The cold formality of the letter is seared in Debra Long’s memory.

It began “Dear Claimant,” and said her 24-year-old son, Randy, who was fatally shot in April 2006, was not an “innocent” victim. Without further explanation, the New York state agency that assists violent-crime victims and their families refused to help pay for his funeral.

Seth Wenig, Associated Press

Debra Long walks near the tombstone of her son, Randy Long, on April 19 in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. An examination of data from 23 states shows that Black people are disproportionately denied aid from programs that reimburse victims of violent crime.

Randy was a father, engaged to be married and studying to become a juvenile probation officer when his life was cut short during a visit to Brooklyn with friends. His mother, angry and bewildered by the letter, wondered: What did authorities see — or fail to see — in Randy?

“It felt racial. It felt like they saw a young African American man who was shot and killed and assumed he must have been doing something wrong,” Long said. “But believe me when I say, not my son.”

Debra Long had bumped up against a well-intentioned corner of the criminal justice system that is often perceived as unfair.

Every state has a program to reimburse victims for lost wages, medical bills, funerals and other expenses, awarding hundreds of millions in aid each year. But an Associated Press examination found that Black victims and their families are disproportionately denied compensation in many states, often for subjective reasons that experts say are rooted in racial biases.

Seth Wenig, Associated Press

Debra Long reflects on her years-long effort to get reimbursed by the state for the funeral of her murdered son, Randy Long, at her home April 19 in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

The AP found disproportionately high denial rates in 19 out of 23 states willing to provide detailed racial data, the largest collection of such data to date. In some states, including Indiana, Georgia and South Dakota, Black applicants were nearly twice as likely as white applicants to be denied. From 2018 through 2021, the denials added up to thousands of Black families each year collectively missing out on millions of dollars in aid.

The reasons for the disparities are complex and eligibility rules vary somewhat by state, but experts — including leaders of some of the programs — point to a few common factors:

- State employees reviewing applications often base decisions on information from police reports and follow-up questionnaires that seek officers’ opinions of victims’ behavior — both of which may contain implicitly biased descriptions of events.

- Those same employees may be influenced by their own biases when reviewing events that led to victims’ injuries or deaths. Without realizing it, a review of the facts morphs into an assessment of victims’ perceived culpability.

- Many state guidelines were designed decades ago with biases that benefited victims who would make the best witnesses, disadvantaging those with criminal histories, unpaid fines or addictions, among others.

As the wider criminal justice system — from police departments to courts — reckons with institutional racism in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd, compensation programs are also beginning to scrutinize how their policies affect people of color.

“We have this long history in victims services in this country of fixating on whether people are bad or good,” said Elizabeth Ruebman, an expert with a national network of victims-compensation advocates and a former adviser to New Jersey’s attorney general on the state’s program.

As a result, Black and brown applicants tend to face more scrutiny because of implicit biases, Ruebman said.

Seth Wenig, Associated Press

Debra Long looks through documents about the murder of her son, Randy Long, and photographs from his life April 19 while at her home in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

In some states examined by AP, such as New York and Nebraska, the denial rates for Black and white applicants weren’t too far apart. But the data revealed apparent bias in other ways: While white families were more likely to be denied for administrative reasons, such as missing deadlines or seeking aid for crimes that aren’t covered, Black families were more likely to be denied for subjective reasons, such as whether they may have said or done something to provoke a violent crime.

In Delaware, where Black applicants accounted for less than half of the compensation requests between 2018 and 2021 but more than 63% of denials, officials acknowledged that even the best of intentions are no match for systemic bias.

“State compensation programs are downstream resources in a criminal justice system whose headwaters are inextricably commingled with the history of racial inequity in our country,” Mat Marshall, a spokesman for Delaware’s attorney general wrote in an email. “Even race-neutral policy at the programmatic level may not accomplish neutral outcomes under the shadows that race and criminal justice cast on one another.”

The financial impact of a crime-related injury or death can be significant. Out of pocket expenses for things like crime scene cleanup or medical care can add up to thousands of dollars, prompting people to take out loans, drain savings or rely on family members.

After Randy was killed, Debra Long paid for his funeral with money she had saved for a down payment on her first house. Seventeen years later, she still rents an apartment in Poughkeepsie, New York.

Thousands of people are denied compensation every year for reasons having nothing to do with the crime itself. They are denied because of victims’ behavior before or after a crime.

Applicants can be denied if police or other officials say they failed to cooperate with an investigation. That can inadvertently harm people who are wary of retribution for talking to police, or people who don’t have information. A Chicago woman who was shot in the back was denied for failing to cooperate even though she couldn’t identify the shooter because she never saw the person.

And compensation can be denied merely based on circumstantial evidence or suspicions, unlike the burden of proof that is necessary in criminal investigations.

Seth Wenig, Associated Press

Xia’la Long looks at the tombstone of her uncle, Randy Long, who was murdered in 2006 while posing for a photo April 19 at a cemetery in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

Many states deny compensation based on a vaguely defined category of behavior — often called “contributory misconduct” — that includes anything from using an insult during a fight to having drugs in your system. Other times people have been denied because police found drugs on the ground nearby.

In the data examined by AP, Black applicants were almost three times as likely as applicants of other races to be denied for behavior-based reasons, including contributory misconduct.

“A lot of times it’s perception,” said Chantay Love, the executive director of the Every Murder is Real Healing Center in Philadelphia.

Love rattles off recent examples: A man killed while trying to break up a fight was on parole and was denied compensation, the state reasoned, because he should have steered clear of the incident; another was stabbed to death, and the state said he contributed because he checked himself out of a mental-health treatment facility a few hours earlier against a doctor’s advice.

Long scoured the police account of her son’s shooting. She called detectives and pleaded to know if they had said anything to the Office of Victims Services that would have implicated her son in some kind of a crime. There was nothing in the report. And detectives said they hadn’t submitted any additional information.

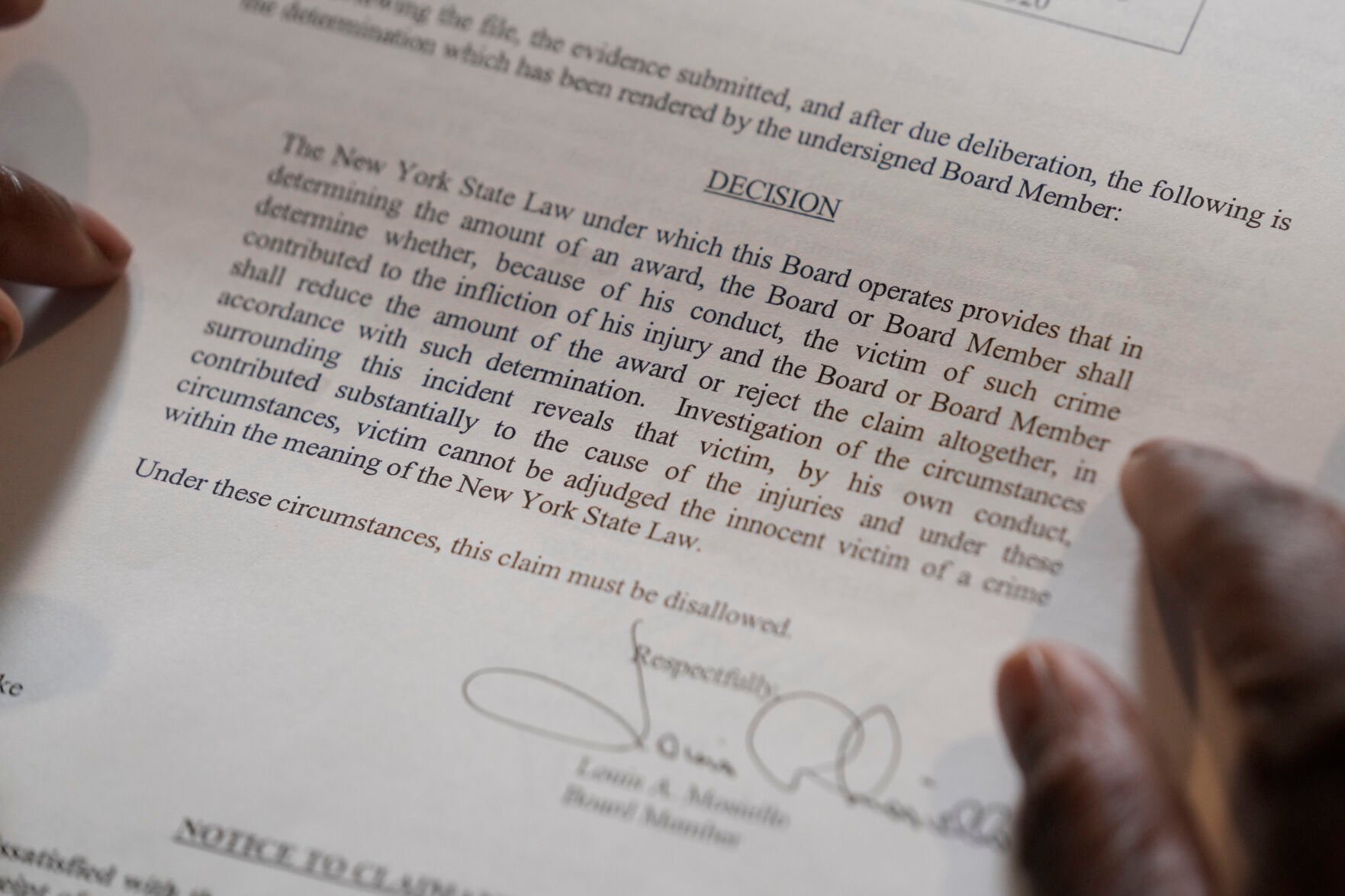

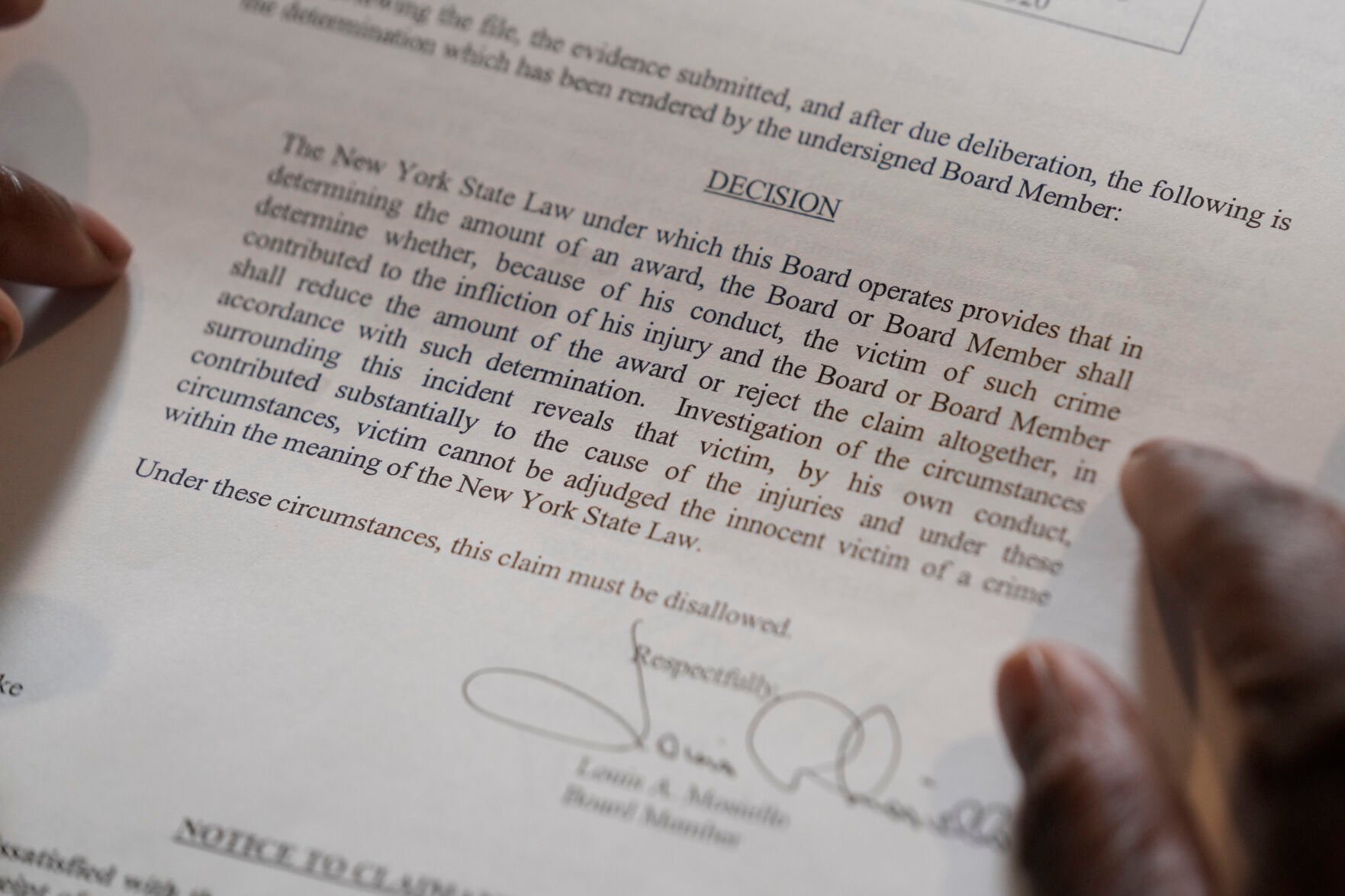

Seth Wenig, Associated Press

Debra Long holds the letter that explains why she was initially denied reimbursement for the funeral of her son, Randy Long, who was murdered in 2006.

Every chance Long got, she reminded detectives and the state officials reviewing her claim that Randy had never been in trouble with the police. She wanted them to understand the injustice was also being felt by Randy’s then-toddler son, who would only know his father through other people’s memories.

Long kept information about her son’s case in a box near her kitchen. As more than 20 notebooks full of conversations with detectives piled up, Long tucked the state’s rejection letter inside a folder so she wouldn’t lose it, but also so she didn’t have to see it every time she searched for something.

“What plays in their mind is that their loved one wasn’t important,” said Love of the Philadelphia-based advocacy group. “It takes the power away from it being a homicide, and it creates a portion of blame for the victim.”

In recent years, several states and cities have changed eligibility rules to focus less on victims’ behavior before or after crimes.

In Pennsylvania, a law went into effect in September that says applicants cannot be denied financial help with funerals or counseling services because of a homicide victim’s behavior. In Illinois, a new program director has retrained employees on ways unconscious bias can creep into their decisions. And in Newark, New Jersey, police have changed the language they use in reports to describe interactions with victims, leading to fewer denials for failure to cooperate.

Long, who now works as a victims advocate, was in a training in 2021 when a speaker began praising New York state’s compensation program. Long tried to stay quiet and get through the training, but couldn’t. She told the group about her experience and the weight of the letter.

Later, an Office of Victims Services employee approached Long and convinced her to reapply, saying the agency had been improved through training and other changes that would benefit her case. A few weeks later, and nearly 15 years after Randy was buried, Long’s application was approved and the state sent her a check for $6,000 — the amount she would have received back in 2006. She used part of that money to help Randy’s son, who is now in college, pay for summer classes.

“It’s not about the monetary amount,” Long said. “It was the way I felt I was treated.”

-

‘How do you protect a Black kid?’ Protesters demand justice in shooting of Kansas City teenager

Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Last September, Angel Pittman bought land in a small town 8 miles outside Salisbury, North Carolina, with plans to build a tiny home to live in and transform buses into mobile salons on her new property. Weeks later, the 21-year-old hairstylist returned to find her buses vandalized with anti-Black racial slurs. Her neighbor, a white man, sat outside his home, his gun on display, his yard brandishing Ku Klux Klan signs, Confederate flags, and swastikas. "Oh, yeah, they do that all the time," Pittman, speaking to The Guardian, recalled deputies telling her of the scene. A sheriff's captain in the county told the outlet the incident was not a hate crime.

Fearing for her safety, Pittman moved back to her hometown of Charlotte. Thousands have since rallied to help her recoup her losses, raising over $118,600 in donations.

Hate crimes are defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation as a "criminal offense which is motivated, in whole or in part, by the offender's bias(es) against a person based on race, ethnicity, ancestry, religion, sexual orientation, disability, gender, and gender identity." Rates of violence against marginalized individuals vary in frequency throughout the 30 years of documented reports from the FBI. Still, according to an annual report from the bureau, one thing remains constant: Black Americans are the most targeted demographic.

According to reports and surveys from the FBI and the Department of Justice, hate crimes have largely been connected to race or ethnicity. Within this sect of reported hate crimes, Black Americans carry most of the burden. With this in mind, Stacker analyzed data from the FBI's annual Hate Crime Statistics report to chronicle how Black Americans are affected by hate crimes.

Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Last September, Angel Pittman bought land in a small town 8 miles outside Salisbury, North Carolina, with plans to build a tiny home to live in and transform buses into mobile salons on her new property. Weeks later, the 21-year-old hairstylist returned to find her buses vandalized with anti-Black racial slurs. Her neighbor, a white man, sat outside his home, his gun on display, his yard brandishing Ku Klux Klan signs, Confederate flags, and swastikas. "Oh, yeah, they do that all the time," Pittman, speaking to The Guardian, recalled deputies telling her of the scene. A sheriff's captain in the county told the outlet the incident was not a hate crime.

Fearing for her safety, Pittman moved back to her hometown of Charlotte. Thousands have since rallied to help her recoup her losses, raising over $118,600 in donations.

Hate crimes are defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation as a "criminal offense which is motivated, in whole or in part, by the offender's bias(es) against a person based on race, ethnicity, ancestry, religion, sexual orientation, disability, gender, and gender identity." Rates of violence against marginalized individuals vary in frequency throughout the 30 years of documented reports from the FBI. Still, according to an annual report from the bureau, one thing remains constant: Black Americans are the most targeted demographic.

According to reports and surveys from the FBI and the Department of Justice, hate crimes have largely been connected to race or ethnicity. Within this sect of reported hate crimes, Black Americans carry most of the burden. With this in mind, Stacker analyzed data from the FBI's annual Hate Crime Statistics report to chronicle how Black Americans are affected by hate crimes.

-

‘How do you protect a Black kid?’ Protesters demand justice in shooting of Kansas City teenager

Stacker // Jared Beilby

Hate crimes reported in 2021, the latest available data, show motivation was most commonly linked to race or ethnicity, accounting for nearly 4,500 incidents. Sexual orientation and religion—with 1,132 and 1,013 incidents, respectively—were the second and third most common biases.

This graph indicates only a fraction of hate crimes in the United States. Getting a full picture is a complicated affair. As ProPublica explains, the FBI relies on local enforcement agencies to collect and submit hate crime data, but there are no clear regulations and processes in place to do so. The nonprofit's investigation exposed communication breakdowns between local and federal agencies. Thousands of cases each year are lost in this broken system. These figures should then be at least taken as a means to determine trends and patterns.

One indication of the wide margin between reported and actual incidents lies in the discrepancy between the Department of Justice's National Crime Victimization Survey and the FBI's data. From 2005 and 2019, there were about 246,900 hate crime incidents self-reported by households annually. The FBI, however, only tallied 7,303 hate crimes in 2021—3% of that yearly average.

Stacker // Jared Beilby

Hate crimes reported in 2021, the latest available data, show motivation was most commonly linked to race or ethnicity, accounting for nearly 4,500 incidents. Sexual orientation and religion—with 1,132 and 1,013 incidents, respectively—were the second and third most common biases.

This graph indicates only a fraction of hate crimes in the United States. Getting a full picture is a complicated affair. As ProPublica explains, the FBI relies on local enforcement agencies to collect and submit hate crime data, but there are no clear regulations and processes in place to do so. The nonprofit's investigation exposed communication breakdowns between local and federal agencies. Thousands of cases each year are lost in this broken system. These figures should then be at least taken as a means to determine trends and patterns.

One indication of the wide margin between reported and actual incidents lies in the discrepancy between the Department of Justice's National Crime Victimization Survey and the FBI's data. From 2005 and 2019, there were about 246,900 hate crime incidents self-reported by households annually. The FBI, however, only tallied 7,303 hate crimes in 2021—3% of that yearly average.

-

-

‘How do you protect a Black kid?’ Protesters demand justice in shooting of Kansas City teenager

Stacker // Jared Beilby

The FBI began tracking hate crimes in 1991. More than 4,500 race-based hate crimes are reported annually—and that number has only increased.

The numbers have varied over time. There were sharp upticks for hate crimes toward Black Americans shown in 1996, the year former President Bill Clinton signed a welfare reform bill into law, sparking discussions about its supposed beneficiaries; 2008, the year after the Southern Poverty Law Center noted a staggering growth of hate groups such as neo-Nazis, skinheads, KKK, and Black separatists (which the SPLC has since collapsed to avoid drawing a false equivalency to white supremacist extremism); and 2020, when the country grappled with social upheavals amid the COVID-19 pandemic. That year, Black Americans accounted for 31% of racially motivated hate crimes reported in 2021, per FBI data.

Stacker // Jared Beilby

The FBI began tracking hate crimes in 1991. More than 4,500 race-based hate crimes are reported annually—and that number has only increased.

The numbers have varied over time. There were sharp upticks for hate crimes toward Black Americans shown in 1996, the year former President Bill Clinton signed a welfare reform bill into law, sparking discussions about its supposed beneficiaries; 2008, the year after the Southern Poverty Law Center noted a staggering growth of hate groups such as neo-Nazis, skinheads, KKK, and Black separatists (which the SPLC has since collapsed to avoid drawing a false equivalency to white supremacist extremism); and 2020, when the country grappled with social upheavals amid the COVID-19 pandemic. That year, Black Americans accounted for 31% of racially motivated hate crimes reported in 2021, per FBI data.

-

‘How do you protect a Black kid?’ Protesters demand justice in shooting of Kansas City teenager

Libby March for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Reliable hate crime data is limited, in part due to local agencies' reporting protocols and specific reporting criteria and definitions. Disparities in reporting are shown between local and federal agencies, with some even claiming to have no hate crimes in 2016.

Additionally, according to the FBI, the report collected in 2021 is the first to be compiled with data completely from the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which aims to improve the "overall quality of crime data collected by law enforcement" by capturing comprehensive information on each single crime incident as well as separate offenses within the same incident. During this transition to this system, some individual agencies and states failed to switch over to the new system in time, resulting in a lack of data for 2021. Because of this, there is a noticeable decline in reports between 2020 and 2021.

Libby March for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Reliable hate crime data is limited, in part due to local agencies' reporting protocols and specific reporting criteria and definitions. Disparities in reporting are shown between local and federal agencies, with some even claiming to have no hate crimes in 2016.

Additionally, according to the FBI, the report collected in 2021 is the first to be compiled with data completely from the National Incident-Based Reporting System, which aims to improve the "overall quality of crime data collected by law enforcement" by capturing comprehensive information on each single crime incident as well as separate offenses within the same incident. During this transition to this system, some individual agencies and states failed to switch over to the new system in time, resulting in a lack of data for 2021. Because of this, there is a noticeable decline in reports between 2020 and 2021.

-

-

‘How do you protect a Black kid?’ Protesters demand justice in shooting of Kansas City teenager

Stacker // Jared Beilby

On June 17, 2015, a group of Black churchgoers were attending Bible study at a historic Black church in Charleston, South Carolina, when white supremacist Dylann Roof—who had even sat in on the session—drew out a handgun and shot and killed nine of them. He was later convicted of 33 hate crimes and murder charges.

Roof's outspokenness about his anti-Black views—through his public website and writings from jail—and the aftermath of the massacre stirred conversations among federal lawmakers about the proposal of an anti-Black-specific hate crime bill shortly after. However, it has yet to move forward.

In 2021, Congress passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act to specifically address anti-Asian hate crimes—and rightfully so—after the increase in hate crimes targeting Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. In 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act sought to prosecute hate crimes based on sexual orientation and gender. No such bill exists regarding anti-Black hate crimes. In fact, the U.S. had no anti-lynching legislation until 2022, more than 100 years after the country's only Black member of Congress attempted to pass one in 1900.

Almost seven years after the Charleston shooting, on May 14, 2022, a white 18-year-old man named Payton Gendron traveled 3.5 hours from his hometown to Buffalo, New York, walked into a supermarket in a predominantly Black neighborhood armed with an AR-15-style rifle, and opened fire on 13 innocent shoppers, killing 10—all of whom were Black. Gendron received back-to-back life sentences without the possibility of parole for his racially motivated hate crimes.

The Buffalo tragedy hearkened back to the Charleston church massacre, reigniting demands for protections for Black Americans against such hate crimes—yet still to no avail.

Circumstances like these factor into the hesitation from victims regarding making official reports, ultimately contributing to the limitations of hate crime data.

In more than a third of cases (38%), victims surveyed said they dealt with the crime in another way rather than reporting it to the police. Almost a quarter (23%) of DOJ's survey participants who did not report hate crimes also stated they believed police would not or could not do anything to help. Other reasons for not reporting fell under the category of "not important enough," which includes victims who said it was a minor or unsuccessful crime, situations where the offender(s) was a child, or that insurance would not cover their losses.

Fear of retaliation from the offender was the third most common reason victims chose not to report.

Stacker // Jared Beilby

On June 17, 2015, a group of Black churchgoers were attending Bible study at a historic Black church in Charleston, South Carolina, when white supremacist Dylann Roof—who had even sat in on the session—drew out a handgun and shot and killed nine of them. He was later convicted of 33 hate crimes and murder charges.

Roof's outspokenness about his anti-Black views—through his public website and writings from jail—and the aftermath of the massacre stirred conversations among federal lawmakers about the proposal of an anti-Black-specific hate crime bill shortly after. However, it has yet to move forward.

In 2021, Congress passed the COVID-19 Hate Crimes Act to specifically address anti-Asian hate crimes—and rightfully so—after the increase in hate crimes targeting Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. In 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr., Hate Crimes Prevention Act sought to prosecute hate crimes based on sexual orientation and gender. No such bill exists regarding anti-Black hate crimes. In fact, the U.S. had no anti-lynching legislation until 2022, more than 100 years after the country's only Black member of Congress attempted to pass one in 1900.

Almost seven years after the Charleston shooting, on May 14, 2022, a white 18-year-old man named Payton Gendron traveled 3.5 hours from his hometown to Buffalo, New York, walked into a supermarket in a predominantly Black neighborhood armed with an AR-15-style rifle, and opened fire on 13 innocent shoppers, killing 10—all of whom were Black. Gendron received back-to-back life sentences without the possibility of parole for his racially motivated hate crimes.

The Buffalo tragedy hearkened back to the Charleston church massacre, reigniting demands for protections for Black Americans against such hate crimes—yet still to no avail.

Circumstances like these factor into the hesitation from victims regarding making official reports, ultimately contributing to the limitations of hate crime data.

In more than a third of cases (38%), victims surveyed said they dealt with the crime in another way rather than reporting it to the police. Almost a quarter (23%) of DOJ's survey participants who did not report hate crimes also stated they believed police would not or could not do anything to help. Other reasons for not reporting fell under the category of "not important enough," which includes victims who said it was a minor or unsuccessful crime, situations where the offender(s) was a child, or that insurance would not cover their losses.

Fear of retaliation from the offender was the third most common reason victims chose not to report.

-

‘How do you protect a Black kid?’ Protesters demand justice in shooting of Kansas City teenager

Eugenio Marongiu // Shutterstock

With the FBI's data set, a category of "multiple biases" exists, leaving room for additional data to show hate crimes involving Black Americans that also occupy other marginalized identities. This highlights the opportunity for explicit discussion around hate crimes that cross intersections of identity, such as misogynoir (hatred directed toward Black women) or other biases that disproportionately lead to violence against Black individuals, such as transphobia (2 in 3 victims of fatal violence against transgender and gender-nonconforming people are Black transgender women).

Even without these more nuanced approaches to the data, it is clear that despite changing economies, political landscapes, and media coverage, Black Americans' level of risk for hate crimes has prevailed. Black communities only account for 13.6% of the total U.S. population, but each year, about a third of hate crimes specifically target Black Americans. It's a devastating legacy in the U.S. that's persisted with little to no federal policy to reverse the course.

You may also like: Notable companies founded by Black entrepreneurs

Eugenio Marongiu // Shutterstock

With the FBI's data set, a category of "multiple biases" exists, leaving room for additional data to show hate crimes involving Black Americans that also occupy other marginalized identities. This highlights the opportunity for explicit discussion around hate crimes that cross intersections of identity, such as misogynoir (hatred directed toward Black women) or other biases that disproportionately lead to violence against Black individuals, such as transphobia (2 in 3 victims of fatal violence against transgender and gender-nonconforming people are Black transgender women).

Even without these more nuanced approaches to the data, it is clear that despite changing economies, political landscapes, and media coverage, Black Americans' level of risk for hate crimes has prevailed. Black communities only account for 13.6% of the total U.S. population, but each year, about a third of hate crimes specifically target Black Americans. It's a devastating legacy in the U.S. that's persisted with little to no federal policy to reverse the course.

You may also like: Notable companies founded by Black entrepreneurs