NEW YORK (AP) — Less than six months ago, mpox was an exploding health crisis. What had been an obscure disease from Africa was ripping through European and U.S. gay communities. Precious doses of an unproven vaccine were in short supply. International officials declared health emergencies.

Today, reports of new cases are down to a trickle in the U.S. Health officials are shutting down emergency mobilizations. The threat seems to have virtually disappeared from the public consciousness.

“We’re in a remarkably different place,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a Vanderbilt University infectious diseases expert. “It’s really impressive how that peak has come down to very, very low levels.”

So who deserves the credit? It’s an unsettled question, but experts cite a combination of factors.

Some commend public health officials. Others say more of the credit should go to members of the gay and bisexual community who took their own steps to reduce disease spread when the threat became clear. Some wonder if characteristics of the virus itself played a role.

“It’s a mixed story” in which some things could have gone better but others went well, said Dr. Tom Frieden, a former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

***

AP Photo/Mary Altaffer, File

FILE - A physician assistant prepares a syringe with the Mpox vaccine for a patient at a vaccination clinic in New York on Friday, Aug. 19, 2022. Mpox is no longer the exploding health crisis that it appeared to be less than six months ago.

Cases soar, then fall

Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox, is a rare disease caused by infection with a virus that’s in the same family as the one that causes smallpox. It is endemic in parts of Africa, where people have been infected through bites from rodents or small animals, but it was not known to spread easily among people.

Mpox cases began emerging in Europe and the U.S. in May, mostly among men who have sex with men. Cases escalated rapidly in dozens of countries in June and July, around the time of gay pride events. The infections were rarely fatal, but many people suffered painful skin lesions for weeks.

In late July, the World Health Organization declared an international health crisis. In early August, the U.S. declared a public health emergency.

Soon after, the outbreak began diminishing. The daily average of newly reported U.S. cases went from nearly 500 in August to about 100 in October. Now, there are fewer than five new U.S. cases per day. (Europe has seen a similar drop.)

Experts said a combination of factors likely turned the tide.

***

AP Photo/Jeenah Moon, File

FILE - Vials of single doses of the Jynneos vaccine for mpox are seen from a cooler at a vaccinations site on Aug. 29, 2022, in the Brooklyn borough of New York.

Vaccinations

Health officials caught an early break: An existing two-dose vaccine named Jynneos, developed to fight smallpox, was also approved for use against the monkeypox.

Initially, only a few thousand doses were available in the U.S., and most countries had none at all. Shipping and regulatory delays left local health departments unable to meet demand for shots.

In early August, U.S. health officials decided to stretch the limited supply by giving people just one-fifth the usual dose. The plan called for administering the vaccine with an injection just under the skin, rather than into deeper tissue.

Some in the public health community worried that it was a big decision based on a small amount of research — a single 2015 study. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention since then has confirmed there was no difference in vaccine performance between the two methods.

“They got criticized for the revised dosing strategy, but it was the right call,” said Frieden, who is currently president of Resolve to Save Lives, a non-profit organization focused on preventing epidemics.

Cases, however, had already begun falling by the time the government made the switch.

***

AP Photo/Cliff Owen, File

FILE - Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, testifies during the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions hearing to examine stopping the spread of mpox, focusing on the federal response, in Washington, Wednesday, Sept. 14, 2022.

Community outreach

The current CDC director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, cited efforts to educate doctors on how to better diagnose and treat mpox. Other experts said that even more important was outreach to the sexually active gay and bisexual men most at risk.

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

Naming diseases is a complicated business. To be useful, a name needs to be unique, descriptive, and memorable so it can be referenced easily, especially when medical situations become urgent. Though the easiest way to name illnesses may be just to give them identification numbers, that system becomes extraordinarily difficult to reference efficiently when time is of the essence.

It may seem intuitive to name diseases based on their origins or discovery locations; however, this approach also presents issues. As our world increasingly boasts a global citizenry, illnesses—and their names—can be spread across various cultures, making it essential to be sensitive to and inclusive of all who may encounter them.

In light of recent conversations about disease nomenclature, Stacker investigated how "monkeypox" and other disease names have caused controversy, using a collection of news, scientific, and government sources. While this is not an all-inclusive list of the issues surrounding the naming of diseases, it explores several fraught means by which illnesses are given nomenclature that becomes shorthand for public discussion.

You may also like: Fastest-warming states since 1970

Canva

Naming diseases is a complicated business. To be useful, a name needs to be unique, descriptive, and memorable so it can be referenced easily, especially when medical situations become urgent. Though the easiest way to name illnesses may be just to give them identification numbers, that system becomes extraordinarily difficult to reference efficiently when time is of the essence.

It may seem intuitive to name diseases based on their origins or discovery locations; however, this approach also presents issues. As our world increasingly boasts a global citizenry, illnesses—and their names—can be spread across various cultures, making it essential to be sensitive to and inclusive of all who may encounter them.

In light of recent conversations about disease nomenclature, Stacker investigated how "monkeypox" and other disease names have caused controversy, using a collection of news, scientific, and government sources. While this is not an all-inclusive list of the issues surrounding the naming of diseases, it explores several fraught means by which illnesses are given nomenclature that becomes shorthand for public discussion.

You may also like: Fastest-warming states since 1970

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

Naming illnesses based on where they were presumed to have originated was a common practice for decades. The "Spanish flu" from the early 1900s is just one of many toponymous diseases that earned its name based on a physical place. However, in 2015, the World Health Organization released new guidelines that advised against this practice. When an illness becomes irrevocably tied to a place, people from that place often face discrimination or violence—even if the illness is later proven to have come from someplace different.

One recent example of a toponymous disease causing backlash occurred at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when some people, including then-President Donald Trump, referred to the novel coronavirus as the "Wuhan flu" or the "Chinese virus." Many experts and medical professionals spoke up, stating that the monikers were xenophobic and prompted anti-Asian hate.

Other diseases named after places include the Zika virus, named after the Zika Forest in Uganda; Marburg virus, named after Marburg, Germany, where more than 30 cases of the illness were recorded; and Middle East respiratory syndrome, named after being first found in Saudi Arabia.

Canva

Naming illnesses based on where they were presumed to have originated was a common practice for decades. The "Spanish flu" from the early 1900s is just one of many toponymous diseases that earned its name based on a physical place. However, in 2015, the World Health Organization released new guidelines that advised against this practice. When an illness becomes irrevocably tied to a place, people from that place often face discrimination or violence—even if the illness is later proven to have come from someplace different.

One recent example of a toponymous disease causing backlash occurred at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when some people, including then-President Donald Trump, referred to the novel coronavirus as the "Wuhan flu" or the "Chinese virus." Many experts and medical professionals spoke up, stating that the monikers were xenophobic and prompted anti-Asian hate.

Other diseases named after places include the Zika virus, named after the Zika Forest in Uganda; Marburg virus, named after Marburg, Germany, where more than 30 cases of the illness were recorded; and Middle East respiratory syndrome, named after being first found in Saudi Arabia.

-

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

The list of diseases named after animal species is long and includes monkeypox, swine flu, and mad cow disease, among others. Though it may seem harmless to name an illness using its presumed species of origin or a carrier species, WHO guidelines also warn against this practice. In the wake of swine flu (also known as H1N1) outbreaks in other countries in 2009, Egypt ordered the slaughter of all pig livestock in the country despite not having any cases, resulting in the killing of about 300,000 animals.

Most recently, the name "monkeypox" has incited people to attack primates in zoos and their natural habitats out of fear of contracting the virus. WHO officials have attempted to redirect disease prevention efforts to focus on human-to-human transmission, but the prevalence of the "monkeypox" name isn't helping the cause. In addition, 29 experts wrote an article in August 2022 calling for the term "monkeypox" to be changed due to its racist connotations against Black people and people of African descent.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

Canva

The list of diseases named after animal species is long and includes monkeypox, swine flu, and mad cow disease, among others. Though it may seem harmless to name an illness using its presumed species of origin or a carrier species, WHO guidelines also warn against this practice. In the wake of swine flu (also known as H1N1) outbreaks in other countries in 2009, Egypt ordered the slaughter of all pig livestock in the country despite not having any cases, resulting in the killing of about 300,000 animals.

Most recently, the name "monkeypox" has incited people to attack primates in zoos and their natural habitats out of fear of contracting the virus. WHO officials have attempted to redirect disease prevention efforts to focus on human-to-human transmission, but the prevalence of the "monkeypox" name isn't helping the cause. In addition, 29 experts wrote an article in August 2022 calling for the term "monkeypox" to be changed due to its racist connotations against Black people and people of African descent.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Votava/brandstaetter images via Getty Images

It's not unusual for scientists to name their discoveries after themselves: Halley's Comet, Verreaux's sifaka, and Avogadro's number are just a few examples. But when it comes to physical illnesses, the politics of having an individual's name in the disease name becomes tricky. One such disease the WHO specifically named in its updated naming guidance is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, first described by neurologists Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Maria Jakob but named by a third neurologist, Walther Spielmeyer.

Names in this category are discouraged because they are not descriptive; however, the situation can be further complicated when the condition is named after a controversial figure. This is the case for Asperger's syndrome, which is no longer an official diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association as of 2013. Hans Asperger was a Nazi scientist during the Second World War and was responsible for the deaths of dozens of children; however, his dark story was not revealed publicly for many years after the diagnosis became common. The physical and mental conditions initially associated with Asperger's syndrome are now classified under the diagnosis of autism. However, laypeople still use the name despite its removal from official medical practices.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

Votava/brandstaetter images via Getty Images

It's not unusual for scientists to name their discoveries after themselves: Halley's Comet, Verreaux's sifaka, and Avogadro's number are just a few examples. But when it comes to physical illnesses, the politics of having an individual's name in the disease name becomes tricky. One such disease the WHO specifically named in its updated naming guidance is Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, first described by neurologists Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt and Alfons Maria Jakob but named by a third neurologist, Walther Spielmeyer.

Names in this category are discouraged because they are not descriptive; however, the situation can be further complicated when the condition is named after a controversial figure. This is the case for Asperger's syndrome, which is no longer an official diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association as of 2013. Hans Asperger was a Nazi scientist during the Second World War and was responsible for the deaths of dozens of children; however, his dark story was not revealed publicly for many years after the diagnosis became common. The physical and mental conditions initially associated with Asperger's syndrome are now classified under the diagnosis of autism. However, laypeople still use the name despite its removal from official medical practices.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

-

-

As STDs proliferate, companies tout at-home test kits. Are they reliable?

Canva

At the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and before the virus had been studied in-depth, it was called "gay-related immunodeficiency" because of its prevalence among homosexual men. At the time, it was assumed that sexual orientation had to be a causal agent of the disease. Though it is now known that HIV is not caused by sexual orientation but is transmitted by sexual contact or contact with infected blood, homophobia still lingers around the disease, serving as a warning for future disease names to mitigate discrimination caused by nomenclature.

Beyond HIV, controversy ensued during outbreaks of H1N1, or swine flu, in Israel. Because Israel has large Jewish and Muslim populations, many of its citizens took offense to the reference to pigs in the flu's name because pigs are neither kosher nor halal. As a result, Israel's deputy health minister announced that the illness would instead be called "Mexican flu," based on the finding that the first human H1N1 patient was Mexican. This caused the Mexican ambassador to Israel to launch an official complaint against the Israeli government, ultimately resulting in Israel's acceptance of the term "swine flu" after all.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

Canva

At the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and before the virus had been studied in-depth, it was called "gay-related immunodeficiency" because of its prevalence among homosexual men. At the time, it was assumed that sexual orientation had to be a causal agent of the disease. Though it is now known that HIV is not caused by sexual orientation but is transmitted by sexual contact or contact with infected blood, homophobia still lingers around the disease, serving as a warning for future disease names to mitigate discrimination caused by nomenclature.

Beyond HIV, controversy ensued during outbreaks of H1N1, or swine flu, in Israel. Because Israel has large Jewish and Muslim populations, many of its citizens took offense to the reference to pigs in the flu's name because pigs are neither kosher nor halal. As a result, Israel's deputy health minister announced that the illness would instead be called "Mexican flu," based on the finding that the first human H1N1 patient was Mexican. This caused the Mexican ambassador to Israel to launch an official complaint against the Israeli government, ultimately resulting in Israel's acceptance of the term "swine flu" after all.

You may also like: Animal species that may become extinct in our lifetime

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Mary Altaffer

Healthcare workers with New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene help people register for the monkeypox vaccine at one of the City's vaccination sites, Tuesday, July 26, 2022, in New York. The World Health Organization recently declared that the expanding monkeypox outbreak is a global emergency. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

Mary Altaffer

Healthcare workers with New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene help people register for the monkeypox vaccine at one of the City's vaccination sites, Tuesday, July 26, 2022, in New York. The World Health Organization recently declared that the expanding monkeypox outbreak is a global emergency. (AP Photo/Mary Altaffer)

-

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Marcio Jose Sanchez

People line up at a monkeypox vaccination site Thursday, July 28, 2022, in Encino, Calif. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez)

Marcio Jose Sanchez

People line up at a monkeypox vaccination site Thursday, July 28, 2022, in Encino, Calif. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez)

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Eric Risberg

Tom Temprano poses in the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, Thursday, July 28, 2022. Temprano was scheduled to get his second dose of the Monkeypox vaccine next week but was just notified that it is canceled because of short supply. He is frustrated that authorities have taken so long to respond, and noted they did so after LGBTQ politicians in his community raised their voices.(AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Eric Risberg

Tom Temprano poses in the Castro neighborhood of San Francisco, Thursday, July 28, 2022. Temprano was scheduled to get his second dose of the Monkeypox vaccine next week but was just notified that it is canceled because of short supply. He is frustrated that authorities have taken so long to respond, and noted they did so after LGBTQ politicians in his community raised their voices.(AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

-

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Francisco Seco

FILE - Daniel Rofin, 41, receives a vaccine against Monkeypox from a health professional in medical center in Barcelona, Spain, July 26, 2022. The U.S. will declare a public health emergency to bolster the federal response to the outbreak of monkeypox that already has infected more than 6,600 Americans. That's according to two people familiar with the matter said. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco, File)

Francisco Seco

FILE - Daniel Rofin, 41, receives a vaccine against Monkeypox from a health professional in medical center in Barcelona, Spain, July 26, 2022. The U.S. will declare a public health emergency to bolster the federal response to the outbreak of monkeypox that already has infected more than 6,600 Americans. That's according to two people familiar with the matter said. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco, File)

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Haven Daley

FILE - A sign urges the release of the monkeypox vaccine during a protest in San Francisco, July 18, 2022. The mayor of San Francisco announced a legal state of emergency Thursday, July 28, 2022, over the growing number of monkeypox cases. Public health officials warn that moves by rich countries to buy large quantities of monkeypox vaccine, while declining to share doses with Africa, could leave millions of people unprotected against a more dangerous version of the disease and risk continued spillovers of the virus into humans. (AP Photo/Haven Daley, File)

Haven Daley

FILE - A sign urges the release of the monkeypox vaccine during a protest in San Francisco, July 18, 2022. The mayor of San Francisco announced a legal state of emergency Thursday, July 28, 2022, over the growing number of monkeypox cases. Public health officials warn that moves by rich countries to buy large quantities of monkeypox vaccine, while declining to share doses with Africa, could leave millions of people unprotected against a more dangerous version of the disease and risk continued spillovers of the virus into humans. (AP Photo/Haven Daley, File)

-

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Marcio Jose Sanchez

FILE - People line up at a monkeypox vaccination site on Thursday, July 28, 2022, in Encino, Calif. California's public health officer said they are pressing for more vaccine and closely monitoring the spread of the monkeypox virus. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File)

Marcio Jose Sanchez

FILE - People line up at a monkeypox vaccination site on Thursday, July 28, 2022, in Encino, Calif. California's public health officer said they are pressing for more vaccine and closely monitoring the spread of the monkeypox virus. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File)

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Rick Bowmer

Micro-biologist Annette Atkinson adjusts her power air purifying respirator during a demonstration how the monkeypox is tested for at the Utah Public Health Laboratory Friday, July 29, 2022, in Taylorsville, Utah. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

Rick Bowmer

Micro-biologist Annette Atkinson adjusts her power air purifying respirator during a demonstration how the monkeypox is tested for at the Utah Public Health Laboratory Friday, July 29, 2022, in Taylorsville, Utah. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer)

-

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Marcio Jose Sanchez

FILE - People line up at a monkeypox vaccination site, Thursday, July 28, 2022, in Encino, Calif. California's governor declared a state of emergency over monkeypox, becoming the second state in three days to take the step. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File)

Marcio Jose Sanchez

FILE - People line up at a monkeypox vaccination site, Thursday, July 28, 2022, in Encino, Calif. California's governor declared a state of emergency over monkeypox, becoming the second state in three days to take the step. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez, File)

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Haven Daley

FILE - A man holds a sign urging increased access to the monkeypox vaccine during a protest in San Francisco, July 18, 2022. California's governor on Monday, Aug. 1, 2022, declared a state of emergency to speed efforts to combat the monkeypox outbreak, becoming the second state in three days to take the step. (AP Photo/Haven Daley, File)

Haven Daley

FILE - A man holds a sign urging increased access to the monkeypox vaccine during a protest in San Francisco, July 18, 2022. California's governor on Monday, Aug. 1, 2022, declared a state of emergency to speed efforts to combat the monkeypox outbreak, becoming the second state in three days to take the step. (AP Photo/Haven Daley, File)

-

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Richard Vogel

Scott Marszalek receives a Monkeypox vaccination at a Pop-Up Monkeypox vaccination site at the West Hollywood Library Community Meeting Room on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. The City of West Hollywood is working with public health officials at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health in responding to the monkeypox outbreak. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

Richard Vogel

Scott Marszalek receives a Monkeypox vaccination at a Pop-Up Monkeypox vaccination site at the West Hollywood Library Community Meeting Room on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. The City of West Hollywood is working with public health officials at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health in responding to the monkeypox outbreak. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Richard Vogel

People arrive to check in at a Monkeypox Vaccination Pop-Up Site on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

Richard Vogel

People arrive to check in at a Monkeypox Vaccination Pop-Up Site on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

-

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Richard Vogel

A patient receives a Monkeypox vaccination at a Pop-Up vaccination site at the West Hollywood Library community meeting room on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

Richard Vogel

A patient receives a Monkeypox vaccination at a Pop-Up vaccination site at the West Hollywood Library community meeting room on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Richard Vogel

USC pharmacy intern Gizelle Mendoza, loads a syringe with Monkeypox vaccine at a Pop-Up Monkeypox vaccination site on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

Richard Vogel

USC pharmacy intern Gizelle Mendoza, loads a syringe with Monkeypox vaccine at a Pop-Up Monkeypox vaccination site on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

-

-

MPX? Mpox? The struggle to replace ‘monkeypox’ with a name that isn’t racist

Richard Vogel

Dr. Andrea Kim, Director of Vaccine Preventable Disease Control talks to the media at a Pop-Up Monkeypox vaccination site on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

Richard Vogel

Dr. Andrea Kim, Director of Vaccine Preventable Disease Control talks to the media at a Pop-Up Monkeypox vaccination site on Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in West Hollywood, Calif. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

In the first months of the outbreak, the government was cautious about focusing warnings too intently on gay and bisexual men for fear of stigmatizing the men and — in so doing — undermining efforts to identify infections. (Indeed, in November the WHO changed the name of the disease from monkeypox to mpox in an effort to reduce stigma.)

“They were a little coy about the population principally affected,” Schaffner said.

Many say queer activists and community organizations stepped up to fill the void, quickly offering frank education and assistance. In an online survey conducted in early August, many men who have sex with men reported having fewer sexual encounters and partners because of the outbreak.

“The success was really due to grassroots activities,” said Amira Roess, a George Mason University professor of epidemiology and global health. Leaders in the gay community “took it upon themselves to step in when the government response was really lacking” in a way that recalled what happened during the plodding government response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, she said.

Among those efforts was called RESPND-MI — Rapid Epidemiologic Study of Prevalence, Networks, and Demographics of Monkeypox Infection. The grant-funded organization put out transmission-prevention messaging, conducted a community-led survey of mpox symptoms, and mapped the social and sexual networks of queer and transgender people in New York City.

Nick Diamond, a leader of the effort, said government response improved only after gay activists pressured officials and did a lot of the outreach and education themselves.

“A lot of HIV activists knew that it would be up to us to start a response to monkeypox,” he said.

But Diamond also noted another possible reason for the declines: Spread of mpox at LGBTQ celebrations in June — coupled with a lack of testing and vaccinations — likely contributed to the July surge. “A lot of people came out of Pride, after being in close contact, symptomatic,” he said. They suffered blisters and scabs, bringing home the message to other at-risk men that the virus was a very real danger.

***

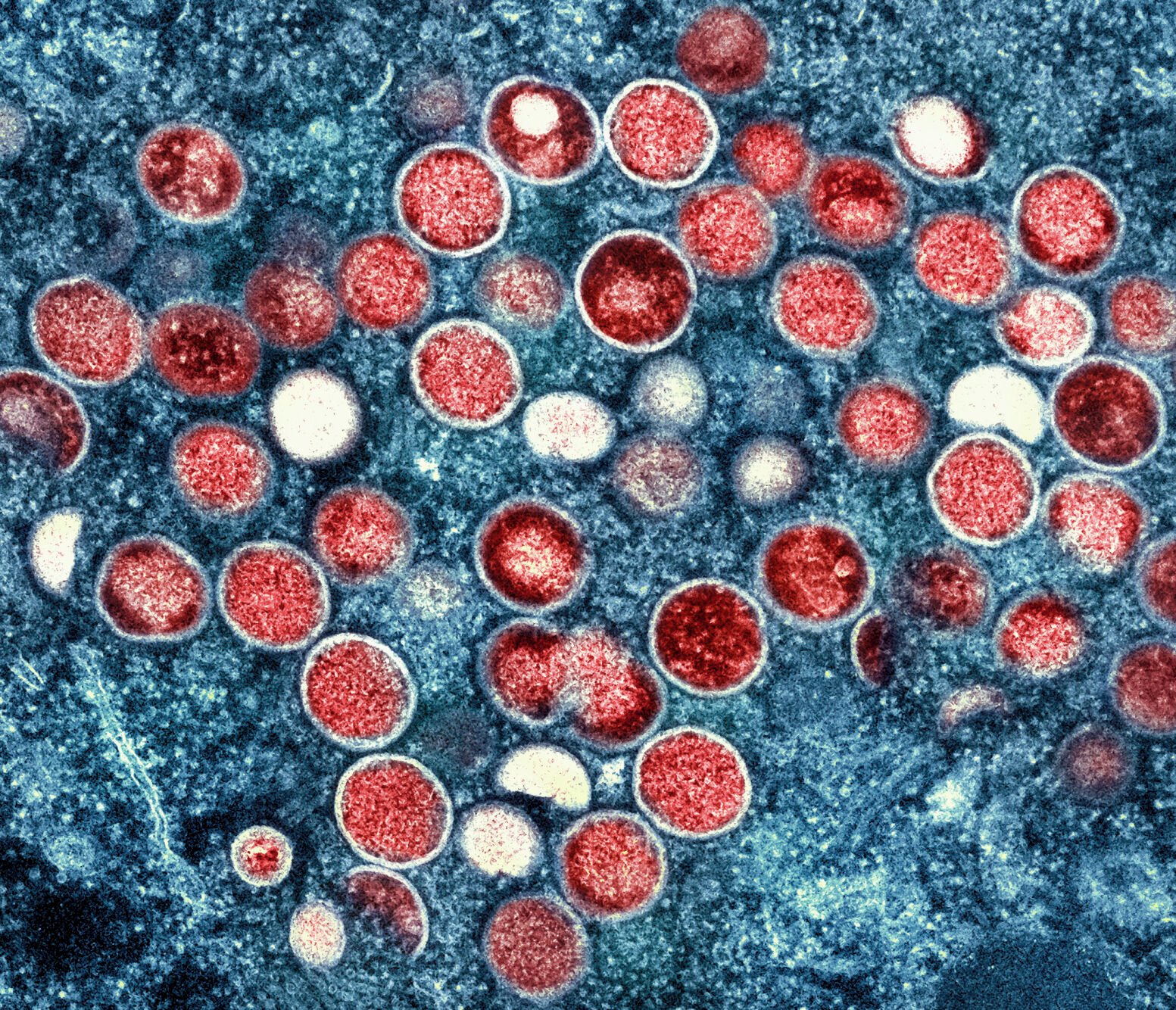

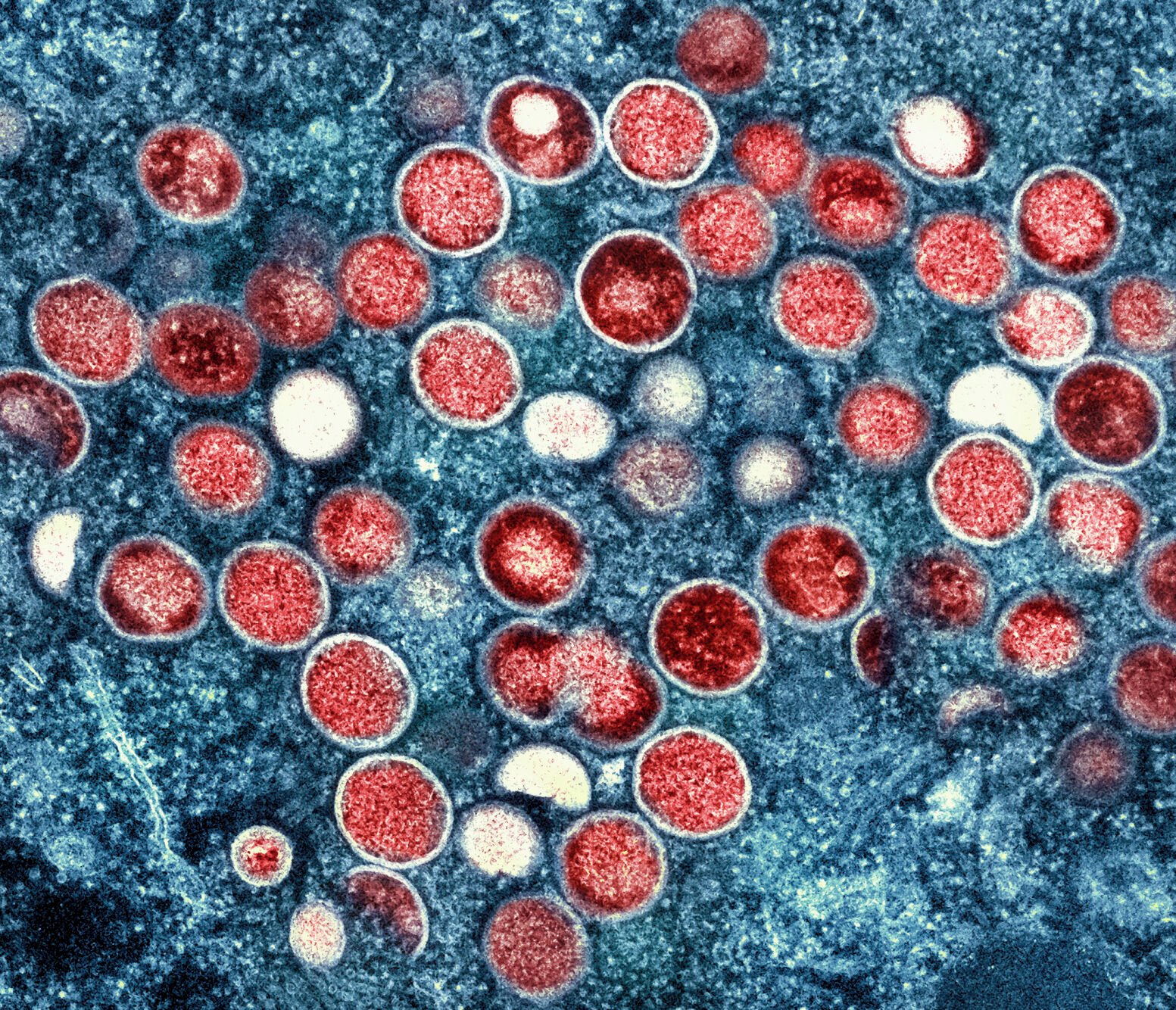

NIAID via AP, File

FILE - This image provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) shows a colorized transmission electron micrograph of mpox particles (red) found within an infected cell (blue), cultured in the laboratory that was captured and color-enhanced at the NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF) in Fort Detrick, Md.

Biology vs. behavior

There are also possible explanations that have more to do with biology than behavior.

The number of new infections may have been limited by increases in infection-acquired immunity in the men active in the social networks that fueled the outbreak, CDC scientists said in a recent report.

Past research has suggested there may be limits in how many times monkeypox virus will spread from person to person, noted Stephen Morse, a Columbia University virologist.

“The monkeypox virus essentially loses steam after a couple of rounds in humans,” Morse said. “Everyone credits the interventions, but I don’t know what the reason really is.”