‘Too much to learn’: Schools race to catch up kids’ reading

ATLANTA — Michael Crowder stood nervously at the front of his third grade classroom, his yellow polo shirt buttoned to the top.

“Give us some vowels,” said his teacher, La’Neeka Gilbert-Jackson. His eyes searched a chart, but he didn’t land on an answer. “Let’s help him out,” Gilbert-Jackson said.

“A-E-I-O-U,” the class said in unison.

Michael missed most of first grade, the foundational year for learning to read. It was the first fall of the COVID-19 pandemic, and for months Atlanta only offered school online. Michael’s mom had just had a baby, and there was no quiet place in their small apartment. He missed part of second grade, too. So, like most of his classmates at his Atlanta school, he isn’t reading at the level expected for a third grader.

That poses an urgent problem.

Third grade is the last chance for Michael and his classmates to master reading before they face more rigorous expectations. If the students don’t read fluently by the time this school year ends, research shows they’re less likely to complete high school. Pandemic-fueled school interruptions raised the stakes: Nationally, third graders lost more ground in reading than kids in older grades.

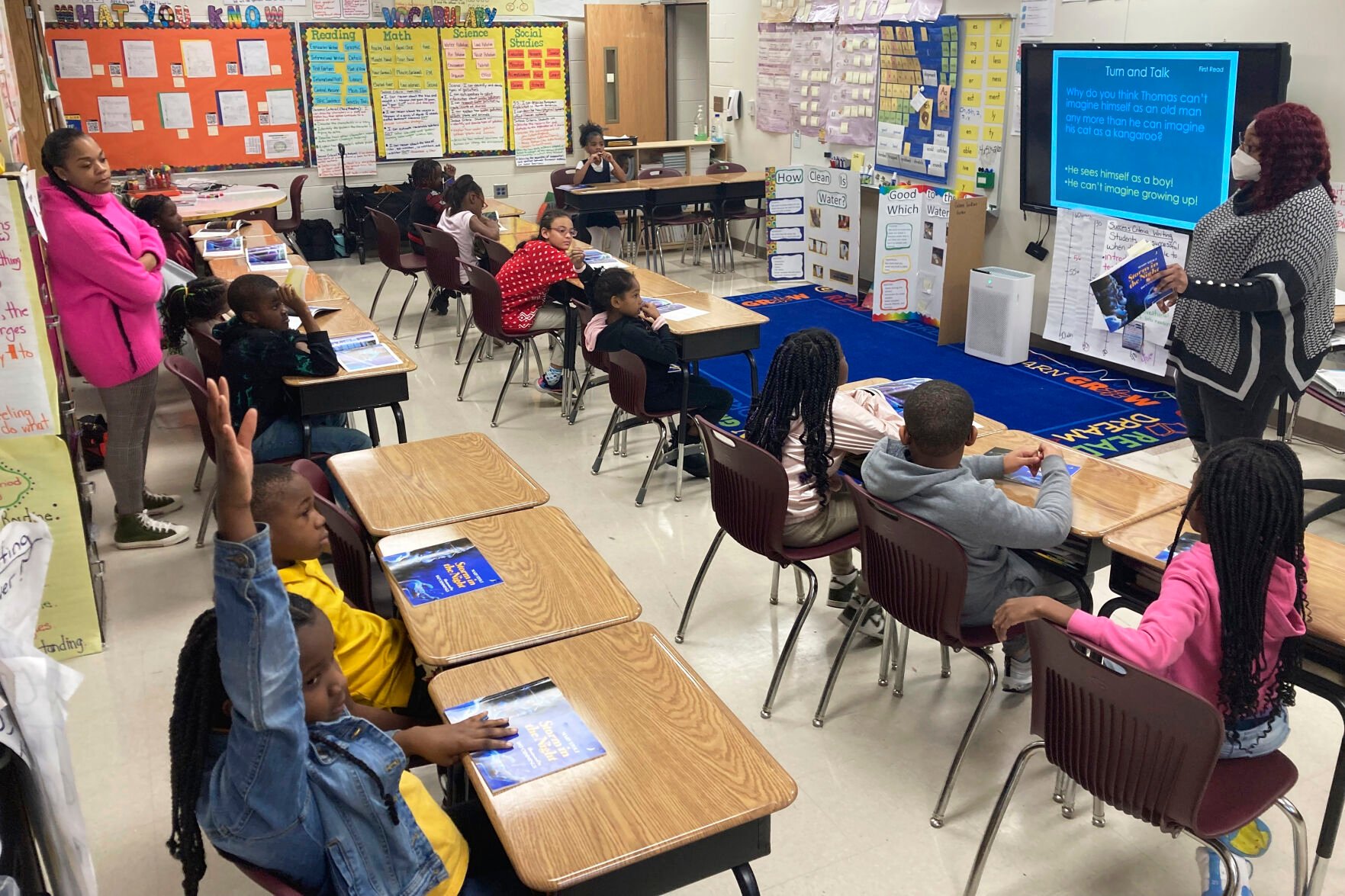

Sharon Johnson, Associated Press

Students answer questions Dec. 15, 2022, as they read a book with third grade teacher La'Neeka Gilbert-Jackson, back right, at Boyd Elementary School in Atlanta.

To address learning loss, Atlanta has been one of the only cities in the country to add class time: 30 minutes a day for three years.

Gilbert-Jackson hopes it will be enough. She has raced to prepare her students for future classes, where reading well is a gateway to everything else.

“Yes, I work you hard,” she says about her students. “Because we have too much to learn.”

Before December vacation, the class was subdued and visibly tired but Gilbert-Jackson moved on with her lessons.

She reviewed suffixes, how to spell words ending in -ch, -tch, and how to make words plural. Some students had spellings memorized; for those who don’t, Gilbert-Jackson explained the rules. It’s a phonics-based program the district now mandates for all third graders, in line with science-backed curricula gaining momentum across the country.

It can be dry and tedious, replete with obscure jargon like “digraph” and “trigraph.” The strong readers nodded and responded, but the students still learning the basics looked lost.

To inject fun into the lesson, Gilbert-Jackson turned it into a quiz game.

“Teach,” Gilbert-Jackson called out. “How do you spell teach?”

Students chose between “teach” and “teatch.” Only half got it right.

Alex Slitz, Associated Press

Michael Crowder, 11, right, reads to Tim McNeeley, left, during an after-school literacy program April 6 in Atlanta. McNeeley, director of the Atlanta-based Pure Hope Project, hosts the daily program for children in kindergarten through fifth grade.

As the first semester drew to a close, 14 of Gilbert-Jackson’s 19 students weren’t meeting expectations for reading. That included Michael.

Gilbert-Jackson has an important advantage: She taught most of her students in first grade and second grade, and followed them to third. She knows how much school many of them missed — and why. The strategy was adopted by Boyd Elementary to give students consistency through the crisis.

The long-term connection — or perhaps just the continuity of attending school daily — helped Michael start reading. At the end of first grade he knew two of the so-called “sight words” —”a” and “the.” By that point, first graders were expected to have memorized 200 of these high-frequency words.

Now, midway through third grade, he is reading like a mid-year first grader. It’s progress, Gilbert-Jackson says.

“I see a change in him,” says Michael’s stepfather, Rico Morton. “I feel like he has the potential to be someone.”

Gilbert-Jackson believes some parents were doing work for their children when school was online.

Sharon Johnson, Associated Press

Third-grade teaching assistant Keione Vance leads a reading session Dec. 15, 2022, with a small group of students at Boyd Elementary School in Atlanta.

On paper, Atlanta’ policy is to promote elementary school students who “master” reading, math and other subjects. How often the district, which did not respond to requests for data, holds students back is unclear.

Atlanta students can attend four weeks of summer school, but that likely won’t be enough to catch them up.

Gilbert-Jackson started reaching out to students’ parents to talk about how their children were progressing. The parents of some struggling readers don’t return her calls.

One day in late February, Gilbert-Jackson asked her students to revise a narrative they’d each been writing about a glowing rock.

One new student, a boy with a 100-watt smile, had transferred from another school. Instead of taking out his narrative, he chose a book from the class library and started writing. He presented his notebook to Keione Vance, the teacher’s assistant.

“I know you just copied it,” she said.

She asked him to read to her. He started on the book aimed at a first grade reading level, but struggled with words: nice, true, voice, sure, might, outside and because.

When he arrived in November, it appeared he needed “to learn everything from first, second and third grade,” Gilbert-Jackson said.

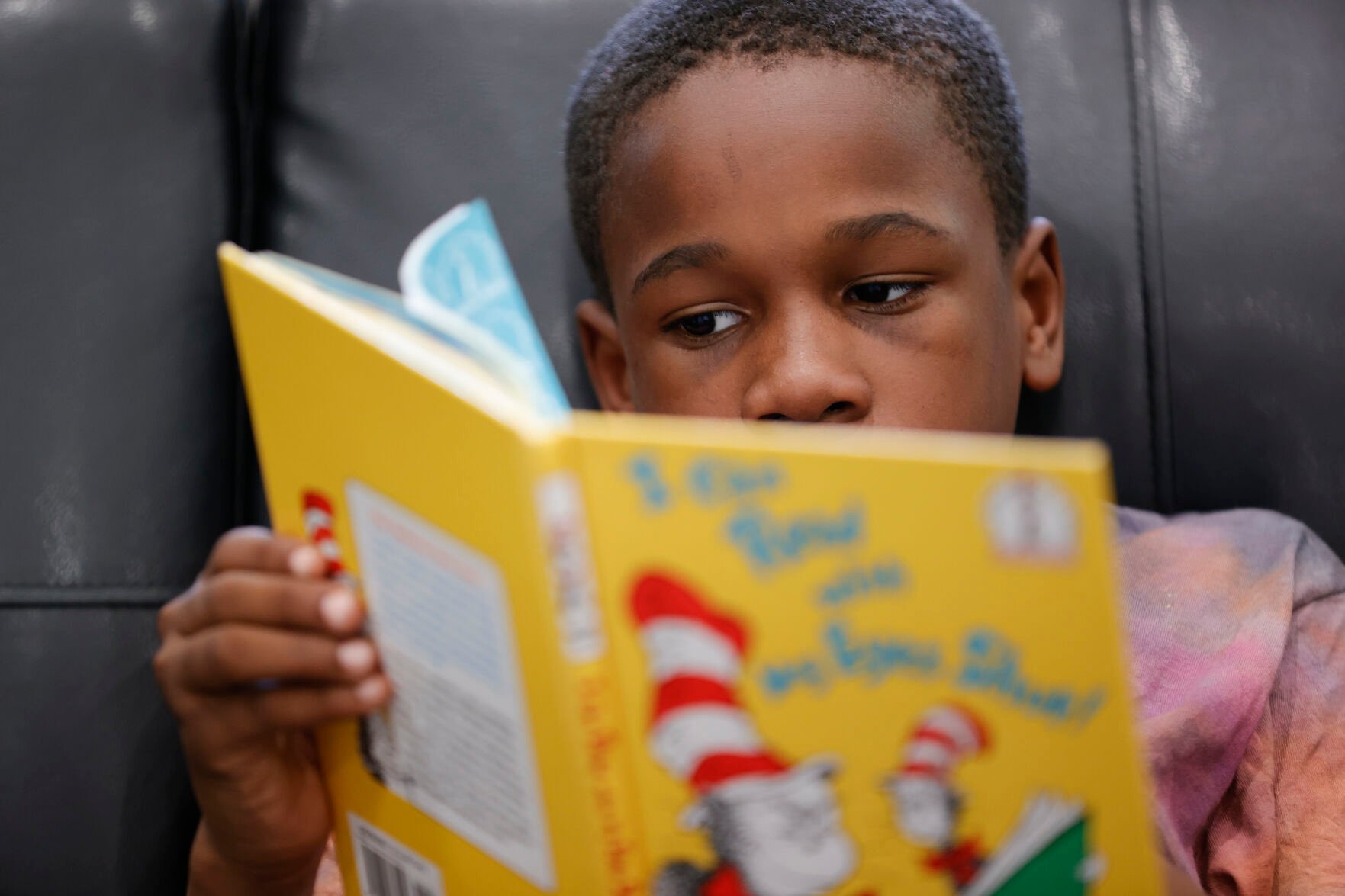

Alex Slitz, Associated Press

Michael Crowder, 11, reads during an after-school literacy program April 6 in Atlanta.

She worries she isn’t serving her new students as well as she’d like. “This train has been running for three years,” she said. “I can’t start over.”

She and the other third grade teachers were so concerned about their students’ reading and math skills, they decided after Christmas break to cut back on social studies and science.

Now only seven of the 19 students are below grade level in reading. Of those still behind, Gilbert-Jackson is the least worried about one: Michael Crowder. She’s confident he’ll find a way to navigate the new world ahead of him.

“He wants it,” she says. “He’ll catch up.”

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itGround Picture // Shutterstock

Several studies within the past year have shown just how detrimental remote learning has been to academic progress during the coronavirus pandemic, especially for students already disadvantaged by racial and economic achievement gaps.

Harvard University's Center for Education Policy Research, for example, looked at testing data from fall 2019 through fall 2021 of 2 million students in 10,000 schools across 49 states, including Washington D.C. Compared to testing data from the two years before the pandemic, its findings showed that remote learning, including hybrid models, was one of the primary causes of widening academic achievement gaps.

Remote learning is only as effective as the resources a student can access, particularly for younger kids. High-performing fourth-grade students reported having greater access to resources like a computer, a quiet place to work, and a teacher to help them compared to low-performing students, according to a separate study conducted by the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Students in homes where parental educational attainment was less than a high school diploma, as well as those from the lowest income quarter, were most likely to have home internet access only through a smartphone.

As a result of different regional COVID-19 policies and restrictions, achievement gaps varied but were most severe in states with longer durations of remote instruction. Additionally, schools made up of a high percentage of students from low-income families spent an extra 5.5 weeks, on average, learning remotely during 2020-21 than wealthier schools, and fell further behind because of it. While achievement losses still persist among schools that went back to in-person learning, achievement gaps were not worsened like they were among remote students.

The NAEP analyzes exams administered by the Department of Education to fourth and eighth graders as a common measure of academic achievement across the country in math and reading, among other subjects. Its 2022 analysis found that performance decreased across the board. Nationally, average fourth-grade math scores fell five points since 2019, while eighth-grade math scores dropped eight points. Average reading scores for both fourth and eighth grades fell three points.

To put the 20-year math and reading lows into context, HeyTutor analyzed the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress data from the DOE's National Center for Education Statistics.

Although school districts are only required to allocate 20% of their American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding to academic recovery efforts, the Harvard study concludes that some will need to spend all of their aid to combat the effects of lost instructional time and close the achievement gap widened by remote learning.

Ground Picture // Shutterstock

Ground Picture // ShutterstockSeveral studies within the past year have shown just how detrimental remote learning has been to academic progress during the coronavirus pandemic, especially for students already disadvantaged by racial and economic achievement gaps.

Harvard University's Center for Education Policy Research, for example, looked at testing data from fall 2019 through fall 2021 of 2 million students in 10,000 schools across 49 states, including Washington D.C. Compared to testing data from the two years before the pandemic, its findings showed that remote learning, including hybrid models, was one of the primary causes of widening academic achievement gaps.

Remote learning is only as effective as the resources a student can access, particularly for younger kids. High-performing fourth-grade students reported having greater access to resources like a computer, a quiet place to work, and a teacher to help them compared to low-performing students, according to a separate study conducted by the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Students in homes where parental educational attainment was less than a high school diploma, as well as those from the lowest income quarter, were most likely to have home internet access only through a smartphone.

As a result of different regional COVID-19 policies and restrictions, achievement gaps varied but were most severe in states with longer durations of remote instruction. Additionally, schools made up of a high percentage of students from low-income families spent an extra 5.5 weeks, on average, learning remotely during 2020-21 than wealthier schools, and fell further behind because of it. While achievement losses still persist among schools that went back to in-person learning, achievement gaps were not worsened like they were among remote students.

The NAEP analyzes exams administered by the Department of Education to fourth and eighth graders as a common measure of academic achievement across the country in math and reading, among other subjects. Its 2022 analysis found that performance decreased across the board. Nationally, average fourth-grade math scores fell five points since 2019, while eighth-grade math scores dropped eight points. Average reading scores for both fourth and eighth grades fell three points.

To put the 20-year math and reading lows into context, HeyTutor analyzed the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress data from the DOE's National Center for Education Statistics.

Although school districts are only required to allocate 20% of their American Rescue Plan Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funding to academic recovery efforts, the Harvard study concludes that some will need to spend all of their aid to combat the effects of lost instructional time and close the achievement gap widened by remote learning.

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 230 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 59% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 213 (6-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 53% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 251 (2-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 230 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 59% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 213 (6-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 53% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 251 (2-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itMarc Cappelletti // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 65% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 226 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 51% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 204 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 59% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 253 (3-point decrease from 2003)

Marc Cappelletti // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 65% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 226 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 51% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 204 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 59% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 253 (3-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itBrandon Burris // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 232 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (6-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 271 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (4-point increase from 2003)

Brandon Burris // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 232 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (6-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 271 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (4-point increase from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itTrong Nguyen // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 228 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 55% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 267 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 255 (3-point decrease from 2003)

Trong Nguyen // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 228 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 55% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 267 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 255 (3-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 230 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (8-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 56% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (8-point increase from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 230 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (8-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 56% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (8-point increase from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 63% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 275 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 263 (5-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 63% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 275 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 263 (5-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 63% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (3-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 63% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (3-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 64% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 226 (10-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 53% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 208 (16-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 51% at basic level, 18% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (13-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 253 (12-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 64% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 226 (10-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 53% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 208 (16-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 51% at basic level, 18% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (13-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 253 (12-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itFotosForTheFuture // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 81% at basic level, 41% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 241 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 39% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 225 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 271 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (3-point increase from 2003)

FotosForTheFuture // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 81% at basic level, 41% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 241 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 39% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 225 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 271 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (3-point increase from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itESB Professional // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 235 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 216 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 59% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 271 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (2-point increase from 2003)

ESB Professional // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 235 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 216 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 59% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 271 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (2-point increase from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 77% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 237 (10-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (11-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (8-point increase from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 77% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 237 (10-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (11-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (8-point increase from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 282 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 74% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (no change from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 282 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 74% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (no change from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itDiegoMariottini // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 237 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 62% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 275 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (4-point decrease from 2003)

DiegoMariottini // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 237 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 62% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 275 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (4-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 261 (4-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 261 (4-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 277 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (8-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 277 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (8-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 235 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 272 (12-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 256 (10-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 235 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 272 (12-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 256 (10-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 57% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (8-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 57% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (8-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 53% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 266 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 257 (4-point increase from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (7-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 53% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 266 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 257 (4-point increase from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 233 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 213 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 273 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 257 (11-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 233 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 213 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 273 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 257 (11-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get iteurobanks // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 65% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 56% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 54% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (3-point decrease from 2003)

eurobanks // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 65% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 56% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 54% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (3-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 79% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 242 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 227 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 284 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 77% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (4-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 79% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 242 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 227 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 284 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 77% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (4-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 232 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 273 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (5-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 232 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 273 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (5-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 41% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 280 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (8-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 41% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 215 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 280 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (8-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (11-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (12-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 54% at basic level, 18% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 266 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 253 (2-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (11-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (12-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 54% at basic level, 18% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 266 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 253 (2-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itPaul Brady Photography // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 72% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 232 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 213 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 272 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (9-point decrease from 2003)

Paul Brady Photography // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 72% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 232 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 213 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 272 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (9-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 68% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 277 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 261 (9-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 68% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 277 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 261 (9-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 242 (6-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (7-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 242 (6-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (7-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itJacob Boomsma // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 56% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (7-point increase from 2003)

Jacob Boomsma // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 212 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 56% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (7-point increase from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 263 (8-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 263 (8-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itf11photo // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 77% at basic level, 39% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 77% at basic level, 42% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (2-point increase from 2003)

f11photo // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 77% at basic level, 39% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 77% at basic level, 42% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (2-point increase from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itturtix // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 221 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 48% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 202 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 45% at basic level, 13% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 18% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 248 (4-point decrease from 2003)

turtix // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 19% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 221 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 48% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 202 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 45% at basic level, 13% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 18% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 248 (4-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itGagliardiPhotography // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 227 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 274 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (3-point decrease from 2003)

GagliardiPhotography // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 227 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 274 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 70% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (3-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 216 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 274 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 256 (6-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 216 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 274 (7-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 256 (6-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 81% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 278 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (12-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 81% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 69% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 278 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (12-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 238 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 64% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (5-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 238 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 64% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (5-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itTLF Images // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 55% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 208 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 52% at basic level, 16% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 251 (11-point decrease from 2003)

TLF Images // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 71% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 229 (no change from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 55% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 208 (6-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 52% at basic level, 16% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 21% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 251 (11-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 228 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 56% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 210 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 57% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 257 (7-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 29% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 228 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 56% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 210 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 57% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 257 (7-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itSean Pavone // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 238 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 62% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 274 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (5-point decrease from 2003)

Sean Pavone // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 238 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 64% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 219 (no change from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 62% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 274 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (5-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itRamunas Bruzas // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (2-point decrease from 2003)

Ramunas Bruzas // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 58% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 270 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 68% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 259 (2-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itPQK // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 216 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 56% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 254 (4-point decrease from 2003)

PQK // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (2-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 216 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 56% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 269 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 254 (4-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itHank Shiffman // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 72% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (8-point decrease from 2003)

Hank Shiffman // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 80% at basic level, 40% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 65% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 218 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 72% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (8-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itNolichuckyjake // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (8-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 59% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 272 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (no change from 2003)

Nolichuckyjake // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 76% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (8-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 59% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 60% at basic level, 25% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 272 (4-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 258 (no change from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itRoschetzky Photography // Shutterstock

- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 273 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 255 (4-point decrease from 2003)

Roschetzky Photography // Shutterstock- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 239 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 58% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (1-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 61% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 273 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 66% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 255 (4-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 42% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 221 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 282 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 75% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 265 (1-point increase from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 78% at basic level, 42% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (5-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 67% at basic level, 37% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 221 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 282 (1-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 75% at basic level, 36% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 265 (1-point increase from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (10-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (7-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 234 (8-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 62% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 66% at basic level, 27% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (10-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 73% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 264 (7-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 65% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (8-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 75% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 236 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 214 (9-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 65% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 279 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 69% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (8-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 235 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 64% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (2-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 74% at basic level, 35% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 235 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 61% at basic level, 34% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 64% at basic level, 28% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 276 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (2-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 57% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (18-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 50% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 207 (19-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 46% at basic level, 16% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (17-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 250 (11-point increase from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 57% at basic level, 24% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 223 (18-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 50% at basic level, 26% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 207 (19-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 46% at basic level, 16% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (17-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 57% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 250 (11-point increase from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 226 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 52% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 205 (14-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 48% at basic level, 15% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 249 (11-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 67% at basic level, 23% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 226 (5-point decrease from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 52% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 205 (14-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 48% at basic level, 15% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 260 (11-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 60% at basic level, 22% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 249 (11-point decrease from 2003)

-

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 79% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (4-point decrease from 2003)

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 79% at basic level, 43% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 240 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 63% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 217 (4-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 70% at basic level, 33% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 72% at basic level, 32% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 262 (4-point decrease from 2003)

-

Many kids need tutoring help. Only a small fraction get itCanva

- 4th-grade math:

--- 84% at basic level, 44% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 243 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 225 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 72% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 261 (6-point decrease from 2003)

This story originally appeared on HeyTutor and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.

Canva- 4th-grade math:

--- 84% at basic level, 44% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 243 (2-point increase from 2003)

- 4th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 38% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 225 (3-point increase from 2003)

- 8th-grade math:

--- 72% at basic level, 31% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 281 (3-point decrease from 2003)

- 8th-grade reading:

--- 71% at basic level, 30% proficient

--- 2022 average score: 261 (6-point decrease from 2003)

This story originally appeared on HeyTutor and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.