Among the more remarkable legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic is how quickly federal regulators, the health care industry and consumers moved to make at-home testing a reliable tool for managing a public health crisis.

But that fast-track focus is missing from another, less publicized epidemic: an explosion in sexually transmitted diseases that can cause chronic pain and infertility among infected adults and disable or kill infected newborns. The disparity has amplified calls from researchers, public health advocates and health care companies urging the federal government to greenlight at-home testing kits that could vastly multiply the number of Americans testing for STDs.

Online shoppers can already choose from more than a dozen self-testing kits, typically ranging in price from $69 to $500, depending on the brand and the variety of infections they can detect.

But, except for HIV tests, the Food and Drug Administration hasn’t approved STD test kits for use outside a medical setting. That leaves consumers unsure about their reliability even as at-home use grows dramatically.

The STD epidemic is “out of control,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security. “We know we are missing diagnoses. We know that contact tracing is happening late or not at all. If we’re really serious about tackling the STD crisis, we have to get more people diagnosed.”

Preliminary data for 2021 showed nearly 2.5 million reported cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis in the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported cases of syphilis and gonorrhea have been climbing for about a decade. In its most recent prevalence estimate, the agency said that on any given day, 1 in 5 Americans are infected with any of eight common STDs.

The push to make at-home testing for STDs as easy and commonplace as at-home COVID-19 and pregnancy testing is coming from several sectors. Public health officials say their overextended staffers can’t handle the staggering need for testing and surveillance. Diagnostic and pharmaceutical companies see a business opportunity in the unmet demand.

The medical science underpinning STD testing is not particularly new or mysterious. Depending on the test, it may involve collecting a urine sample, pricking a finger for blood, or swabbing the mouth, genitals, or anus for discharge or cell samples. Medical centers and community health clinics have performed such testing for decades.

The issue for regulators is whether sampling kits can be reliably adapted for in-home use. Unlike rapid antigen tests for COVID-19, which produce results in 15 to 20 minutes, the home STD kits on the market require patients to collect their own samples, and then package and mail them to a lab for analysis.

In the past three years, as the pandemic prompted clinics that provide low-cost care to drastically curtail in-person services, a number of public health departments — among them state agencies in Alabama, Alaska and Maryland — have started mailing free STD test kits to residents. Universities and nonprofits are also spearheading at-home testing efforts.

And dozens of commercial enterprises are jumping into or ramping up direct-to-consumer sales. Everly Health, a digital health company that sells a variety of lab tests online, reported sales for its suite of STD kits grew 120% in the first half of this year compared with the first half of 2021.

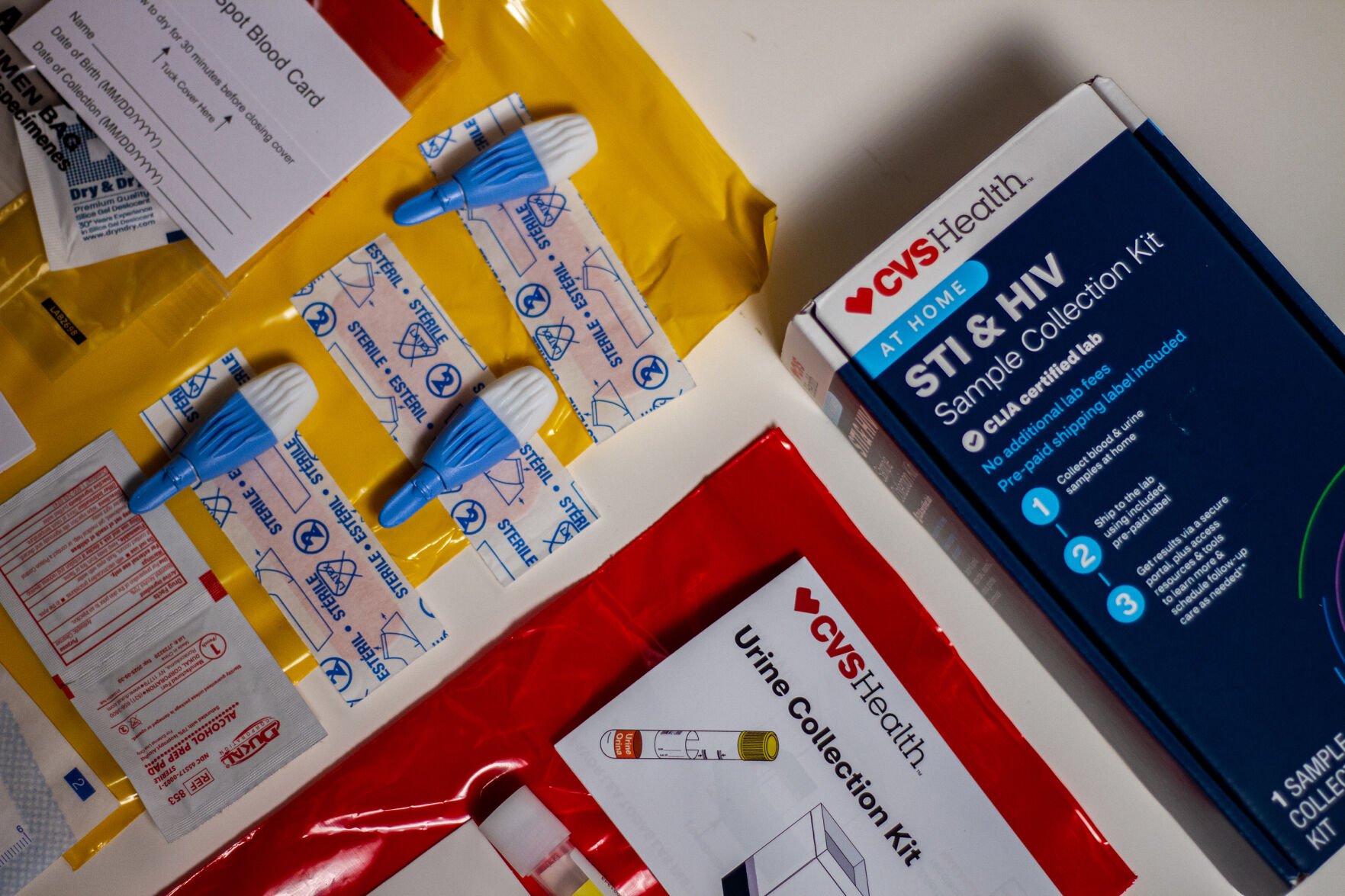

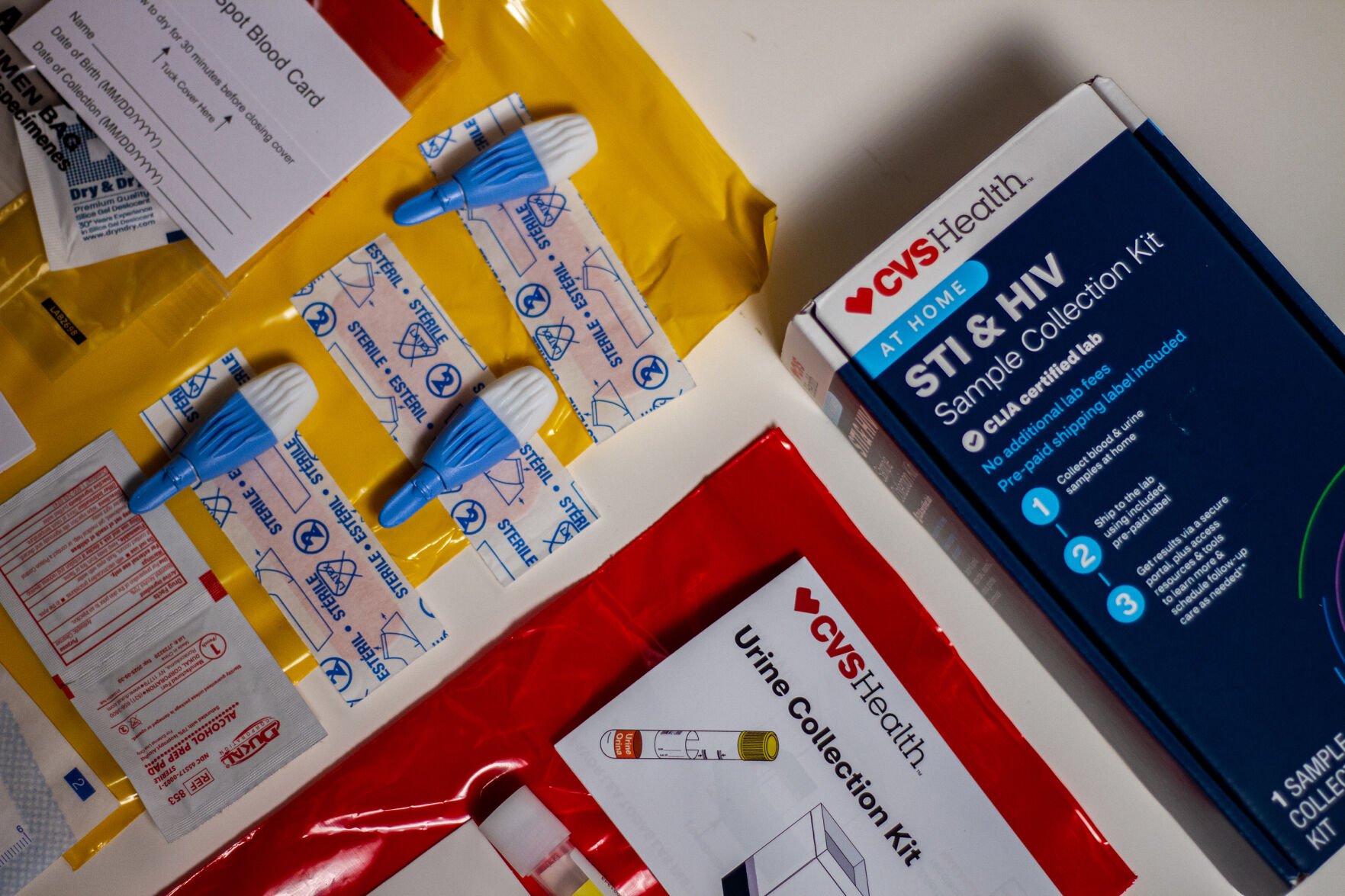

Eric Harkleroad/Kaiser Health News

CVS' at-home tests that screen for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections can be bought in stores and online. The kit is priced at $99.99.

CVS Health began selling its own bundled STD kit in October, priced at $99.99. Unlike most home kits, CVS’ version is available in stores.

Hologic, Abbott and Molecular Testing Labs are among the companies urgently developing tests. And Cue Health, which sells COVID-19 tests, is poised to launch a clinical trial for a rapid home test for chlamydia and gonorrhea that would set a new bar, providing results in about 20 minutes.

Alberto Gutierrez, who formerly led the FDA office that oversees diagnostic tests, said agency officials have been concerned about the reliability of home tests for years. The FDA wants companies to prove that home collection kits are as accurate as those used in clinics, and that samples don’t degrade during shipping.

“The agency doesn’t believe these tests are legally marketed at this point,” said Gutierrez, a partner at NDA Partners, a consulting firm that advises companies seeking to bring health care products to market.

“CVS should not be selling that test,” he added.

In response to KHN questions, the FDA said it considers home collection kits, which can include swabs, lancets, transport tubes and chemicals to stabilize the samples, to be devices that require agency review. The FDA “generally does not comment” on whether it plans to take action on any specific case, the statement said.

CVS spokesperson Mary Gattuso said the pharmacy chain is following the law. “We are committed to ensuring the products we offer are safe, work as intended, comply with regulations, and satisfy customers,” Gattuso said.

Everly Health and other companies described their kits as laboratory-developed tests, akin to the diagnostics some hospitals create for in-house use. And they contend their tests can be legally marketed because their labs have been certified by a different agency, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“The instruments and assays used by the laboratories we use are comparable to — and often the same as — those used by the labs a doctor’s office uses,” said Dr. Liz Kwo, chief medical officer at Everly Health. “Our at-home sample collection methods, like dried blood spots and saliva, have been widely used for decades.”

Home collection kits appeal to Uxmal Caldera, 27, of Miami Beach, Florida, who prefers to test in the privacy of his home. Caldera, who doesn’t have a car, said home testing saves him the time and expense of getting to a clinic.

Caldera has been testing himself for HIV and other STDs every three months for more than a year, part of routine monitoring for people taking PrEP, a regimen of daily pills to prevent HIV infection.

“Doing it by yourself is not hard at all,” said Caldera, who is uninsured but receives the tests free through a community foundation. “The instructions are really clear. I get the results in maybe four days. For sure, I would recommend it to other people.”

Dr. Leandro Mena, director of the CDC’s Division of STD Prevention, said he would like to see at-home STD testing become as routine as home pregnancy tests. An estimated 16 million to 20 million tests for gonorrhea and chlamydia are performed in the U.S. each year, Mena said. Widespread use of at-home STD testing, he said, could double or triple that number.

He noted that doctors have years of experience using home collection kits.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Point-of-Care Technologies Research for Sexually Transmitted Diseases has distributed roughly 23,000 at-home STD kits since 2004, said Charlotte Gaydos, a principal investigator with the center. The FDA generally allows such use if it’s part of research overseen by medical professionals. The center’s tests are now used by the Alaska health department, as well as Native American tribes in Arizona and Oklahoma.

Gaydos has published dozens of studies establishing that home collection kits for diseases such as chlamydia and gonorrhea are accurate and easy to use.

“There’s a huge amount of data showing that home testing works,” said Gaydos.

But Gaydos noted that her studies have been limited to small sample sizes. She said she doesn’t have the millions of dollars in funding it would take to run the sort of comprehensive trial the FDA typically requires for approval.

Jenny Mahn, director of clinical and sexual health at the National Coalition of STD Directors, said many public health labs are reluctant to handle home kits. “The public health labs won’t touch it without FDA’s blessing,” Mahn said.

“Home testing is the way of the future,” said Laura Lindberg, a professor of public health at Rutgers University. “The pandemic opened the door to testing and treatment at home without traveling to a health care provider, and we aren’t going to be able to put the genie back in the bottle.”

(KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.)

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

Naming diseases is a complicated business. To be useful, a name needs to be unique, descriptive, and memorable so it can be referenced easily, especially when medical situations become urgent. Though the easiest way to name illnesses may be just to give them identification numbers, that system becomes extraordinarily difficult to reference efficiently when time is of the essence.

It may seem intuitive to name diseases based on their origins or discovery locations; however, this approach also presents issues. As our world increasingly boasts a global citizenry, illnesses—and their names—can be spread across various cultures, making it essential to be sensitive to and inclusive of all who may encounter them.

In light of recent conversations about disease nomenclature, Stacker investigated how "monkeypox" and other disease names have caused controversy, using a collection of news, scientific, and government sources. While this is not an all-inclusive list of the issues surrounding the naming of diseases, it explores several fraught means by which illnesses are given nomenclature that becomes shorthand for public discussion.

You may also like: Fastest-warming states since 1970

Canva

Naming diseases is a complicated business. To be useful, a name needs to be unique, descriptive, and memorable so it can be referenced easily, especially when medical situations become urgent. Though the easiest way to name illnesses may be just to give them identification numbers, that system becomes extraordinarily difficult to reference efficiently when time is of the essence.

It may seem intuitive to name diseases based on their origins or discovery locations; however, this approach also presents issues. As our world increasingly boasts a global citizenry, illnesses—and their names—can be spread across various cultures, making it essential to be sensitive to and inclusive of all who may encounter them.

In light of recent conversations about disease nomenclature, Stacker investigated how "monkeypox" and other disease names have caused controversy, using a collection of news, scientific, and government sources. While this is not an all-inclusive list of the issues surrounding the naming of diseases, it explores several fraught means by which illnesses are given nomenclature that becomes shorthand for public discussion.

You may also like: Fastest-warming states since 1970

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

Naming illnesses based on where they were presumed to have originated was a common practice for decades. The "Spanish flu" from the early 1900s is just one of many toponymous diseases that earned its name based on a physical place. However, in 2015, the World Health Organization released new guidelines that advised against this practice. When an illness becomes irrevocably tied to a place, people from that place often face discrimination or violence—even if the illness is later proven to have come from someplace different.

One recent example of a toponymous disease causing backlash occurred at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when some people, including then-President Donald Trump, referred to the novel coronavirus as the "Wuhan flu" or the "Chinese virus." Many experts and medical professionals spoke up, stating that the monikers were xenophobic and prompted anti-Asian hate.

Other diseases named after places include the Zika virus, named after the Zika Forest in Uganda; Marburg virus, named after Marburg, Germany, where more than 30 cases of the illness were recorded; and Middle East respiratory syndrome, named after being first found in Saudi Arabia.

Canva

Naming illnesses based on where they were presumed to have originated was a common practice for decades. The "Spanish flu" from the early 1900s is just one of many toponymous diseases that earned its name based on a physical place. However, in 2015, the World Health Organization released new guidelines that advised against this practice. When an illness becomes irrevocably tied to a place, people from that place often face discrimination or violence—even if the illness is later proven to have come from someplace different.

One recent example of a toponymous disease causing backlash occurred at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when some people, including then-President Donald Trump, referred to the novel coronavirus as the "Wuhan flu" or the "Chinese virus." Many experts and medical professionals spoke up, stating that the monikers were xenophobic and prompted anti-Asian hate.

Other diseases named after places include the Zika virus, named after the Zika Forest in Uganda; Marburg virus, named after Marburg, Germany, where more than 30 cases of the illness were recorded; and Middle East respiratory syndrome, named after being first found in Saudi Arabia.

-

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

The list of diseases named after animal species is long and includes monkeypox, swine flu, and mad cow disease, among others. Though it may seem harmless to name an illness using its presumed species of origin or a carrier species, WHO guidelines also warn against this practice. In the wake of swine flu (also known as H1N1) outbreaks in other countries in 2009, Egypt ordered the slaughter of all pig livestock in the country despite not having any cases, resulting in the killing of about 300,000 animals.

Most recently, the name "monkeypox" has incited people to attack primates in zoos and their natural habitats out of fear of contracting the virus. WHO officials have attempted to redirect disease prevention efforts to focus on human-to-human transmission, but the prevalence of the "monkeypox" name isn't helping the cause. In addition, 29 experts wrote an article in August 2022 calling for the term "monkeypox" to be changed due to its racist connotations against Black people and people of African descent.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

Canva

The list of diseases named after animal species is long and includes monkeypox, swine flu, and mad cow disease, among others. Though it may seem harmless to name an illness using its presumed species of origin or a carrier species, WHO guidelines also warn against this practice. In the wake of swine flu (also known as H1N1) outbreaks in other countries in 2009, Egypt ordered the slaughter of all pig livestock in the country despite not having any cases, resulting in the killing of about 300,000 animals.

Most recently, the name "monkeypox" has incited people to attack primates in zoos and their natural habitats out of fear of contracting the virus. WHO officials have attempted to redirect disease prevention efforts to focus on human-to-human transmission, but the prevalence of the "monkeypox" name isn't helping the cause. In addition, 29 experts wrote an article in August 2022 calling for the term "monkeypox" to be changed due to its racist connotations against Black people and people of African descent.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Votava/brandstaetter images via Getty Images

It's not unusual for scientists to name their discoveries after themselves: Halley's Comet, Verreaux's sifaka, and Avogadro's number are just a few examples. But when it comes to physical illnesses, the politics of having an individual's name in the disease name becomes tricky. One such disease the WHO specifically named in its updated naming guidance is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, first described by neurologists Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Maria Jakob but named by a third neurologist, Walther Spielmeyer.

Names in this category are discouraged because they are not descriptive; however, the situation can be further complicated when the condition is named after a controversial figure. This is the case for Asperger's syndrome, which is no longer an official diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association as of 2013. Hans Asperger was a Nazi scientist during the Second World War and was responsible for the deaths of dozens of children; however, his dark story was not revealed publicly for many years after the diagnosis became common. The physical and mental conditions initially associated with Asperger's syndrome are now classified under the diagnosis of autism. However, laypeople still use the name despite its removal from official medical practices.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

Votava/brandstaetter images via Getty Images

It's not unusual for scientists to name their discoveries after themselves: Halley's Comet, Verreaux's sifaka, and Avogadro's number are just a few examples. But when it comes to physical illnesses, the politics of having an individual's name in the disease name becomes tricky. One such disease the WHO specifically named in its updated naming guidance is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, first described by neurologists Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Maria Jakob but named by a third neurologist, Walther Spielmeyer.

Names in this category are discouraged because they are not descriptive; however, the situation can be further complicated when the condition is named after a controversial figure. This is the case for Asperger's syndrome, which is no longer an official diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association as of 2013. Hans Asperger was a Nazi scientist during the Second World War and was responsible for the deaths of dozens of children; however, his dark story was not revealed publicly for many years after the diagnosis became common. The physical and mental conditions initially associated with Asperger's syndrome are now classified under the diagnosis of autism. However, laypeople still use the name despite its removal from official medical practices.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

-

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

At the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and before the virus had been studied in-depth, it was called "gay-related immunodeficiency" because of its prevalence among homosexual men. At the time, it was assumed that sexual orientation had to be a causal agent of the disease. Though it is now known that HIV is not caused by sexual orientation but is transmitted by sexual contact or contact with infected blood, homophobia still lingers around the disease, serving as a warning for future disease names to mitigate discrimination caused by nomenclature.

Beyond HIV, controversy ensued during outbreaks of H1N1, or swine flu, in Israel. Because Israel has large Jewish and Muslim populations, many of its citizens took offense to the reference to pigs in the flu's name because pigs are neither kosher nor halal. As a result, Israel's deputy health minister announced that the illness would instead be called "Mexican flu," based on the finding that the first human H1N1 patient was Mexican. This caused the Mexican ambassador to Israel to launch an official complaint against the Israeli government, ultimately resulting in Israel's acceptance of the term "swine flu" after all.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

Canva

At the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and before the virus had been studied in-depth, it was called "gay-related immunodeficiency" because of its prevalence among homosexual men. At the time, it was assumed that sexual orientation had to be a causal agent of the disease. Though it is now known that HIV is not caused by sexual orientation but is transmitted by sexual contact or contact with infected blood, homophobia still lingers around the disease, serving as a warning for future disease names to mitigate discrimination caused by nomenclature.

Beyond HIV, controversy ensued during outbreaks of H1N1, or swine flu, in Israel. Because Israel has large Jewish and Muslim populations, many of its citizens took offense to the reference to pigs in the flu's name because pigs are neither kosher nor halal. As a result, Israel's deputy health minister announced that the illness would instead be called "Mexican flu," based on the finding that the first human H1N1 patient was Mexican. This caused the Mexican ambassador to Israel to launch an official complaint against the Israeli government, ultimately resulting in Israel's acceptance of the term "swine flu" after all.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime