-19 is known as SARS-CoV-2. Although this new disease may have certain similar symptoms to seasonal flu, It is from a completely different family of virus, and its particular set of traits make it highly contagious and far deadlier. The Centers for Disease Control has an information sheet to help people decide if they might have the new coronavirus, and what to do if they are sick.

You may also like: States getting the least (and most) sleep

Jarun Ontakrai // Shutterstock

The novel coronavirus that causes the disease COVID-19 is known as SARS-CoV-2. Although this new disease may have certain similar symptoms to seasonal flu, It is from a completely different family of virus, and its particular set of traits make it highly contagious and far deadlier. The Centers for Disease Control has an information sheet to help people decide if they might have the new coronavirus, and what to do if they are sick.

You may also like: States getting the least (and most) sleep

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Gargonia // Shutterstock

Isolation separates those who have a disease from those who don’t, or who are not known to be sick. The public has been guided on isolating at home during the pandemic if they or their family members have symptoms. The CDC fact sheet also provides guidance on home isolation and what to do once you no longer have symptoms.

Gargonia // Shutterstock

Isolation separates those who have a disease from those who don’t, or who are not known to be sick. The public has been guided on isolating at home during the pandemic if they or their family members have symptoms. The CDC fact sheet also provides guidance on home isolation and what to do once you no longer have symptoms.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Jordan Hopkins // Unsplash

Social distancing is when people stay away from each other, avoid all crowds, and cancel large and small events and gatherings. Social distancing effectively keeps this virus from spreading between people, and thus saves lives—particularly in the current pandemic because of its extreme contagion and high fatality rate. Distancing has included closing schools, working remotely, staying at least 6 feet apart from other people, and connecting with loved ones using online platforms, phones, and social media.

Jordan Hopkins // Unsplash

Social distancing is when people stay away from each other, avoid all crowds, and cancel large and small events and gatherings. Social distancing effectively keeps this virus from spreading between people, and thus saves lives—particularly in the current pandemic because of its extreme contagion and high fatality rate. Distancing has included closing schools, working remotely, staying at least 6 feet apart from other people, and connecting with loved ones using online platforms, phones, and social media.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Mongkolchon Akesin // Shutterstock

If people have been exposed to someone with the contagious disease, quarantine separates and restricts their movement to see if they get sick. Quarantine helps ensure that if someone is already exposed, that they stay away from others. People can shed the infectious virus and infect others without knowing they’re contagious.

Mongkolchon Akesin // Shutterstock

If people have been exposed to someone with the contagious disease, quarantine separates and restricts their movement to see if they get sick. Quarantine helps ensure that if someone is already exposed, that they stay away from others. People can shed the infectious virus and infect others without knowing they’re contagious.

-

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

rawf8 // Shutterstock

“Flattening the curve” is a key way to save many, many lives by slowing the exponential spread of the disease. This allows time for health-care workers, hospitals, and related systems to help infected people, without becoming overwhelmed by exponentially rising numbers of seriously ill patients. It is very effective, may last from weeks to months, and could save tens of thousands of lives.

rawf8 // Shutterstock

“Flattening the curve” is a key way to save many, many lives by slowing the exponential spread of the disease. This allows time for health-care workers, hospitals, and related systems to help infected people, without becoming overwhelmed by exponentially rising numbers of seriously ill patients. It is very effective, may last from weeks to months, and could save tens of thousands of lives.

-

Coronavirus spreads in deer and other animals. Scientists worry about what that means for people

Yeexin Richelle // Shutterstock

Yeexin Richelle // Shutterstock