BAZHOU, China — Yao Ruyan paced frantically outside the fever clinic of a county hospital in China’s industrial Hebei province, 43 miles southwest of Beijing. Her mother-in-law had COVID-19 and needed urgent medical care but all hospitals nearby were full.

“They say there’s no beds here,” she barked into her phone.

As China grapples with a national COVID-19 wave, emergency wards in small cities and towns southwest of Beijing are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, relatives of sick people are searching for open beds and patients are slumped on benches in hospital corridors and lying on floors for a lack of beds.

Associated Press

A sick patient is moved onto a gurney Dec. 22 at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province.

Yao’s elderly mother-in-law had fallen ill a week prior. They went first to a local hospital, where lung scans showed signs of pneumonia. But the hospital couldn’t handle COVID-19 cases, Yao was told. She was told to go to hospitals in adjacent counties.

As Yao and her husband drove from hospital to hospital, they found all the wards were full. Zhuozhou Hospital, an hour’s drive from Yao’s hometown, was the latest disappointment.

“I’m furious,” Yao said, tearing up, as she clutched the lung scans from the local hospital. “I don’t have much hope. We’ve been out for a long time and I’m terrified because she’s having difficulty breathing.”

Over two days, Associated Press journalists visited five hospitals and two crematoriums in towns and small cities in Baoding and Langfang prefectures, in central Hebei province. The area was the epicenter of one of China’s first outbreaks after the state loosened COVID-19 controls in November and December.

Today, markets are bustling, diners pack restaurants and cars are honking in snarled traffic, even as the coronavirus is spreading in other parts of China. In recent days, headlines in state media said the area is “starting to resume normal life.”

But life in central Hebei’s emergency wards and crematoriums is anything but normal. Even as the young go back to work and lines at fever clinics shrink, many of Hebei’s elderly are falling into critical condition. It could be a harbinger for the rest of China.

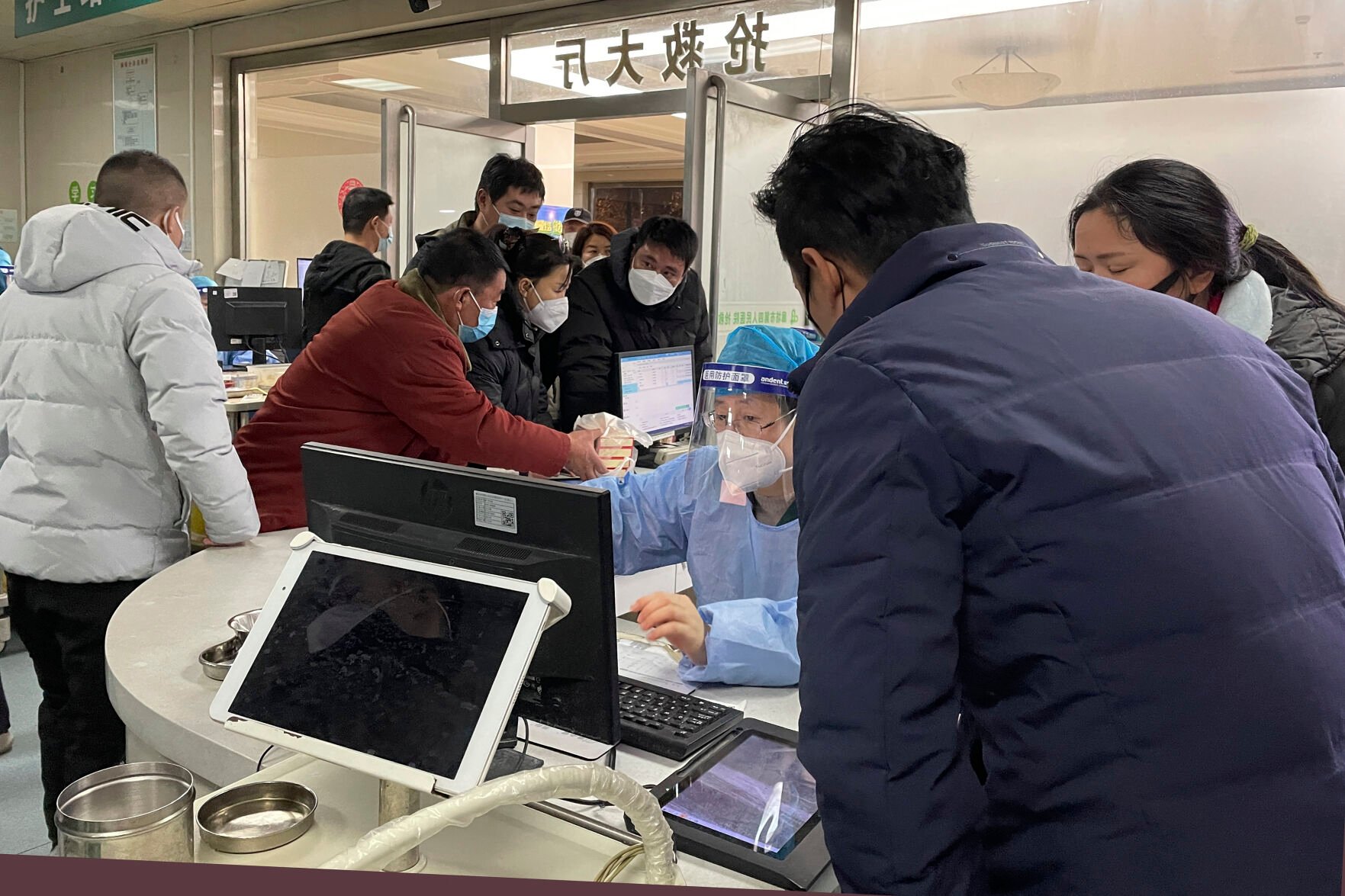

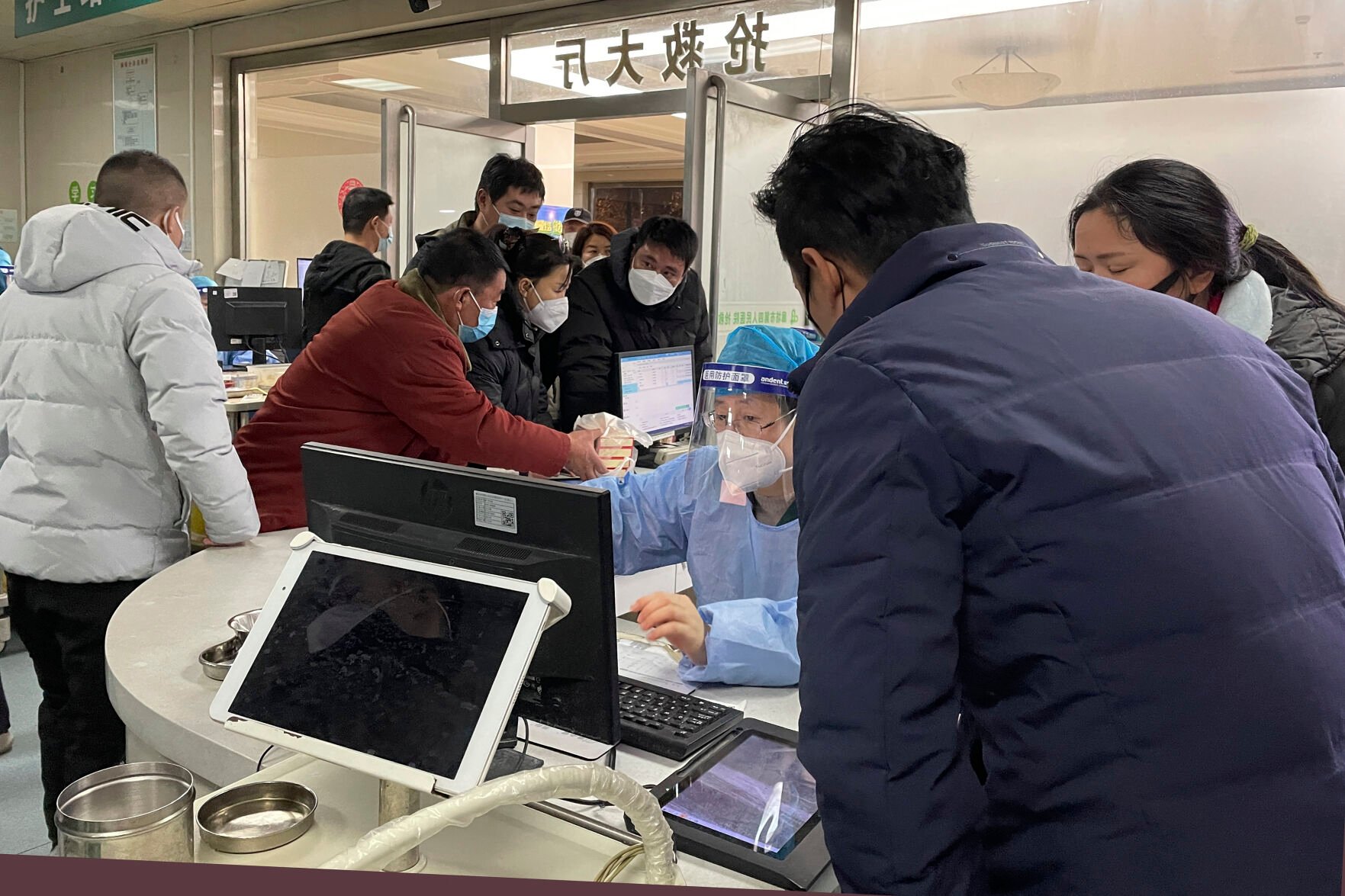

Associated Press

A worker in protective gear attends to visitors Dec. 22 at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province.

The Chinese government reported only seven COVID-19 deaths since restrictions were loosened dramatically on Dec. 7, bringing the country’s total toll to 5,241. On Tuesday, a Chinese health official said that China only counts deaths from pneumonia or respiratory failure in its official COVID-19 death toll.

Experts have forecast between a million and 2 million deaths in China next year, and the World Health Organization warned that Beijing’s way of counting would “underestimate the true death toll.”

At Baoding No. 2 Hospital in Zhuozhou on Wednesday, patients thronged the hallway of the emergency ward. The sick were breathing with the help of respirators. One woman wailed after doctors told her that a loved one died.

Associated Press

Relatives carry paper offerings Dec. 22 to burn for their dead relative at the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province.

At the Zhuozhou crematorium, furnaces are burning overtime as workers struggle to cope with a spike in deaths, according to one employee. A funeral shop worker estimated it is burning 20 to 30 bodies a day, up from three to four before COVID-19 measures were loosened.

“There’s been so many people dying,” said Zhao Yongsheng, a worker at a funeral goods shop near a local hospital. “They work day and night, but they can’t burn them all.”

Over two hours at the Gaobeidian crematorium on Thursday, AP journalists observed three ambulances and two vans unload bodies.

“There’s been a lot!” a worker said when asked about the number of COVID-19 deaths, before funeral director Ma Xiaowei stepped in and brought the journalists to meet a local government official.

As the official listened in, Ma confirmed there were more cremations but said he didn’t know if COVID-19 was involved. He blamed the extra deaths on the arrival of winter.

Associated Press

A worker in protective gear on Dec. 22 disinfects the ward of an emergency department of Baigou New Area Aerospace Hospital in Baigou in northern China's Hebei province.

But even as anecdotal evidence and modeling suggests large numbers of people are getting infected and dying, some Hebei officials deny the virus has had much impact.

“There’s no so-called explosion in cases, it’s all under control,” said Wang Ping, the administrative manager of Gaobeidian Hospital.

Wang said only a sixth of the hospital’s 600 beds were occupied, but refused to allow AP journalists to enter. Two ambulances arrived in the half hour AP journalists were present, and a patient’s relative told the AP they were turned away from Gaobeidian’s emergency ward because it was full.

In Bazhou, east of Gaobeidian, a hundred or more people packed the emergency ward of Langfang No. 4 People’s Hospital on Thursday night.

With no space in the ward, patients spilled into corridors and hallways. Sick people sprawled on blankets on the floor as staff frantically wheeled gurneys and ventilators. In a hallway, half a dozen patients wheezed on metal benches as oxygen tanks pumped air into their noses.

Over two hours, AP journalists witnessed half a dozen or more ambulances pull up to the hospital’s ER and load critical patients to sprint to other hospitals, even as cars pulled up with dozens of new patients.

Relatives surrounding a bed began tearing up as an elderly woman’s vitals flatlined. A man tugged a cloth over the woman’s face, and they stood silently before her body was wheeled away. Within minutes, another patient had taken her place.

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Andy Wong - staff, AP

FILE - Masked commuters walk through a walkway in between two subway stations as they head to work during the morning rush hour in Beijing, Tuesday, Dec. 20, 2022. China continues to adapt to an easing of strict virus containment regulations. About three years ago, the original version of the coronavirus spread from China to the rest of the world and was eventually replaced by the delta variant, then omicron and its descendants, which continue plaguing the world today.

Andy Wong - staff, AP

FILE - Masked commuters walk through a walkway in between two subway stations as they head to work during the morning rush hour in Beijing, Tuesday, Dec. 20, 2022. China continues to adapt to an easing of strict virus containment regulations. About three years ago, the original version of the coronavirus spread from China to the rest of the world and was eventually replaced by the delta variant, then omicron and its descendants, which continue plaguing the world today.

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

A man lifts an empty casket onto a van as relatives in traditional Chinese funeral attires rest near the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

Uncredited - staff, AP

A man lifts an empty casket onto a van as relatives in traditional Chinese funeral attires rest near the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

-

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

A relative in traditional Chinese funeral attire stands near funeral wreaths at the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

Uncredited - staff, AP

A relative in traditional Chinese funeral attire stands near funeral wreaths at the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

Relatives burn paper offerings for their dead relative at the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

Uncredited - staff, AP

Relatives burn paper offerings for their dead relative at the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

-

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

Family members light fireworks as offerings for their deceased relative at the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022 Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away, are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

Uncredited - staff, AP

Family members light fireworks as offerings for their deceased relative at the Gaobeidian Funeral Home in northern China's Hebei province, Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022 Bodies from Beijing, a two-hour drive away, are appearing at the Gaobeidian funeral home, because similar funeral homes in Beijing were packed.

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

Visitors to the Baigou New Area Aerospace Hospital stand near the words "Emergency Clinic" in Baigou, in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Uncredited - staff, AP

Visitors to the Baigou New Area Aerospace Hospital stand near the words "Emergency Clinic" in Baigou, in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

-

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

A hospital worker in protective gear disinfects the ward of an emergency department of Baigou New Area Aerospace Hospital in Baigou in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Uncredited - staff, AP

A hospital worker in protective gear disinfects the ward of an emergency department of Baigou New Area Aerospace Hospital in Baigou in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Dake Kang - staff, AP

A patient rests in a wheelchair at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Dake Kang - staff, AP

A patient rests in a wheelchair at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

-

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Dake Kang - staff, AP

Relatives gather near the beds of sickened patients at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Dake Kang - staff, AP

Relatives gather near the beds of sickened patients at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

A hospital worker prepares to perform tests after placing electrodes to the chest of a man sprawled out on a stretcher outside the emergency ward at the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Uncredited - staff, AP

A hospital worker prepares to perform tests after placing electrodes to the chest of a man sprawled out on a stretcher outside the emergency ward at the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

-

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

A sickened patient is moved onto a gurney at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Uncredited - staff, AP

A sickened patient is moved onto a gurney at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Dake Kang - staff, AP

Relatives attend to a sickened patient in a wheelchair at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Dake Kang - staff, AP

Relatives attend to a sickened patient in a wheelchair at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

-

-

Rapid rise of COVID-19 in China raises threat of new mutant

Uncredited - staff, AP

An ambulance prepares to transfer a patient in critical care to other hospitals due to overcapacity at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.

Uncredited - staff, AP

An ambulance prepares to transfer a patient in critical care to other hospitals due to overcapacity at the emergency department of the Langfang No. 4 People's Hospital in Bazhou city in northern China's Hebei province on Thursday, Dec. 22, 2022. As China grapples with its first-ever wave of COVID mass infections, emergency wards in the towns and cities to Beijing's southwest are overwhelmed. Intensive care units are turning away ambulances, residents are driving sick relatives from hospital to hospital, and patients are lying on floors for a lack of space.