The heat is on, as middle July is climatologically the hottest time of year. Nationally, the core of the heat will be in the Southwest into early next week, with temperatures consistently 5 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit higher their normally hot midsummer levels.

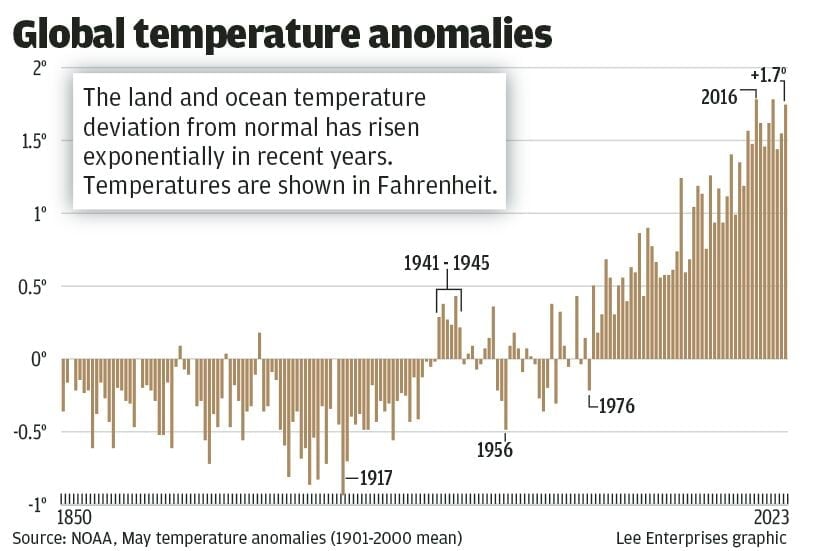

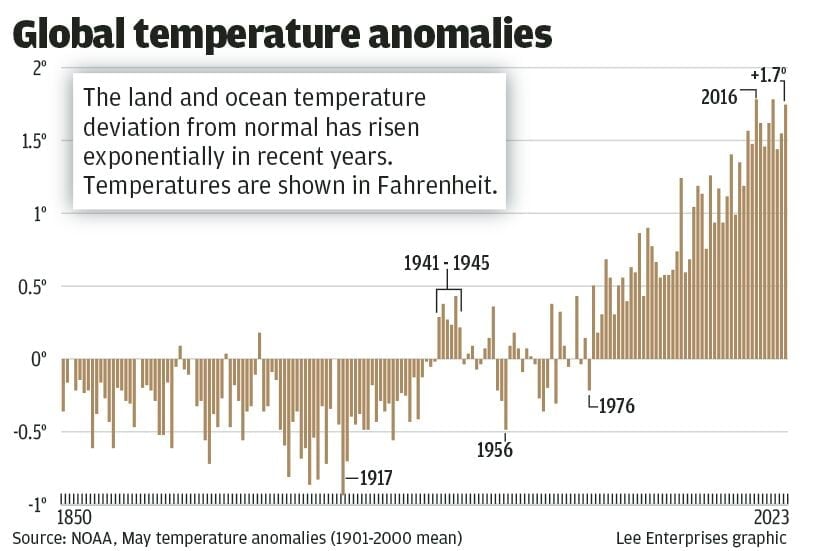

While much of the Middle Atlantic and the Southwest had a relatively cool interlude last month, it was the warmest June on record globally. A big reason was the exceedingly warm oceans, as they cover about 70 percent of the planet’s surface.

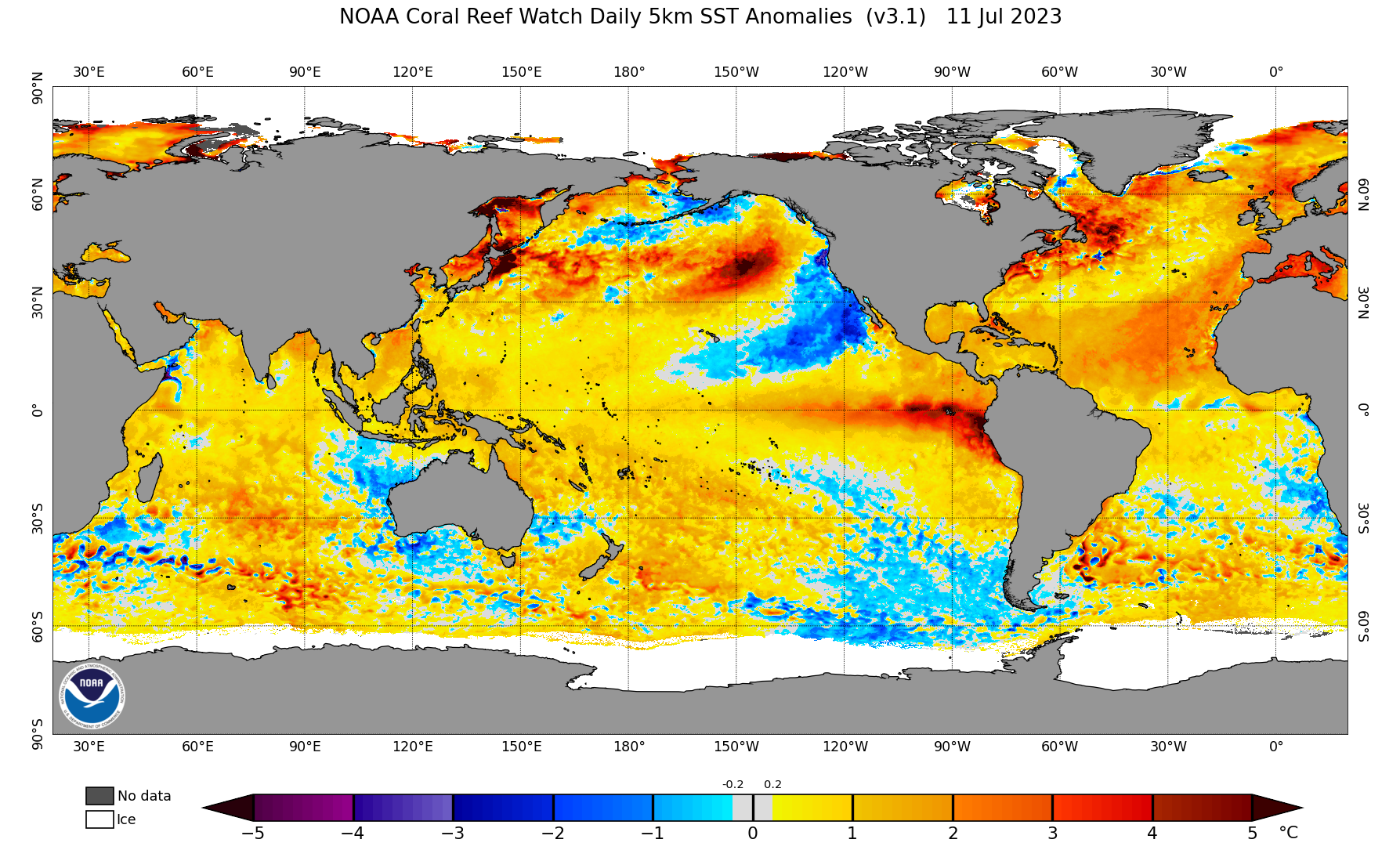

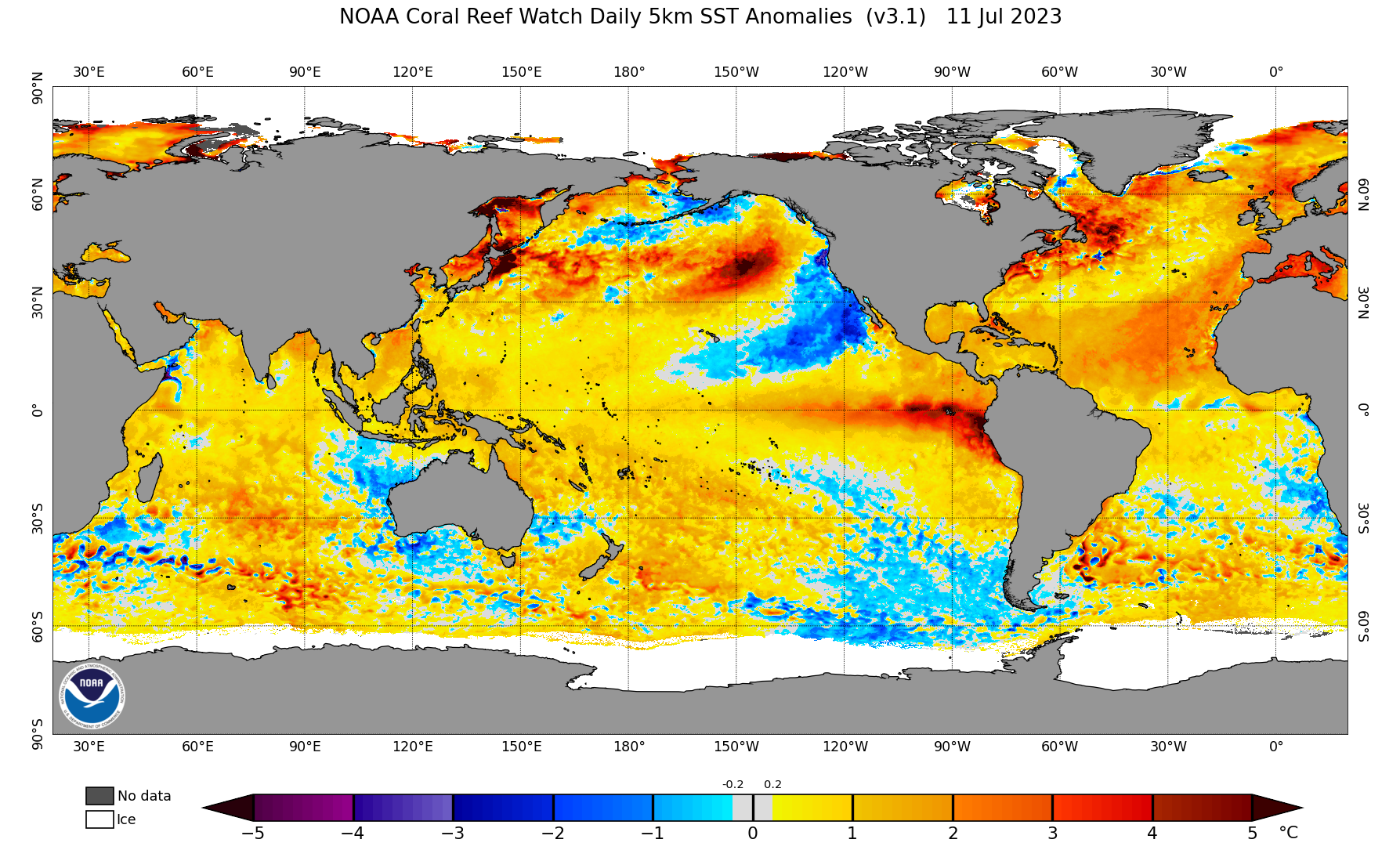

In the eastern Gulf of Mexico, which is already warm to begin with, water around the Florida Keys has been in the lower to middle 90s for much of the last week, about 5 to 6 degrees F higher than normal. Away from tropical waters, the differences are also striking, with about 2 million square miles of the North Atlantic Ocean at least 2 to 3 degrees F higher than normal.

Peter Pereira, Associated Press

Ja-Veah Cheney, 9, pours water over her head, taking shelter from the sweltering heat Wednesday at the splash pad station at Riverside Park in New Bedford, Mass.

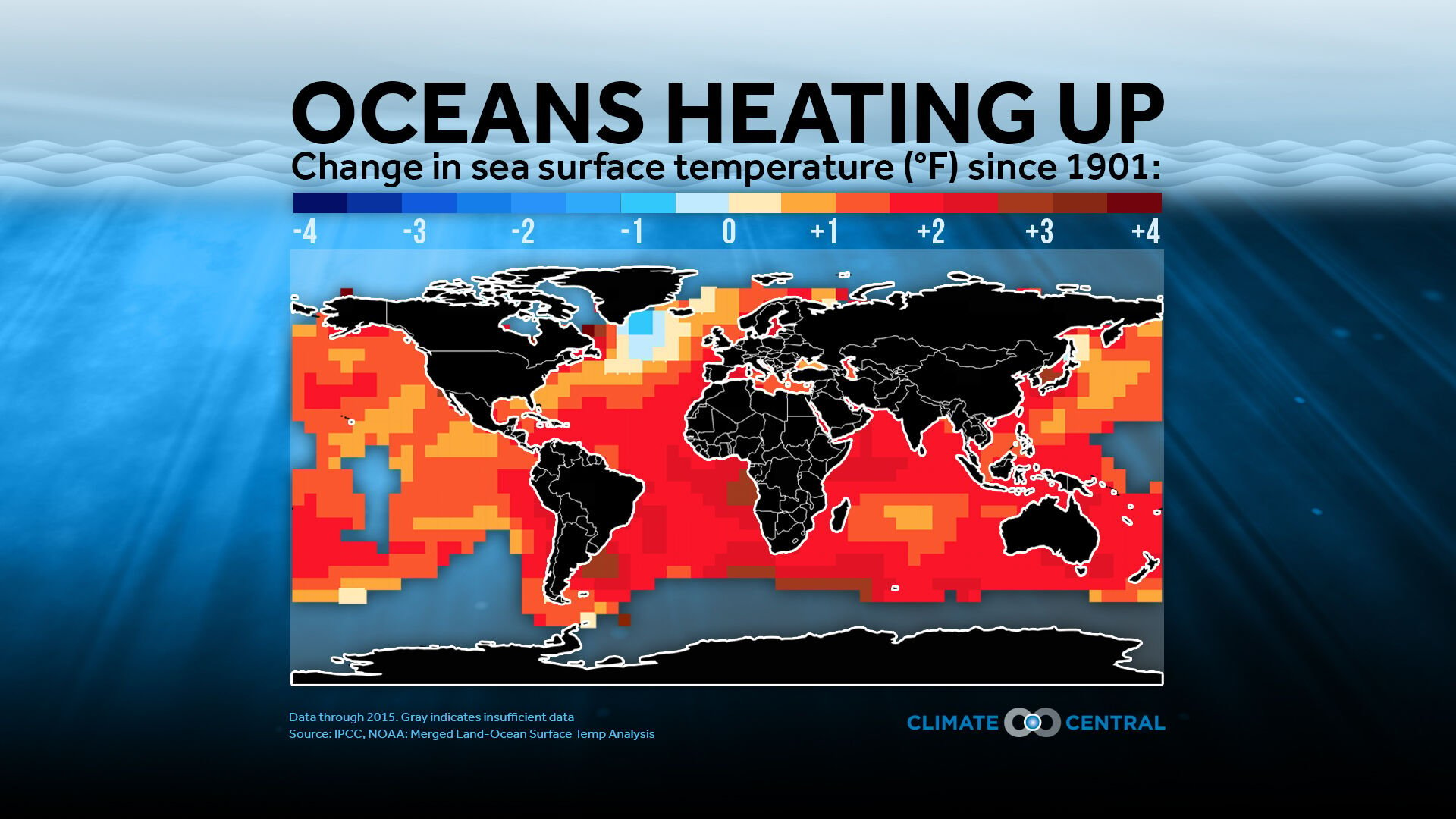

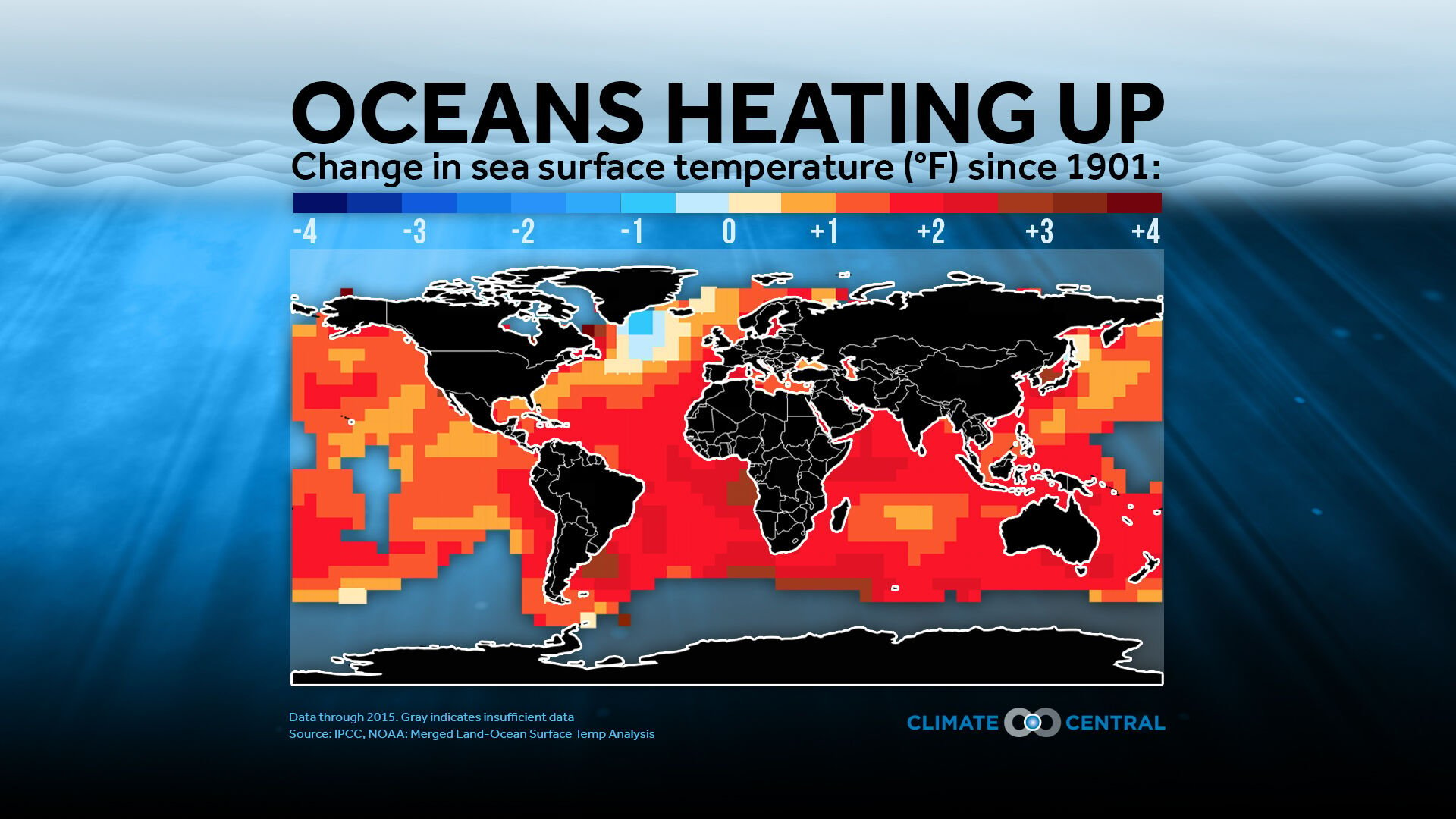

The warming climate is the main driver of long-term ocean temperature rise. Worldwide, they are about 1.5 degrees F higher than a century ago. But more recent influences are forcing the temperatures even higher this year.

The first is the current El Niño phenomenon. The central and eastern Pacific Ocean along the equator undergoes warming and cooling cycles every few years. These are related to how fast the east winds are moving in the tropics. El Niño is the warm phase; La Niña is the cool phase.

La Niña had been in place for the previous three years, but over the last few months, a rapid warming has developed. Ocean temperatures along the equator in the eastern Pacific Ocean are currently 6 degrees F higher than average. This very warm water is not limited to the top layer of the ocean; it extends about 100 yards deep.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Sea surface temperature difference from normal on July 11, 2023.

This back-and-forth is a regular recurring event in the Pacific, but recently, the warm episodes have been skewing even warmer than a few decades ago.

Away from the tropics, the recent warming of the North Atlantic has been the topic of much discussion in the scientific community. One possible reason for the warming relates to changes in the fuel used for cargo ships crisscrossing the ocean from North America to Europe.

To reduce pollution, a new agreement from the International Maritime Organization went into effect at the start of 2020, limiting the sulfur content in the fuel oil used by the ships.

When that fuel is burned, the ships emit sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, which reflects sunlight back into space. Unlike carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide lasts only a few weeks in the atmosphere. With the new fuel rules in place for a few years now, the amount of sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere has dropped dramatically over the heavily traveled shipping lanes of the North Atlantic.

All else being equal, this suggests more sunlight reaching the ocean, yielding a net warming. While there is probably some level of impact, its magnitude remains an open question and a topic for more research.

Another potential additive impact is the January 2022 eruption of an underwater volcano in the Tongan archipelago of the South Pacific. While eruptions usually cool the atmosphere temporarily, this volcano’s origins underwater may have had the opposite effect.

Two separate studies released earlier this year, one from the U.K., and one from NASA, suggest the volcano ejected millions of tons of water vapor into the stratosphere.

More than 15 miles high, the stratosphere is above where most regular weather processes would turn the water vapor into clouds and precipitation, so the water vapor gradually circulates around the earth. Because water vapor is a strong greenhouse gas, like carbon dioxide, that could be contributing to the warming.

CLIMATE CENTRAL

Change in global ocean temperature since 1901, showing data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Because it takes a lot of energy to change the temperature of water, it is not surprising that the extra warming signal is only being detected in the oceans now. The first half of 2023 has been the third warmest on record, and with the especially warm ocean right now, it is nearly certain this year will be one of the five warmest.

Regarding impacts, coral bleaching is one of the most visible connections to the warming oceans, but there are other consequences. Dependable fish populations will migrate and decline, stressing family fishing operations and impacting food security.

Michael Probst, Associated Press

People spend time in a public pool July 8 in Wehrheim near Frankfurt, Germany.

Back on land, even far away from the coast, these ocean-atmosphere connections lead to more serious humid heat waves, elevating heat stress and potential heat stroke to people who work outdoors or lack air conditioning.

The increased evaporation means more rain falls during the most intense storms, and the increasing rainfall rate heightens the flood risks along streams, creeks and rivers.

How much more warming and how much additional risk will largely depend on how quickly humanity reduces emissions of greenhouse gases in the coming decades — a direct consequence of the use of coal, oil and natural gas.

But for the rest of this year, expect the oceans to stay warm.

Sean Sublette is the chief meteorologist for the Richmond Times-Dispatch in Virginia.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Matt York, Associated Press

A jet takes flight from Sky Harbor International Airport as the sun sets Wednesday in Phoenix. Millions of people across the Southwest are living through a historic heat wave, with even the heat-experienced desert city of Phoenix being tested since temperatures have hit 110 degrees Fahrenheit for 13 consecutive days.

Matt York, Associated Press

A jet takes flight from Sky Harbor International Airport as the sun sets Wednesday in Phoenix. Millions of people across the Southwest are living through a historic heat wave, with even the heat-experienced desert city of Phoenix being tested since temperatures have hit 110 degrees Fahrenheit for 13 consecutive days.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Damian Dovarganes, Associated Press

Tourists protect a sleeping child from the sun Wednesday as they visit the Hollywood sign landmark in Los Angeles. Forecasters in Southern California say blistering conditions Thursday will build throughout the weekend in the central and southern parts of California, where many residents should prepare for the hottest weather of the year.

Damian Dovarganes, Associated Press

Tourists protect a sleeping child from the sun Wednesday as they visit the Hollywood sign landmark in Los Angeles. Forecasters in Southern California say blistering conditions Thursday will build throughout the weekend in the central and southern parts of California, where many residents should prepare for the hottest weather of the year.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Ohad Zwigenberg, Associated Press

Children cool off in a fountain Wednesday just outside of Jerusalem's Old City.

Ohad Zwigenberg, Associated Press

Children cool off in a fountain Wednesday just outside of Jerusalem's Old City.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Michael Probst, Associated Press

A man runs Thursday along a small road on the outskirts of Frankfurt, Germany, as the sun rises.

Michael Probst, Associated Press

A man runs Thursday along a small road on the outskirts of Frankfurt, Germany, as the sun rises.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Peter Pereira, The Standard-Times via Associated Press

Ja-Veah Cheney, 9, pours water over her head Wednesday as she takes shelter from the sweltering heat at the splash pad station at Riverside Park in New Bedford, Mass. Across the U.S., more than 111 million people are under extreme heat advisories, watches and warnings.

Peter Pereira, The Standard-Times via Associated Press

Ja-Veah Cheney, 9, pours water over her head Wednesday as she takes shelter from the sweltering heat at the splash pad station at Riverside Park in New Bedford, Mass. Across the U.S., more than 111 million people are under extreme heat advisories, watches and warnings.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Damian Dovarganes, Associated Press

A homeless man sleeps under the sun Wednesday in the Hollywood district of Los Angeles. After a historically wet winter and a cloudy spring, California's summer was in full swing Thursday as a heat wave that's been scorching much of the U.S. Southwest brings triple digit temperatures and an increased risk of wildfires. Blistering conditions will build Friday and throughout the weekend in the central and southern parts of California, where many residents should prepare for the hottest weather of the year, the National Weather Service warned.

Damian Dovarganes, Associated Press

A homeless man sleeps under the sun Wednesday in the Hollywood district of Los Angeles. After a historically wet winter and a cloudy spring, California's summer was in full swing Thursday as a heat wave that's been scorching much of the U.S. Southwest brings triple digit temperatures and an increased risk of wildfires. Blistering conditions will build Friday and throughout the weekend in the central and southern parts of California, where many residents should prepare for the hottest weather of the year, the National Weather Service warned.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Emilio Morenatti, Associated Press

A man jumps into the sea on a breakwater Wednesday in Barcelona, Spain.

Emilio Morenatti, Associated Press

A man jumps into the sea on a breakwater Wednesday in Barcelona, Spain.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Anis Belghoul, Associated Press

A woman carries her baby and a bottle of water on her head Saturday in Niger.

Anis Belghoul, Associated Press

A woman carries her baby and a bottle of water on her head Saturday in Niger.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Eric Gay, Associated Press

Migrants stop for a water break Tuesday as they walk in the Rio Grande behind concertina wire as they try to enter the U.S. from Mexico in Eagle Pass, Texas.

Eric Gay, Associated Press

Migrants stop for a water break Tuesday as they walk in the Rio Grande behind concertina wire as they try to enter the U.S. from Mexico in Eagle Pass, Texas.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Michael Probst, Associated Press

An Icelandic horse is sprayed with water at a stud farm in Wehrheim near Frankfurt, Germany, one of several nations gripped in potentially the hottest temperatures ever recorded in Europe.

Michael Probst, Associated Press

An Icelandic horse is sprayed with water at a stud farm in Wehrheim near Frankfurt, Germany, one of several nations gripped in potentially the hottest temperatures ever recorded in Europe.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Muhammad Sajjad, Associated Press

Youths jump into a commercial swimming pool to cool themselves off Thursday in Peshawar, Pakistan. Countries across the world are preparing emergency measures amid a heat wave projected to get much worse heading into the weekend.

Muhammad Sajjad, Associated Press

Youths jump into a commercial swimming pool to cool themselves off Thursday in Peshawar, Pakistan. Countries across the world are preparing emergency measures amid a heat wave projected to get much worse heading into the weekend.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Thomas Padilla, Associated Press

A woman enjoys the sun in the Tuileries gardens Monday in Paris, where temperatures are expected to keep rising.

Thomas Padilla, Associated Press

A woman enjoys the sun in the Tuileries gardens Monday in Paris, where temperatures are expected to keep rising.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Matt York, Associated Press

Salvation Army volunteer Francisca Corral, center, gives water to a man Tuesday at their Valley Heat Relief Station in Phoenix.

Matt York, Associated Press

Salvation Army volunteer Francisca Corral, center, gives water to a man Tuesday at their Valley Heat Relief Station in Phoenix.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Michael Probst, Associated Press

People spend time in a public pool Saturday in Wehrheim near Frankfurt, Germany.

Michael Probst, Associated Press

People spend time in a public pool Saturday in Wehrheim near Frankfurt, Germany.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Alessandra Tarantino, Associated Press

A woman uses an umbrella to take shelter from the sun Thursday as she walks in downtown Rome. Temperatures in parts of Mediterranean Europe were forecast to reach as high as 113 degrees starting Friday as a high-pressure system grips the region. Cerberus is named for the three-headed dog in ancient Greek mythology who guarded the gates to the underworld.

Alessandra Tarantino, Associated Press

A woman uses an umbrella to take shelter from the sun Thursday as she walks in downtown Rome. Temperatures in parts of Mediterranean Europe were forecast to reach as high as 113 degrees starting Friday as a high-pressure system grips the region. Cerberus is named for the three-headed dog in ancient Greek mythology who guarded the gates to the underworld.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Petros Giannakouris, Associated Press

A man holds an umbrella Thursday as he and other tourists enters the ancient Acropolis hill during a heat wave, in Athens, Greece. In Athens and other Greek cities, working hours were changed for the public sector and many businesses to avoid the midday heat, while air-conditioned areas were opened to the public. “It’s like being in Africa,” 24-year-old tourist Balint Jolan, from Hungary, said. “It’s not that much hotter than it is currently at home, but yes, it is difficult.”

Petros Giannakouris, Associated Press

A man holds an umbrella Thursday as he and other tourists enters the ancient Acropolis hill during a heat wave, in Athens, Greece. In Athens and other Greek cities, working hours were changed for the public sector and many businesses to avoid the midday heat, while air-conditioned areas were opened to the public. “It’s like being in Africa,” 24-year-old tourist Balint Jolan, from Hungary, said. “It’s not that much hotter than it is currently at home, but yes, it is difficult.”

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Andreea Alexandru, Associated Press

A boy shows off his swimming skills Wednesday while cooling off in the river Arges, outside Bucharest, Romania.

Andreea Alexandru, Associated Press

A boy shows off his swimming skills Wednesday while cooling off in the river Arges, outside Bucharest, Romania.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Manu Fernandez, Associated Press

A woman fans herself Monday in Madrid, Spain. “Italy, Spain, France, Germany and Poland are all facing a major heat wave, with temperatures expected to climb to 48 degrees Celsius on the islands of Sicily and Sardinia – potentially the hottest temperatures ever recorded in Europe” the European Space Agency said Thursday.

Manu Fernandez, Associated Press

A woman fans herself Monday in Madrid, Spain. “Italy, Spain, France, Germany and Poland are all facing a major heat wave, with temperatures expected to climb to 48 degrees Celsius on the islands of Sicily and Sardinia – potentially the hottest temperatures ever recorded in Europe” the European Space Agency said Thursday.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Darko Vojinovic

A man cools off at a fountain Thursday during a sunny day in Belgrade, Serbia.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Andy Wong, Associated Press

A woman wearing sun protection, headgear and sunglasses swims Monday as residents cool off on a sweltering day at an urban waterway in Beijing.

Andy Wong, Associated Press

A woman wearing sun protection, headgear and sunglasses swims Monday as residents cool off on a sweltering day at an urban waterway in Beijing.

-

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Vadim Ghirda, Associated Press

Youngsters cool off Wednesday in the river Arges, outside Bucharest, Romania.

Vadim Ghirda, Associated Press

Youngsters cool off Wednesday in the river Arges, outside Bucharest, Romania.

-

In unrelenting heat, millions plunge, drink and shelter to cool off

Petros Giannakouris, Associated Press

A newly married couple poses for photos Wednesday during sunset as a man takes a dip in the water in Lagonisi southeast of Athens.

Petros Giannakouris, Associated Press

A newly married couple poses for photos Wednesday during sunset as a man takes a dip in the water in Lagonisi southeast of Athens.