NEW YORK — Chris Christie, one of the only 2016 presidential candidates to seriously consider taking on Donald Trump again, says he and his fellow Republican rivals made a strategic error in that race.

Instead of going after Trump directly, Christie said, each hoped to winnow the GOP field before taking on the combative outsider.

“None of us ever got there,” the former New Jersey governor said. “It was over quick.”

Mark J. Terrill, Associated Press

From left, Ohio Gov. John Kasich, former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee, former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., Donald Trump and Ben Carson participate in a debate for Republican presidential hopefuls Oct. 28, 2015, in Boulder, Colo.

More than seven years later, Republicans are still trying to figure out how to run against Trump, a calculation that’s only become more complicated with an indictment of the former president by a Manhattan grand jury.

Trump’s unrestrained and norm-busting style carried him from reality TV to the White House, transforming the Republican Party in his image along the way. But his style has befuddled those who try to compete against him, especially now as they seek to win over some of his supporters rather than draw their ire.

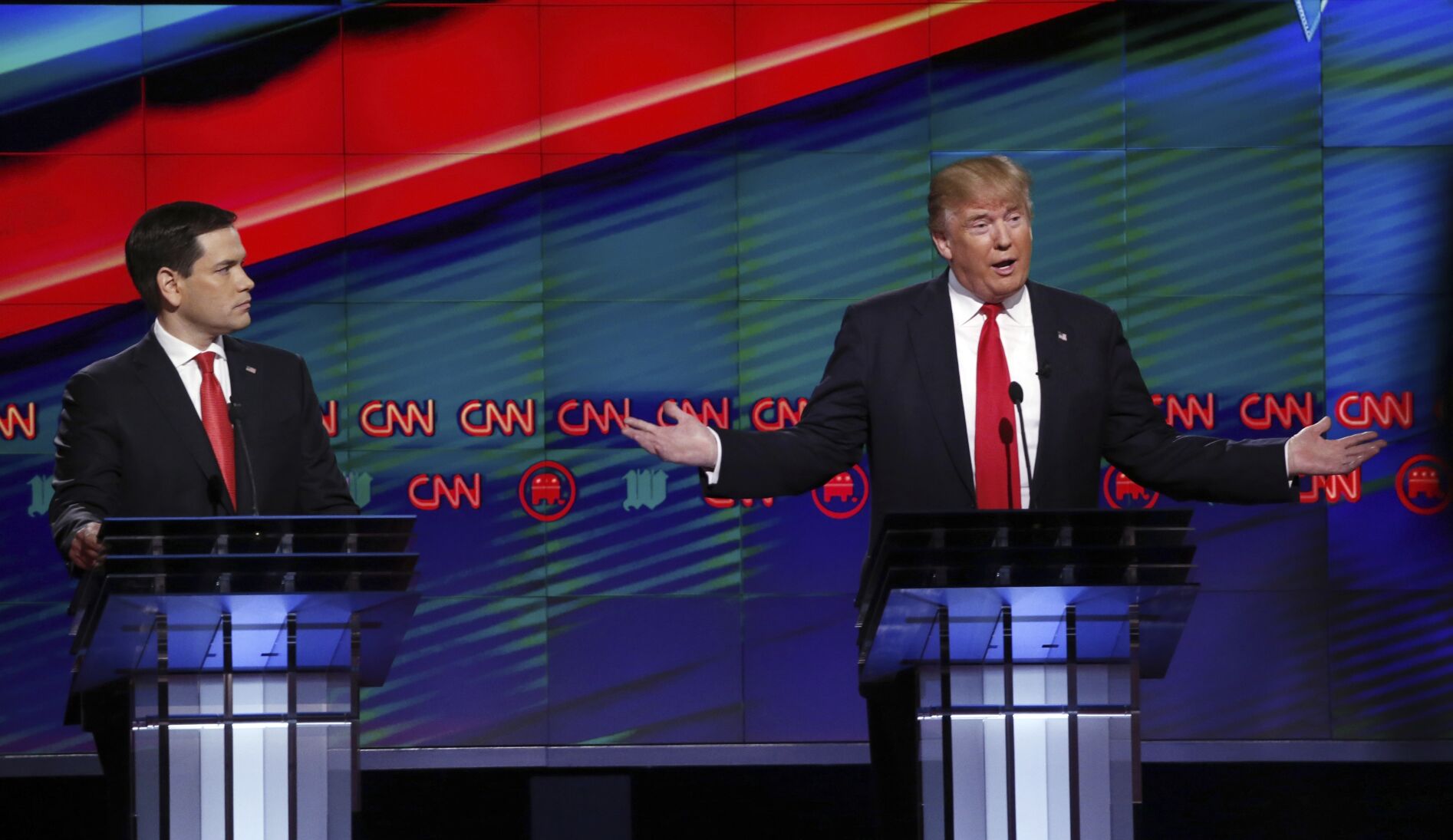

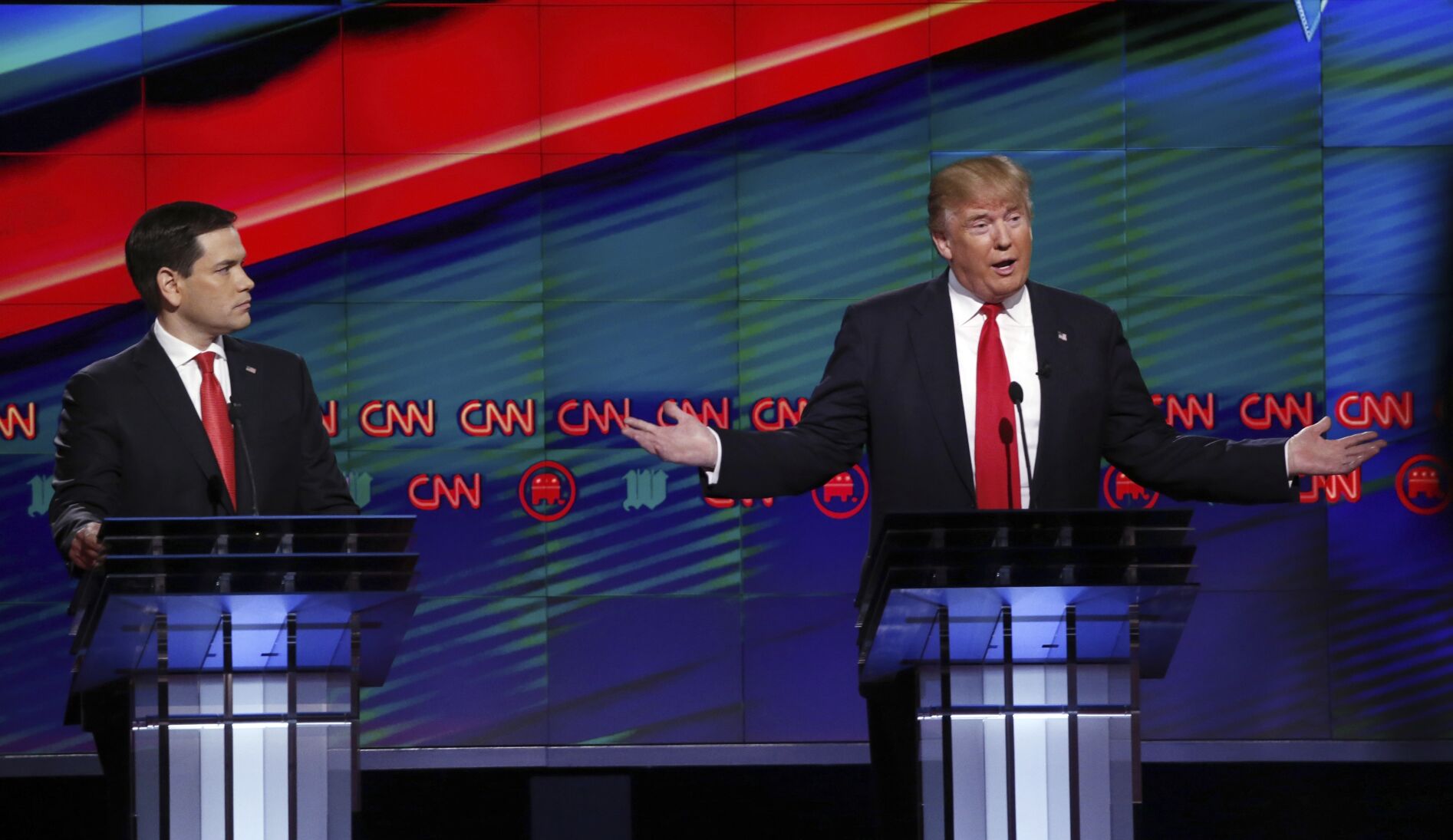

Some in 2016 tried to ignore Trump, like former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, who treated the celebrity businessman like a sideshow. Some tried to figuratively wrestle with him in the mud, like Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, who traded insults with Trump by mocking his hair and the size of his hands.

Wilfredo Lee, Associated Press

Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump, right, answers a question, as Republican presidential candidate, Sen. Marco Rubio, R-Fla., listens, during the Republican presidential debate at the University of Miami on March 10, 2016, in Coral Gables, Fla.

Neither approach worked.

“I think most politicians are not used to playing the game in such a pugilistic fashion as Trump and not as good at it,” said Jason Roe, a Michigan-based Republican political strategist.

As the 2024 field takes shape, candidates and potential contenders are struggling with how to make the case that the party needs to move on from Trump without alienating his influential “Make America Great Again” loyalists.

Trump is still considered the GOP front-runner despite facing a criminal indictment, being the subject of several other investigations, spreading false claims about his 2020 election defeat and inciting the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, among other things.

Most of Trump’s rivals or those who are eyeing a 2024 campaign have largely avoided talking about those scandals, instead opting for more shrouded criticism. Even with Trump becoming the first former president to be charged with a crime, most of his GOP rivals were quick to echo Trump’s complaint that the case is politically motivated.

Few, however, addressed the allegations related to Trump’s role in payments made during his 2016 presidential campaign to silence claims of extramarital sexual encounters. Trump has denied the allegations and proclaimed his innocence.

One notable exception is former Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson, who has been critical of Trump in recent months and announced in an interview on ABC’s “This Week” that he’s running for president. Hutchinson said Trump should drop out and focus on his legal troubles, calling them “too much of a sideshow and a distraction.”

Hutchinson, who considers himself part of the evangelical community that makes up a key bloc of the Republican electorate, said all of the serious investigations Trump is facing “should give Americans pause.”

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who is widely expected to announce a campaign and is seen as Trump’s top rival, accused prosecutors of stretching the law to target an opponent. But his remarks came a week after DeSantis took a shot at the tawdry circumstances underlying the case when asked to comment on it.

“I don’t know what goes into paying hush money to a porn star to secure silence over some type of alleged affair,” DeSantis said.

In an interview with Piers Morgan that aired a few days later, DeSantis lobbed a few subdued critiques about Trump’s leadership style but tried to brush off Trump’s repeated insults.

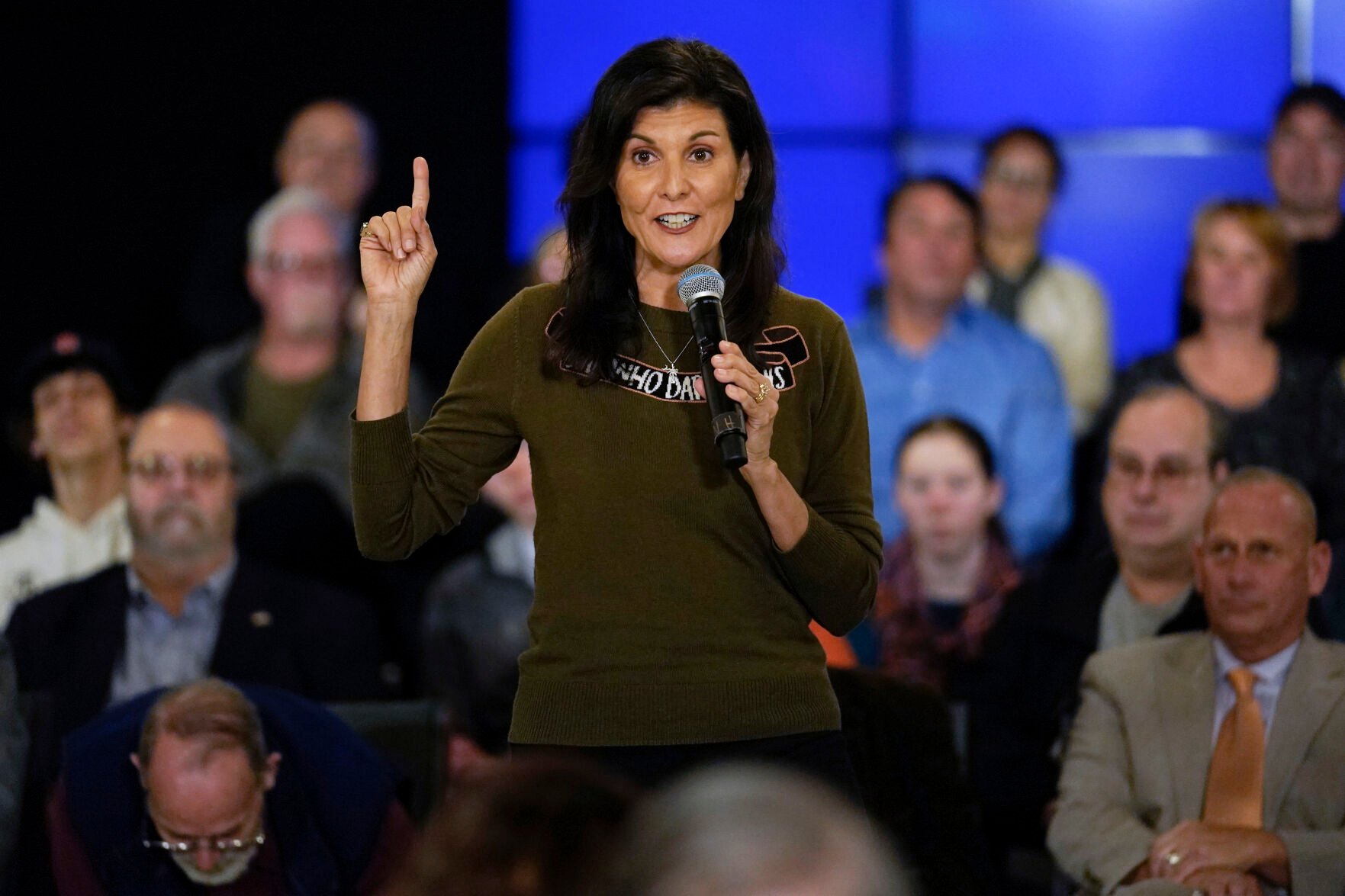

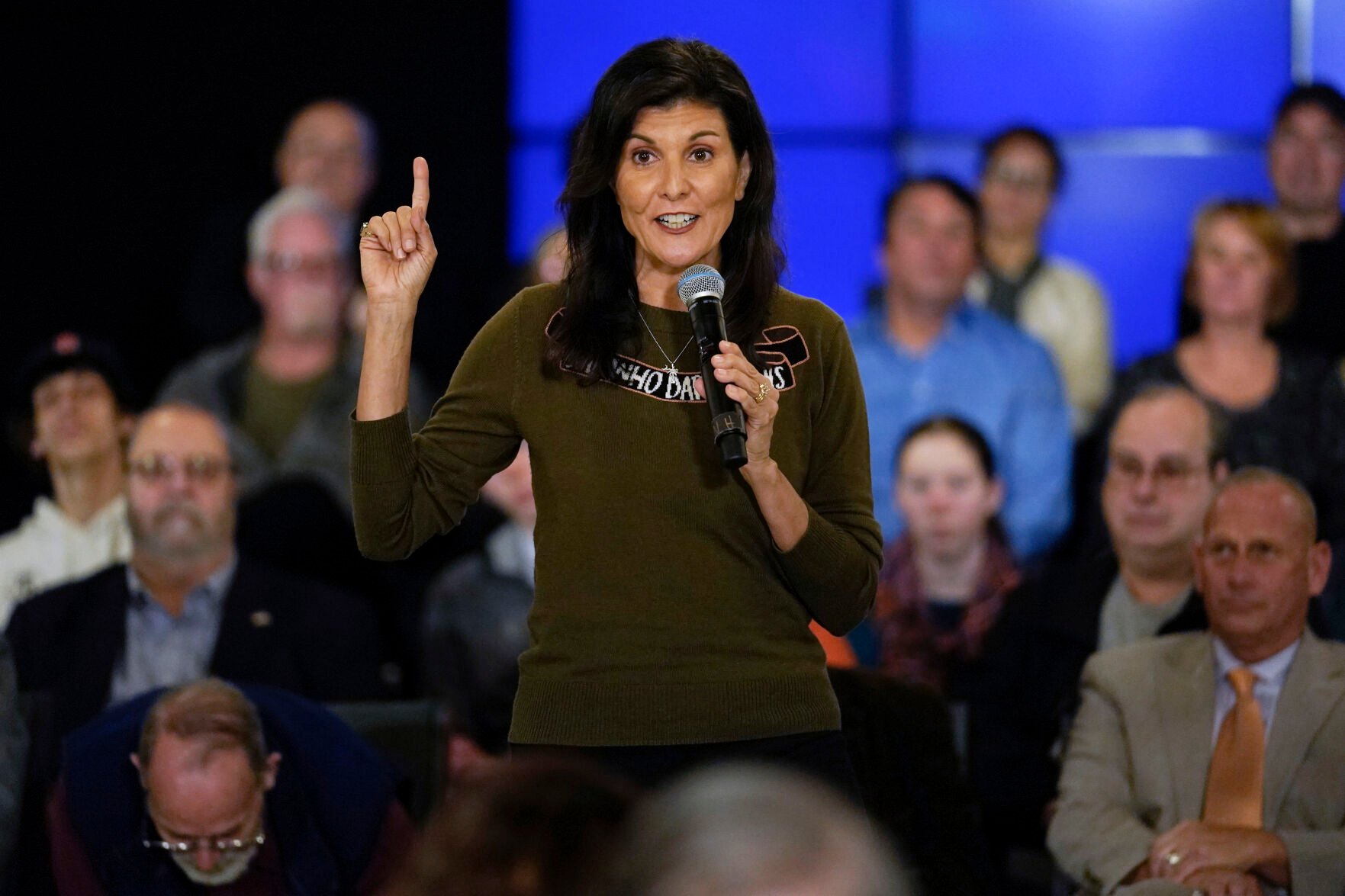

Charles Krupa, Associated Press

Republican presidential candidate, former ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley during a campaign stop March 27 in Dover, N.H.

Former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, who launched her campaign in February, and former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who is considering a presidential run, both avoided criticizing Trump by name in speeches last month at a conservative gathering and instead noted how the GOP had lost so many elections in recent years.

Haley told the crowd, “If you’re tired of losing, then put your trust in a new generation,” a remark seen as a jab at the 76-year-old Trump. Pompeo said Republicans cannot follow “celebrity leaders with their own brand of identity politics, those with fragile egos who refuse to acknowledge reality.”

Those tactics are what Roe said might be the best strategy to run against Trump — mocking his electoral performance rather than getting into a slugfest.

Roe, speaking shortly before news of Trump’s indictment broke, said the case and Trump’s reaction to it had already “sucked up all the oxygen.”

“I don’t think it pays off getting into a fight with him now,” he said.

That seems to be the calculus for Trump’s former vice president, Mike Pence. He has mostly taken a softer approach with Trump despite having to flee to safety as Trump’s supporters stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 and some in the crowd chanted, “Hang Mike Pence!”

Pence, who is now considering his own presidential campaign, has made limited criticism of Trump and reserved his sharpest comments for an untelevised speech in Washington to politicians and journalists.

Speaking last month at the white-tie Gridiron Dinner, Pence said Trump was “wrong” on Jan. 6 and his “reckless words endangered my family and everyone at the Capitol.”

But after news of Trump’s indictment broke, Pence repeatedly called the case an outrage.

If there’s one lesson from 2016, it’s that Trump’s Republican rivals can “get so preoccupied with trying to trade blows him that they don’t realize that they’re taking mortal punches,” Roe said. “And he gets stronger in that environment.”

-

Among 160 years of presidential scandals, Trump stands alone

AP Photo/Doug Mills, File

Clinton spent more than half his presidency under scrutiny in investigations that ranged from failed real estate deals to the Democratic president's affair with a White House intern.

Investigators took a lengthy look into Bill and Hillary Clinton's investments in the troubled Whitewater real estate venture. Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr, appointed to oversee the investigation in 1994, turned up no evidence of wrongdoing by the Clintons. But two of their close associates, Jim and Susan McDougal, ended up convicted of Whitewater-related charges. So did Jim Guy Tucker, Clinton's successor as governor of Arkansas.

Starr's 1998 report packed with lurid details of Clinton's affair with intern Monica Lewinsky proved far more damaging. While being questioned in a sexual harassment lawsuit filed by former Arkansas state employee Paula Jones, Clinton had denied having "sexual relations" with Lewinsky.

Starr concluded that Clinton had lied under oath and obstructed justice. That led to the House voting to impeach Clinton on Dec. 19, 1998. He was acquitted by the Senate, allowing him to remain in office until his term ended in January 2001.

AP Photo/Doug Mills, File

Clinton spent more than half his presidency under scrutiny in investigations that ranged from failed real estate deals to the Democratic president's affair with a White House intern.

Investigators took a lengthy look into Bill and Hillary Clinton's investments in the troubled Whitewater real estate venture. Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr, appointed to oversee the investigation in 1994, turned up no evidence of wrongdoing by the Clintons. But two of their close associates, Jim and Susan McDougal, ended up convicted of Whitewater-related charges. So did Jim Guy Tucker, Clinton's successor as governor of Arkansas.

Starr's 1998 report packed with lurid details of Clinton's affair with intern Monica Lewinsky proved far more damaging. While being questioned in a sexual harassment lawsuit filed by former Arkansas state employee Paula Jones, Clinton had denied having "sexual relations" with Lewinsky.

Starr concluded that Clinton had lied under oath and obstructed justice. That led to the House voting to impeach Clinton on Dec. 19, 1998. He was acquitted by the Senate, allowing him to remain in office until his term ended in January 2001.

-

Among 160 years of presidential scandals, Trump stands alone

AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File

Reagan never faced impeachment or court charges for the biggest scandal of his presidency. But the arms-for-hostages scheme that became known as the Iran-Contra affair dogged him long after he left the White House.

In 1986, during Reagan's second term, the public learned that his administration had authorized secret arms sales to Iran while seeking Iranian aid in freeing American hostages held in Lebanon. As much as $30 million from the arms sales was diverted, in violation of U.S. law, to aid rebels fighting the leftist government of Nicaragua.

Reagan's national security adviser, John Poindexter, resigned and an aide, Lt. Col. Oliver North, was fired. Both were also convicted of crimes stemming from efforts to deceive and obstruct Congress. Their convictions were later overturned. President George H.W. Bush, Reagan's successor, pardoned six others involved.

Reagan insisted money from the arms sales was funneled to the Nicaraguan Contra rebels without his knowledge.

AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File

Reagan never faced impeachment or court charges for the biggest scandal of his presidency. But the arms-for-hostages scheme that became known as the Iran-Contra affair dogged him long after he left the White House.

In 1986, during Reagan's second term, the public learned that his administration had authorized secret arms sales to Iran while seeking Iranian aid in freeing American hostages held in Lebanon. As much as $30 million from the arms sales was diverted, in violation of U.S. law, to aid rebels fighting the leftist government of Nicaragua.

Reagan's national security adviser, John Poindexter, resigned and an aide, Lt. Col. Oliver North, was fired. Both were also convicted of crimes stemming from efforts to deceive and obstruct Congress. Their convictions were later overturned. President George H.W. Bush, Reagan's successor, pardoned six others involved.

Reagan insisted money from the arms sales was funneled to the Nicaraguan Contra rebels without his knowledge.

-

-

Among 160 years of presidential scandals, Trump stands alone

AP Photo/File

Nixon resigned from office in August 1974 rather than face impeachment for his administration's cover-up of its involvement in a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington.

The bungled burglary at the Watergate office building resulted in the indictment of seven men, including two former White House aides. Five of the Watergate defendants pleaded guilty; two were convicted in criminal trials.

Intrigue over the 1972 Watergate break-in didn't stop Nixon from cruising to reelection a few months later. He endured the storm until the House Judiciary Committee in 1974 approved three articles of impeachment accusing him of obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress.

Before the full House could vote, a bombshell tape recording was released in which Nixon could be heard approving a plan to pressure the FBI to drop its Watergate investigation. Nixon resigned after losing support from key congressional Republicans.

His vice president, Gerald Ford, became president and pardoned Nixon a month later.

AP Photo/File

Nixon resigned from office in August 1974 rather than face impeachment for his administration's cover-up of its involvement in a break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington.

The bungled burglary at the Watergate office building resulted in the indictment of seven men, including two former White House aides. Five of the Watergate defendants pleaded guilty; two were convicted in criminal trials.

Intrigue over the 1972 Watergate break-in didn't stop Nixon from cruising to reelection a few months later. He endured the storm until the House Judiciary Committee in 1974 approved three articles of impeachment accusing him of obstruction of justice, abuse of power and contempt of Congress.

Before the full House could vote, a bombshell tape recording was released in which Nixon could be heard approving a plan to pressure the FBI to drop its Watergate investigation. Nixon resigned after losing support from key congressional Republicans.

His vice president, Gerald Ford, became president and pardoned Nixon a month later.

-

Among 160 years of presidential scandals, Trump stands alone

AP Photo/Mathew Brady, File

While never personally charged with crimes or formally accused of wrongdoing, Grant as president torpedoed a corruption case prosecuted by his own administration. The man on trial was Grant's personal secretary in the White House.

In 1875, an investigation launched by Treasury Secretary Benjamin H. Bristow resulted in hundreds of arrests in a scheme known as the Whiskey Ring, in which distillers, revenue agents and fellow conspirators diverted millions of dollars in liquor taxes to themselves.

The Civil War general-turned-president found himself at odds with the crackdown when Gen. Orville E. Babcock ended up charged as a conspirator. Not only was Babcock the president's personal secretary, but he and Grant had also been friends since the war.

Prosecutors said they had uncovered telegrams Babcock sent to ringleaders to assist their scheme. Regardless, Grant insisted on testifying in his aide's defense.

To avoid the spectacle of the president appearing at Babcock's trial, attorneys questioned Grant under oath at the White House on Feb. 12, 1876. A transcript of his testimony was later read in court in St. Louis. The jury acquitted Babcock, a decision largely credited to Grant's unwavering defense.

AP Photo/Mathew Brady, File

While never personally charged with crimes or formally accused of wrongdoing, Grant as president torpedoed a corruption case prosecuted by his own administration. The man on trial was Grant's personal secretary in the White House.

In 1875, an investigation launched by Treasury Secretary Benjamin H. Bristow resulted in hundreds of arrests in a scheme known as the Whiskey Ring, in which distillers, revenue agents and fellow conspirators diverted millions of dollars in liquor taxes to themselves.

The Civil War general-turned-president found himself at odds with the crackdown when Gen. Orville E. Babcock ended up charged as a conspirator. Not only was Babcock the president's personal secretary, but he and Grant had also been friends since the war.

Prosecutors said they had uncovered telegrams Babcock sent to ringleaders to assist their scheme. Regardless, Grant insisted on testifying in his aide's defense.

To avoid the spectacle of the president appearing at Babcock's trial, attorneys questioned Grant under oath at the White House on Feb. 12, 1876. A transcript of his testimony was later read in court in St. Louis. The jury acquitted Babcock, a decision largely credited to Grant's unwavering defense.

-

-

Among 160 years of presidential scandals, Trump stands alone

Brady-Handy photograph collection/Library of Congress via AP

The first American president to have his legacy tarnished by impeachment, Andrew Johnson's woes arose from his intense feuding with Congress over Reconstruction following the Civil War.

The Tennessee Democrat had been elected vice president in 1864 as part of a unity ticket with Abraham Lincoln, and Johnson assumed the presidency after Lincoln's 1865 assassination. From the White House, Johnson called for pardoning Confederate leaders and opposed extending voting rights to freed Blacks, infuriating congressional Republicans.

It was Johnson's firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Lincoln appointee who favored tougher policies toward the defeated South, that prompted the House to pass articles of impeachment that accused the president of ousting and replacing Stanton illegally.

Johnson's impeachment trial began in the Senate on March 5, 1868. It ended more than two months later, with senators just one vote short of removing Johnson from office. He served the remainder of his final year, but fellow Democrats denied him their nomination to run again.

Brady-Handy photograph collection/Library of Congress via AP

The first American president to have his legacy tarnished by impeachment, Andrew Johnson's woes arose from his intense feuding with Congress over Reconstruction following the Civil War.

The Tennessee Democrat had been elected vice president in 1864 as part of a unity ticket with Abraham Lincoln, and Johnson assumed the presidency after Lincoln's 1865 assassination. From the White House, Johnson called for pardoning Confederate leaders and opposed extending voting rights to freed Blacks, infuriating congressional Republicans.

It was Johnson's firing of Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Lincoln appointee who favored tougher policies toward the defeated South, that prompted the House to pass articles of impeachment that accused the president of ousting and replacing Stanton illegally.

Johnson's impeachment trial began in the Senate on March 5, 1868. It ended more than two months later, with senators just one vote short of removing Johnson from office. He served the remainder of his final year, but fellow Democrats denied him their nomination to run again.